- Joined

- Aug 20, 2022

- Messages

- 24,803

- Points

- 113

Vietnam to make English a compulsory 2nd language in all schools by 2035, to be more competitive

Published Nov 16, 2025, 05:00 AMUpdated Nov 16, 2025, 11:40 AM

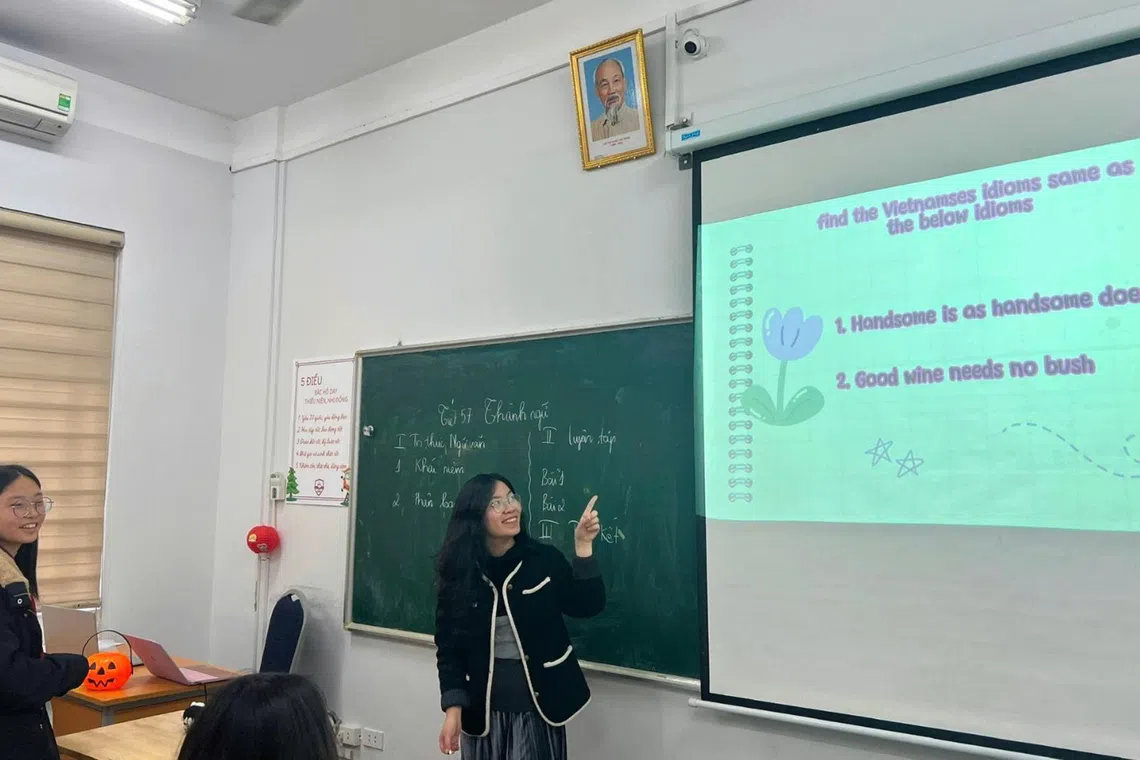

The ambitious plan extends beyond just teaching English as a subject to include teaching other academic subjects in English as well as Vietnamese.

PHOTO: ULIS MIDDLE SCHOOL

Nga Pham

www.straitstimes.com

- “The English language helps me talk to people from different countries,” said 11-year-old Kim Long. “I also love it because I can read lots of books and comics, and watch football on YouTube, too,” he rattled on in fluent English.

The boy – who is in Grade 5 (the equivalent of Primary 5 in Singapore) – and his peers in Nguyen Binh Khiem Elementary School, in Cau Giay, Hanoi, have been learning English since first grade. At school, the pupils have daily English classes. They also take part in games, sing and watch videos in English.

Since 2023, maths and science lessons in the school have been conducted in Vietnamese and English – a school initiative strongly supported by parents.

This primary school is not the norm in Vietnam – at least, not now. But by 2030, the government hopes, every child will have the opportunity to learn English from the age of six, as Long did.

