Singapore — the richest city with the most to lose

Even as Singapore claims its place among the world’s wealthiest cities, a closer look reveals the uncomfortable cost of that ascent.

By

Zat Astha / 24 Jul 2025

Opinion

Singapore is a city obsessed with metrics. Every few months, a new report — sometimes from a bank, sometimes from a consultancy, sometimes from the machinery of state itself — places Singapore somewhere near the top.

Safest city. Most liveable city. Smartest city. The city with the world’s best airport, the most Instagrammable skyline, the most resilient in the face of global shocks.

Now, according to the latest global GDP rankings by The Economist, Singapore sits shoulder-to-shoulder with the world’s “richest” nations — top eight, depending on which calculation you favour, ahead of giants like the US, on par with Switzerland, Belgium, Norway, the Netherlands.

By all accounts, Singapore has arrived.

But statistics, like city skylines, are engineered to conceal as much as they reveal. “Richest” by what standard? GDP per person, at market exchange rates? Purchasing power, once you’ve stripped out the cost of living? Or, more subversively, GDP adjusted for the hours actually worked — an accounting for how much sweat, anxiety, and sacrifice is baked into every dollar?

Singapore excels at all three, but with each lens, the picture sharpens, then blurs. For every headline about prosperity, there is an undercurrent of apprehension, hinted at but rarely confronted directly.

This is not the complaint of a city that has fallen behind, but the growing unease of a society that has come perilously close to conflating contentment with mere survival.

What does it mean to be “rich” when satisfaction is paired, almost by reflex, with anxiety? What does it cost to remain at the summit — and who gets to pay that price?

A nation of achievers — but at what cost?

Let’s start with the numbers. According to The Economist, Singapore ranks in the global top eight for GDP per capita, even when you factor in price differences and the total hours worked by each citizen. Norway, Qatar, Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland, the US, the Netherlands — these are our economic peers, the blue-chip cohort of the 21st century.

But then you turn to the Knight Frank-Ipsos Quality of Life Report 2025 — a thick, data-heavy document designed to answer, for once, not how much we produce, but how we actually live. The results are telling.

Photo: Knight Frank-Ipsos

Seventy-five percent of Singaporeans say they’re satisfied with their housing. Fifty-six percent are satisfied with their jobs. Forty-nine percent are satisfied with their leisure options. On paper, this is what success looks like — an efficient, globally lauded, well-oiled machine.

Yet lurking beneath these percentages is a sharp, almost statistical irony: satisfaction and worry are now cohabitants.

Photo: Knight Frank-Ipsos

Of those who report being satisfied with their housing, a full 65% also say they are worried — or at least “somewhat worried” — that they won’t be able to afford a home in the next three to five years. Only 13% are truly untroubled. The rest are whistling in the dark, hoping the cost curve bends before it breaks them.

In the realm of work, the gap between perception and experience widens.

Photo: Knight Frank-Ipsos

Singaporean workers log more than 40 hours a week — often far more, according to the report. This is well above the averages in Germany, France, or the Netherlands.

Four out of ten Singaporeans experience work stress every week; one in five says it’s a daily visitor. And yet, the language of “satisfaction” persists.

Forty-five percent say they’re satisfied with their jobs, but just 11% reach for “extremely satisfied.” The rest are somewhere between stoicism and resignation, holding up the myth of balance in a country where, for many, the balance sheet is still written in hours and missed family dinners.

Leisure is no great escape, either. Asked about what they actually do for fun, Singaporeans rank dining out, shopping, and “leisure travel” highest — activities that are, for the most part, convenient, predictable, and safely commercial.

Only 8% put “Instagrammable activities” at the top.

Adventure and nightlife now trail far behind the search for value, convenience, and — most tellingly — scenic beauty and tranquility. When 69% of respondents name “ease of accessibility and convenience” as their number one recreational need, you begin to sense a culture of constant optimisation, not exuberance.

Engineered satisfaction, manufactured anxiety

This is where the two stories — of statistical success and lived apprehension — collide.

