- Joined

- Feb 26, 2019

- Messages

- 12,449

- Points

- 113

biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg

A Chinatown shop front, c. 1870. Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Leiden, The Netherlands.

A Chinatown shop front, c. 1870. Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Niu che shui (牛车水) – literally “bullock water cart” in Chinese – is the historical Chinese enclave of Singapore, more popularly known as Chinatown. Demarcated by the Raffles Town Plan of 1822 and named after the bullock carts that used to supply fresh water to its residents, Chinatown is a much-visited place today, attracting tourists and locals who enjoy its distinctively Chinese ambience.

But Chinatown was a very different place in an earlier time. Behind the gentrified facades of restored shophouses, clan associations and temples lies a notorious and seedy past, buried in the annals of history. Apart from being overcrowded and filthy, Chinatown was probably the most unsafe part of the island, home to brazen secret societies and illegal activities, from gambling and opium-smoking to violent triad clashes and flagrant prostitution.

Although the British leased or granted land parcels to these early immigrants for living and commercial purposes, their general welfare was left in the hands of community leaders. This system of indirect rule led to the formation of mutual aid societies within the Chinese community. Referred to as hui, kongsi or huiguan (meaning clan), these societies, whose origins could be traced to the mid- and late-Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) in China, were usually organised along the lines of kinship and dialect. The societies relied on the notion of “brotherhood” or fictive kinship to unify their members. In return, the societies provided assistance in the form of financial support and resource sharing.

The Ghee Hin, regarded as Singapore’s first secret society, began innocently enough as a mutual aid organisation for the Chinese in Chinatown. With its headquarters on Rochor Road, the society was established in the 1820s to provide accommodation, job opportunities and security for new Chinese immigrants. In its earlier guise, Ghee Hin even helped the police maintain law and order and turned in members who broke the law.