Currently, English is mandatory only from Grade 3. Some schools with enough qualified teachers and facilities can offer it from Grade 1, but only as an elective with two lessons a week.

Recently, the Vietnamese government announced a nationwide plan to establish English as a compulsory second language in all schools by 2035, and a mandatory subject from Grade 1 by 2030. In addition, under the new initiative, all kindergartens and pre-schools must introduce children to English within the next five years.

Nguyen Binh Khiem’s vice-principal Pham Thi Bich Ngoc told The Straits Times that the school has incorporated the English language into its first-grade curriculum for the past five years.

“Currently, although English is still an elective subject in Grades 1 and 2, the school has built an integrated English programme to help students become familiar with the language naturally from the very beginning,” said Ms Ngoc. “Our goal is to develop communication reflexes, confident listening and speaking skills, and a love of learning English in young children.”

In Vietnam, more than 90 per cent of students attend government or public schools.

Primary or elementary schools have pupils from Grades 1 to 5. Middle school is for Grades 6 to 9, and high school for Grades 10 to 12, and then students may head on to university.

There are a handful of private schools catering to Vietnamese students, and around 80 international schools – mostly in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City – with the medium of instruction in languages such as English, French and Russian, which serve mainly the foreign community.

The plan is to improve English proficiency and help “shape a globally competent generation ready for international integration”, according to a government statement in late October.

By 2045, English is expected to be widely used in 50,000 public schools with nearly 30 million students across the country. At present, there are more than 26,000 schools in Vietnam with some 23 million students.

Mrs Le Huong Lan, 28, an office manager in Hanoi, said that although her four-year-old daughter has yet to start formal schooling, she is keen for her to learn English as soon as possible.

“English is as important as Vietnamese these days, because our children will be global citizens when they grow up.”

In order to achieve this “extremely ambitious” plan, noted Mr Bui Manh Hung, 62, former chief coordinator of Vietnam’s general education reform, the education system needs to overcome various challenges. These include an acute shortage of English language teachers and the kind of teaching that focuses on passing exams instead of effective communication.

“A second language is a language that is not the mother tongue but is widely used in the society where the learners live, not only in schools but also in work and daily communication. That language must be used for real communication, and not just learnt in the classroom,” he told ST. Mr Hung remains active in the education sector as a lecturer and adviser to schools, universities and government committees.

However, it would be “unrealistic” to expect the Vietnamese to adopt the English language as it has been done in Singapore, the Philippines or India, due to historical circumstances, he said.

“It will always be regarded as a foreign language – not a national language, but a very special, top-priority foreign language,” he added.

Vietnam’s Ministry of Education and Training estimates that by 2030, the country will need an additional 22,000 English teachers in the pre-school and elementary system. The country currently has 1.05 million pre-school and general education teachers of all grades, of whom only around 30,000 specialise in English.

Each year, the country’s universities and teacher training institutes produce about 3,000 teachers who are proficient and able to teach English, estimates Mr Hung.

Grade 5 pupil Kim Long and his peers in Nguyen Binh Khiem Elementary School, in Cau Giay, Hanoi, have been learning English since the first grade.

PHOTO: TRANG PHAM

“The quality of English teaching in Vietnam is very problematic,” said Ms Tran Thi Thu Trang, 33, an English language schoolteacher in Thai Nguyen province, north-east of Hanoi.

“A large number of teachers are older and their own command of English is not great. Therefore, teaching focuses on grammar and exams, rather than communication.”

During the 1970s and 1980s, Russian was Vietnam’s most popular foreign language, but as the country opened to the world, English took the lead, followed by French and Japanese, according to the Ministry of Education and Training.

Many Russian language teachers retrained and switched to teaching English, even though they did not speak it. One of them, who declined to be named, said she did so to meet the huge demand for English language teachers.

“Officials believed that all foreign languages shared certain similarities, so it was best to make use of our existing teaching skills,” said the trilingual teacher, who is in her 50s.

First-graders during an English-speaking class at Nguyen Binh Khiem Elementary School.

