https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/31/world/asia/theresa-may-china.html

As Theresa May Pursues Deals in China, Her Own Troubles Follow

By CHRIS BUCKLEY and STEPHEN CASTLEJAN. 31, 2018

Continue reading the main story Share This Page

- Share

- Tweet

- More

- Save

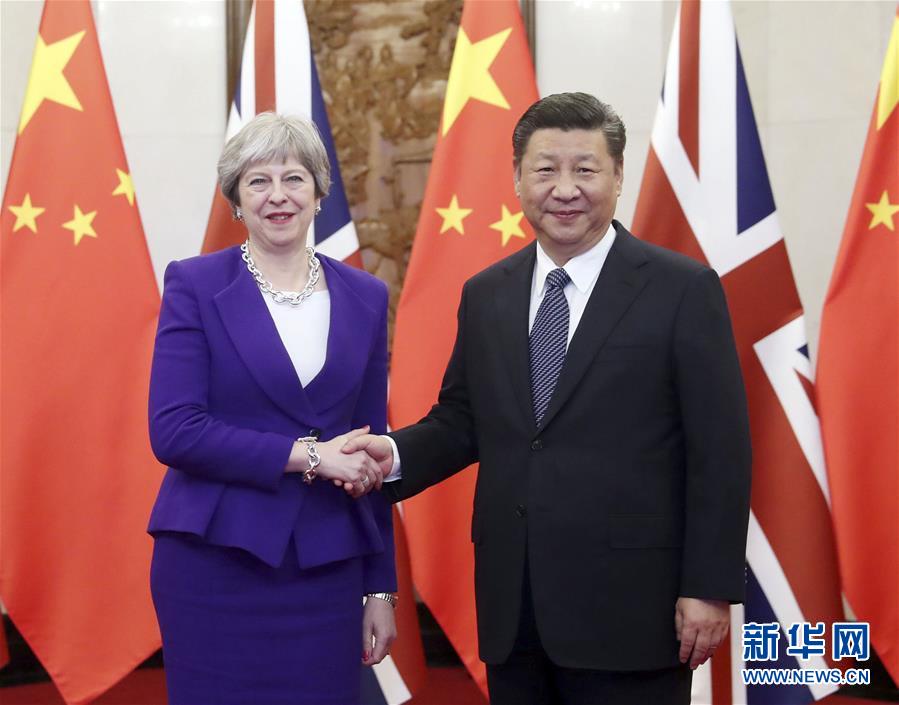

Prime Minister Theresa May of Britain and her husband, Philip May, arriving in Wuhan, China, on Wednesday. Mrs. May’s political troubles and uncertainty over Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union are likely to shadow her three-day China trip. Credit Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

BEIJING — Theresa May on Wednesday joined a succession of British prime ministers who have turned to China for trade, investment and a shot of confidence, while offering Britain as a reliable, competitive base in Europe.

But her three-day trip to China, shadowed by uncertainties about Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union as well as Mrs. May’s hold on power, has the makings of a long march.

Before her arrival on Wednesday, Mrs. May said the trip would “intensify the golden era” in the two countries’ relationship, echoing language that her predecessor, David Cameron, had used to court President Xi Jinping.

In the Great Hall of the People in central Beijing, Mrs. May told China’s premier, Li Keqiang, that they should seek to “build further on that golden era and on the global strategic partnership that we have been working on between the U.K. and China.”

Mr. Li responded with equally effusive rhetoric.

Video by CGTN

But while Chinese leaders seemed unlikely to publicly air any misgivings over Brexit, as Britain’s withdrawal from the bloc is known, or about Mrs. May’s ability to deliver on commitments, experts said such worries would cloud her visit and limit its results.

Continue reading the main story

Related Coverage

As Brexit Agonies Continue, Theresa May Is Under Threat Again JAN. 29, 2018

Theresa May Arrives in Davos as U.K.’s Post-‘Brexit’ Slide Continues JAN. 25, 2018

Theresa May, Navigating Brexit, Reaches a First Finish Line DEC. 14, 2017

Continue reading the main story

“This is the first visit by the British leader since the Brexit referendum, and for both sides the primary aspect is reaffirming the status of that Sino-British ‘golden era,’” said Cui Hongjian, the director of European studies at the China Institute of International Studies, a state institute in Beijing.

“Sino-British trade has felt some impact from Brexit,” Mr. Cui said. “We’ll see whether this time there can be better communication to resolve some problems.”

Mrs. May’s own political fate is also weighing on the visit. On her flight to her first stop in China, Wuhan, an industrial city on the Yangtze River, she was peppered with reporters’ questions about calls for her resignation from within her own Conservative Party.