It’s fashionable to say that Singaporeans are pragmatic, that we have learned to adapt, to make do, to cope. But “coping” is not a synonym for thriving. And “satisfied,” as the Knight Frank-Ipsos numbers show, is a term increasingly elastic — capable of stretching over anxiety, resignation, and the quiet fear of being left behind.

Singapore’s rise is often told as a parable of discipline, foresight, and engineering — both social and physical. We have remade swamps into world-class real estate; we have codified every facet of urban life, from hawker centres to hospitals to housing blocks.

But with that mastery has come an unexpected cost: a creeping normalisation of low-grade dread. The very systems designed to keep us safe — affordable housing, good jobs, convenient amenities — are now the sources of our deepest uncertainty.

The report’s authors do not shy from this. They note that rising costs permeate all aspects of life.

Photo: Knight Frank-Ipsos

Fifty-two percent of respondents say this is their chief worry. Of those, housing is the epicentre. Thirty-five percent say they’re actively worried about being priced out in the near future; another 30% are “somewhat worried.”

In other words, two out of three Singaporeans face the future with a degree of trepidation that is entirely at odds with their city’s global reputation for stability.

Photo: Knight Frank-Ipsos

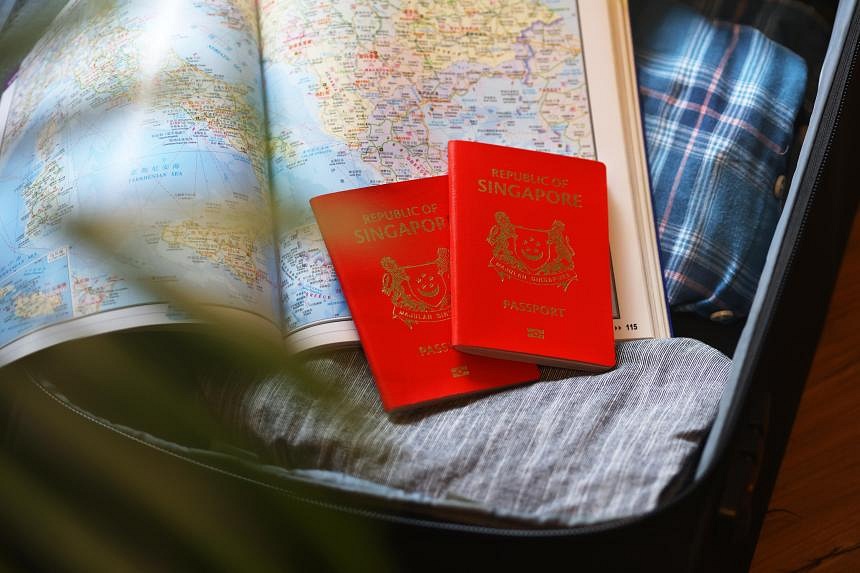

Is it any wonder? New private home sales have pulled away from household incomes, with the price-to-income ratio for new homes spiking from 11.8 in 2019 to a staggering 18.9 in 2024.

Even HDB flats, long the backbone of Singapore’s social contract, have seen their price-to-income ratios creep back toward the highs of 2013, when affordability was a national debate.

The trade-offs are palpable. Thirty percent are willing to pay more for a better location and connectivity. Twenty percent will accept a longer commute for a larger, quieter home. Eighteen percent would take an older, more spacious flat over a new, compact one.

These are not the decisions of a population secure in its prosperity — they are the accommodations of a society bracing for volatility.

The mirage of the modern city

And then there is work. The myth of Singaporean industriousness is alive and well. The reality, as the report notes, is more ambiguous.

Half the respondents work more than 40 hours a week, some well over 60. In other rich countries, this would be considered excessive, even abusive. Here, it is simply the price of admission.

The pandemic briefly rewrote the rules, introducing hybrid work and a flicker of hope for a gentler rhythm. But even now, only 28% of Singaporeans spend the bulk of their hours in the office; the rest float between home and workplace, negotiating new boundaries that are as likely to be violated as respected.