PHOTO: NGUYEN BINH KHIEM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Producing tens of thousands of English language teachers within five years is “almost impossible”, said Mr Hung, the education expert.

“And we’re not even talking about other teaching posts for subjects like maths, information technology and natural sciences... to be conducted in English.”

Yet other educators are hopeful.

“The shift to a bilingual environment requires teachers to not only be good at English, but also be flexible, confident and have appropriate teaching methods,” said Mrs Nguyen Huyen Trang, principal of ULIS Middle School, which is affiliated with the University of Languages and International Studies.

The ambitious plan extends beyond just teaching English as a subject to include teaching other academic subjects in English as well as Vietnamese.

“However, I believe that if there is a continuous training policy and a synchronous support mechanism, this is a feasible transition,” Mrs Trang told ST.

“All the activities at our school, from teaching to extracurricular activities, are aimed at creating a natural English environment for students.”

A bilingual biology class conduced in English and Vietnamese at ULIS Middle School.

PHOTO: ULIS MIDDLE SCHOOL

Vietnamese parents recognise the importance of learning English for their children’s future and investing heavily in English courses at private language schools, which have sprung up in the past decade or two.

English language teaching has become a profitable business, with a three-month learning course for children costing up to 20 million dong (S$985). This, in a country with annual gross domestic product per capita of US$4,700 (S$6,100).

There are about 70 language centres across the country, employing more than 700 qualified foreign teachers, according to unofficial sources. Yet the real number of foreigners who work as English teachers in Vietnam could run well into the thousands.

“The conditions for qualified expat teachers in Vietnam are much better than in neighbouring countries like Thailand or Cambodia,” said Ms Dunuan Kim, 35, from the Philippines.

Ms Kim has been teaching English in a language school in Hanoi for more than three years, earning double what she was offered at a similar school in Bangkok.

“But many unqualified expats work for much less, and the authorities need to act, as this affects education quality,” she said, referring to foreigners living in Vietnam who conduct English lessons even though they are not qualified to do so.

Nguyen Binh Khiem Elementary School pupils practising English in groups.

PHOTO: NGUYEN BINH KHIEM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

The government in 2021 tightened requirements for foreign teachers and language schools, making hiring more difficult – and created challenges for schools with limited resources.

“New regulations require at least three years of experience teaching English as a foreign language, but if you have that experience, you wouldn’t want to live and work in a small town like ours,” said Mrs Thuy Quynh, who runs a language centre in Ninh Binh, 100km from Hanoi.

She said native speakers are crucial for a natural speaking environment, and without them, children in rural areas miss out on opportunities to practise English.

“Most of my students have never had a chance to speak to a foreign teacher,” said Ms Trang, the schoolteacher, who urged the government to invest more resources and more evenly.

Vice-Minister of Education and Training Pham Ngoc Thuong said at a meeting with educators earlier in November that Hanoi’s key priorities include effective resource allocation, teacher training, international partnerships, infrastructure investment and active social engagement. He also underlined the role of digital transformation and technology application, especially the use of artificial intelligence, in English language teaching.

But some industry experts expressed doubts over the ambitious timeline proposed by planners.

“The goal of making English a second language at all schools across the country within the next 10 years, in my opinion, remains far-fetched without concrete measures,” said Mr Hung.

“We need to view this as a long-term strategy rather than just a political decision, and adapt the plan to fit Vietnam’s realities,” he added, implying that the process may need to slow down a little.

However, slowing down is something many in Vietnam’s official circles are reluctant to accept.

Officials say making English a compulsory second language will enhance not only individual career prospects, but the country’s global competitiveness as well. With a workforce proficient in English, Vietnam could become a more attractive destination for international companies – particularly those in the technology and finance sectors, which are core components of the country’s national economic development strategy.

For youngsters like Long, speaking English is the key to turning his childhood dream of becoming a successful footballer-cum-airline pilot into reality.

“I watch YouTube videos (in English) to learn football skills from international players and I need to understand everything they say,” Long said.

“Oh, and it’s football, not soccer (in this part of the world),” he added with a grin.