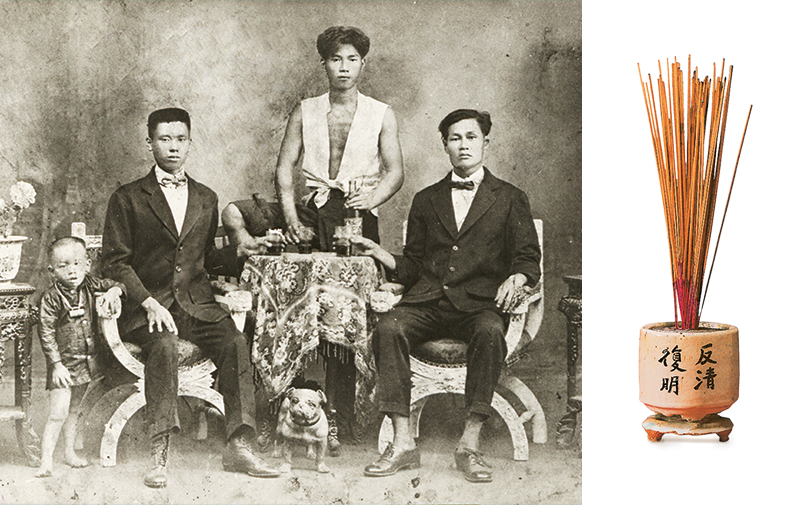

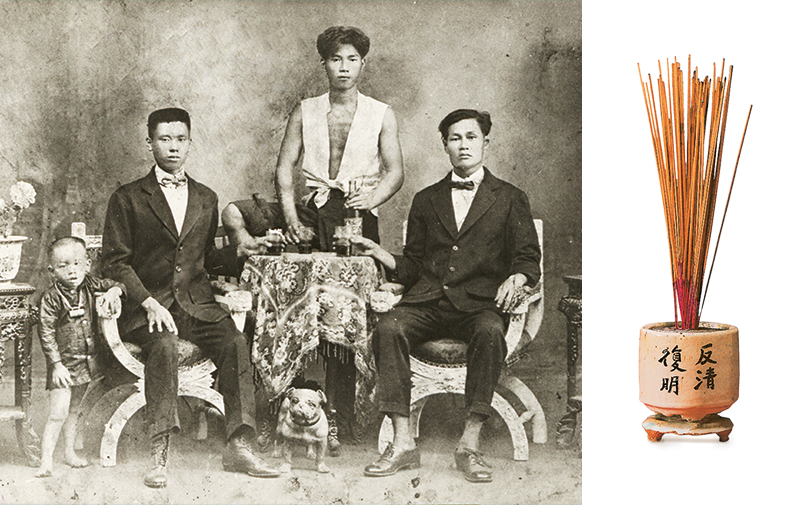

(Left) Chinese secret society members in early 20th-century Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Left) Chinese secret society members in early 20th-century Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Right) A censer of joss sticks used in the initiation altars of secret societies. Image reproduced from Frost, M.R., & Balasingamchow, Y. (2009). Singapore: A Biography. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS]).

As Ghee Hin grew in size and stature from the 1830s, it started to control the pepper and gambier plantations and rice trade, as well as the lucrative opium farms and vice industries. When rival groups by former Ghee Hin members as well as Chinese immigrants from dialect groups like the Teochews and Hakka emerged in the 1840s to challenge the dominance of Ghee Hin, bloody clashes broke out on the streets of Chinatown.

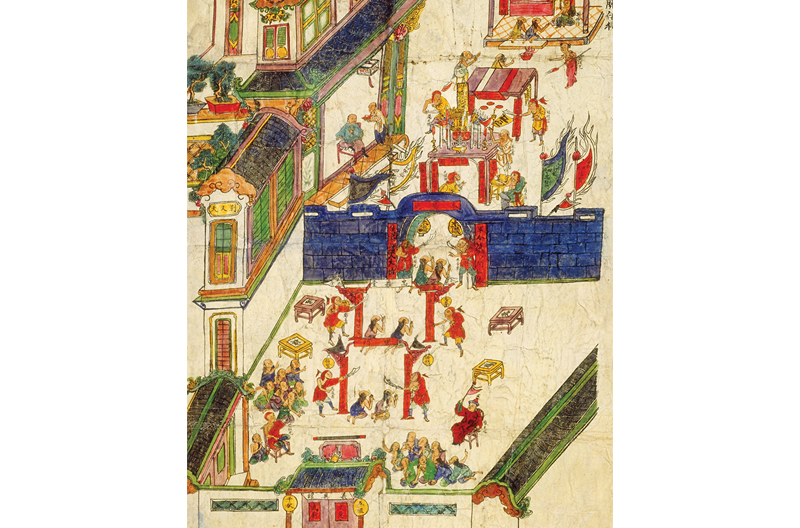

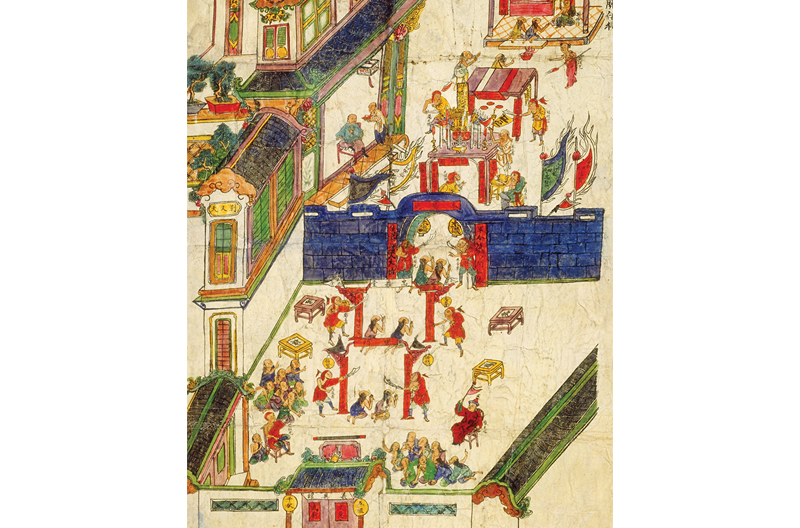

A watercolour painting of the Ghee Hin Kongsi lodge, showing details of an initiation ceremony. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A watercolour painting of the Ghee Hin Kongsi lodge, showing details of an initiation ceremony. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