Related: SMEs dominate at NVPC’s Company of Good Ceremony in 2025

Related: SMEs dominate at NVPC’s Company of Good Ceremony in 2025

Forty-four percent prefer a structured hybrid model — two or three days in, two or three days out — a pattern now so entrenched that it may be Singapore’s new social contract.

But flexibility has its own discontents. Half the workforce reports weekly stress; 17% are stressed daily. The search for “work-life balance” is now the number one aspiration, cited by 79% — yet, in practice, it is an elusive promise. The pursuit of better ergonomic chairs, smarter offices, and wellness perks is, for many, a compensatory ritual. It is easier to install a nap pod than to grant a real lunch break; easier to tout mental health programs than to slow the pace.

The most telling statistic is this: only 11% of Singaporeans describe themselves as “extremely satisfied” with their jobs. The rest manage, adapt, persist — lucky to have a job, told to be grateful, always watching the cost of everything and the value of nothing.

A city that rarely lets go

If Singapore’s work ethic is relentless, its approach to leisure is similarly circumscribed.

The city is packed with “recreational amenities” — malls, parks, food courts, gyms, event spaces. But the appetite for exuberance is remarkably muted.

Dining out, travel, and shopping top the list of leisure activities, a catalogue of enjoyment that is predictably safe and reliably convenient. Parks and nature make a strong showing — 52% include them in their top five activities, a testament to the growing hunger for respite in a city whose green plan is more celebrated than its wildness.

“Ease of accessibility and convenience” is king. “Scenic beauty and relaxing environment” follows. What’s missing is a taste for surprise, for chaos, for serendipity. Even as the city state aspires to be a “playground for the world,” its residents seem content to let others play more noisily.

This is not an accident, but the result of decades of social engineering. The city’s relentless drive for efficiency and order has left little space for the unruly, the unpredictable, the inconvenient.

The city delivers everything you need, but not always what you desire.

The case for messiness

All of this raises a fundamental question, one that neither GDP statistics nor quality-of-life surveys can answer: At what point does the pursuit of prosperity begin to erode the foundations of contentment? When does the relentless chase for global “best-of” status stop producing more happiness and start generating more anxiety?

Singapore, at its heart, is a city that has always traded on its future. From independence, the promise was forward: tomorrow will be better, safer, richer, more secure. For decades, this was enough.

Today, as the city nears the outer limits of what can be engineered, a new mood is emerging — one that asks, “What now?”

Can a city be too efficient for its own good? Can a society so focused on stability begin to suffocate under the weight of its own anxieties?

Is it possible that, in becoming the “richest” city, Singapore has stumbled into a new kind of poverty — a poverty of imagination, of boldness, of risk?

The report offers few solutions, but it does issue a warning. Satisfaction, in the Singaporean context, is often indistinguishable from resignation. The willingness to adapt — to make do, to manage, to keep calm and carry on — is both a strength and a curse.

Toward a new ambition

If there is hope, it lies in the willingness to acknowledge this tension. Singapore’s achievement is not in doubt; what remains is the task of reckoning with its consequences.

The next phase will require a different kind of ambition — one less interested in global rankings and more focused on the lived, daily experiences of its citizens.

This means grappling seriously with the anxieties around housing affordability, with the chronic stress of overwork, with the limits of engineered leisure. It means asking what kind of city Singapore wants to be when the next crisis hits — one that can absorb shocks not just with money, but with meaning.

It may require a loosening of the grip, a toleration for more mess, more debate, more irreverence. It will almost certainly require policy that is more supple, more empathetic, more open to experiment.

The richest city in the world is not the one that produces the most, or spends the most, or saves the most.

It is the one where people wake up — safe, unafraid, ambitious for more than survival — and recognise, in the faces of their neighbours and in the streets of their city, a life worth living.

Singapore is rich. The next challenge is to become whole.

Related: SMEs dominate at NVPC’s Company of Good Ceremony in 2025

Related: SMEs dominate at NVPC’s Company of Good Ceremony in 2025