Photo

Mrs. May with the Chinese actress Maggie Jiang at Wuhan University. Credit Reuters

“I‘m not a quitter and there is a long-term job to be done,” she said, according to Reuters. “That job is about getting the best Brexit deal, about ensuring that we take back control of our money, our laws, our borders, that we can sign trade deals around the rest of the world.”

China, the world’s second-biggest economy, could become a more important source of customers and investment for Britain as its scheduled March 2019 departure from the European Union looms. After her meetings in Beijing, including with Mr. Xi, Mrs. May will visit Shanghai to promote trade and investment.

In 2016, China was the destination for 3.1 percent of British exports of goods and services, while 43 percent went to other European Union member countries. Chinese officials are eager to talk up prospects for more business, and British exports to China have been growing. Representatives of more than 40 companies, universities and trade groups are accompanying Mrs. May on her trip.

In a press appearance with Mr. Li, Mrs. May said that she had won China’s agreement to take steps toward lifting a ban on British beef imports, which dated back to the crisis over mad cow disease during the 1990s.

But China also bristles with policies and practices that protect many domestic industries from foreign competitors, and Mrs. May has sounded a more guarded note about prospects for cooperation than did Mr. Cameron and his Labour Party predecessors, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair.

Mr. Cameron and George Osborne, the former chancellor of the Exchequer, courted Chinese investment aggressively, placing less emphasis on contentious issues like democracy, human rights and the future of Hong Kong, a former British colony. In 2015, Britain also bucked the United States by joining China’s fledgling Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

The Interpreter Newsletter

Understand the world with sharp insight and commentary on the major news stories of the week.

You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

- See Sample

- Privacy Policy

- Opt out or contact us anytime

“It was a very marked shift from the moment she came to power,” said Rosemary Foot, a senior research fellow at the University of Oxford who studies Chinese foreign relations.

Chinese interest in investing in some sectors of the British economy, like infrastructure, technology and even financial services in London, probably will not be seriously dampened by Britain’s departure from the European Union, said Paul C. Irwin Crookes, a senior lecturer at Oxford University who is studying the consequences of Brexit for the countries’ ties.

Photo

Mrs. May at the Wuhan airport with a British business delegation traveling with her. The prime minister has courted Chinese investment less aggressively than her predecessor did. Credit Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

But in other sectors, Chinese companies’ willingness to invest could depend greatly on the terms of Britain’s new relationship with Europe, he said.

In theory, after it leaves the bloc, Britain “could design a relationship with China that could move away from the model currently being put forward in the E.U.-China relationship,” Dr. Irwin Crookes said by email. But in practice, the European Union may demand that Britain avoid policies that undercut European trade positions, he said.

“This then is also a matter of high politics, and it is unclear in what direction it could move,” Dr. Irwin Crookes said.

This is not Mrs. May’s first visit to China; she and Mr. Xi met during the Group of 20 summit meeting in the eastern city of Hangzhou in 2016. But this time, Mrs. May faces the dilemma of whether to endorse Mr. Xi’s “Belt and Road” initiative — his expansive vision of ports, roads, railways and other infrastructure to spread Chinese trade and influence.

That project has unsettled some American and European policymakers, who worry it will be a vehicle for one-sided Chinese influence and interests. Britain has been cautious, but Mr. Xi has made it one of his signature international undertakings. Mrs. May said in Beijing that Britain would work with China on deciding how to cooperate on the initiative, while ensuring that it “meets international standards.”

“Obviously, China knows that Britain is pretty desperate for trade deals, so maybe she’s trying to generate a bit of leverage of her own,” said Dr. Foot of Oxford. “Secondly, there’s a genuine concern that involvement in ‘Belt and Road’ is not going to be open, essentially, to other companies and to other countries.”

Mrs. May has also been pushed to raise what Chris Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, called “increasing threats to basic freedoms” in the city, which Britain returned to China in 1997 under a promise that Beijing would let it keep its civil liberties and legal autonomy for 50 years. Mr. Xi’s government has tightened its grip on Hong Kong politics, publishing and news media, especially since the 2014 protests there over China’s refusal to allow fully democratic elections in the city.

In a letter to Mrs. May this week, Mr. Patten and Paddy Ashdown, former leader of the centrist Liberal Democrats, asked for assurances that Britain’s growing commercial relationship with China would not “come at the cost of our obligations” to the people of Hong Kong.

“It’s been very difficult to build up a broad base of interest in the subtle changes that have been going on in Hong Kong,” Dr. Foot said. “It’s a long time since the handover of 1997, so it’s been very difficult against the weight of China’s economic and political prominence.”

Chris Buckley reported from Beijing, and Stephen Castle from London. Adam Wu contributed research from Beijing.