One of the earliest occurred in March 1846 during the funeral procession of Ho Ah Yam, the leader of Ghee Hin. Referred to as “Huey Funeral Disturbances” in the English press at the time, the clash was between Ghee Hin and its rival Ghee Hok, a splinter group formed by former Ghee Hin members. The conflict started when some 6,000 Ghee Hin members diverted from their planned route from Rochor to the burial ground by taking a longer circuitous route through Kampong Glam, with the intention of passing Telok Ayer where Ghee Hok maintained a stronghold. Viewing it as an act of provocation, 2,000 to 3,000 armed Ghee Hok members confronted the rival party. Fortunately, the police, with the help of the army, managed to diffuse the situation.

In February 1851, Ghee Hin launched an attack against Christian Chinese-owned gambier and pepper plantations. Known as the Anti-Catholic Riots, the assault was directed at former Ghee Hin members who had eroded the society’s control over the gambier and pepper plantations when they left to join the Catholic faith. Initially, the attacks were confined to the plantations around the Kranji and Bukit Timah areas, but they soon spread to other plantations throughout the island. In response, Chinese Christians armed themselves and retaliated, while others fled to the city centre to seek refuge. The rampage lasted for about a week before it was quelled by the British. By then, nearly 500 Chinese had been murdered and at least 27 plantations looted or burnt.

Another serious altercation between Ghee Hin and Ghee Hok happened in May 1854, lasting 10 days. Known as the Teochew-Hokkien Riots or Singapore Riots of 1854, the clashes left some 500 people dead and the destruction of about 300 homes in Chinatown and other parts of the island.

The ostensible cause of the riots was a trivial quarrel between a Hokkien and a Teochew over the price of a few catties of rice on 5 May.1 The argument drew the attention of bystanders who began taking sides based on their affiliations to either the Hokkien-centric Ghee Hin or Teochew-based Ghee Hok.2 In a matter of hours, a street fight involving some 3,000 Chinese armed with spears and sticks broke out on North Bridge Road and spread to the adjourning streets. Amid the chaos, many shops in the area were also smashed and looted. Although the police and military were able to restore order, there were fresh violence and reprisal attacks in the ensuing days. The most intense fighting took place in the rural areas of Tanglin, Paya Lebar and Bukit Timah where pockets of Teochew and Hokkien communities resided.

In 1876, it was the British who found themselves at the receiving end of the wrath of the Chinese triads following their decision to regulate the remittance business between Singapore and China by setting up a government firm called Chinese Sub-Post Office. The new entity collected, at a fixed price, all China-bound letters and remittances, which were then sent via a postal system maintained by the colonial government. Unhappy that they had lost the monopoly of the remittance business, some Teochew merchants began spreading falsehoods about the Chinese Sub-Post Office, and instigated Ghee Hok and Ghee Hin to retaliate against the British.

The merchants spread rumours that it was mandatory to use the new post office for all letters and remittances, and alleged that it was an attempt by the colonial government to reap profit at the expense of the Chinese. In an act of open aggression, they offered a monetary reward to anyone willing “to cut off the head” of the post office operators. Matters escalated on the morning of 15 December 1876 when rioters stormed the sub-post office on the first day it opened. At the same time, riots also broke out at Kampong Glam and a police station on New Market Street. The riots were swiftly quelled due to the deft response of the police. However, three people died and many others, including British police superintendent, R. W. Maxwell, were wounded.

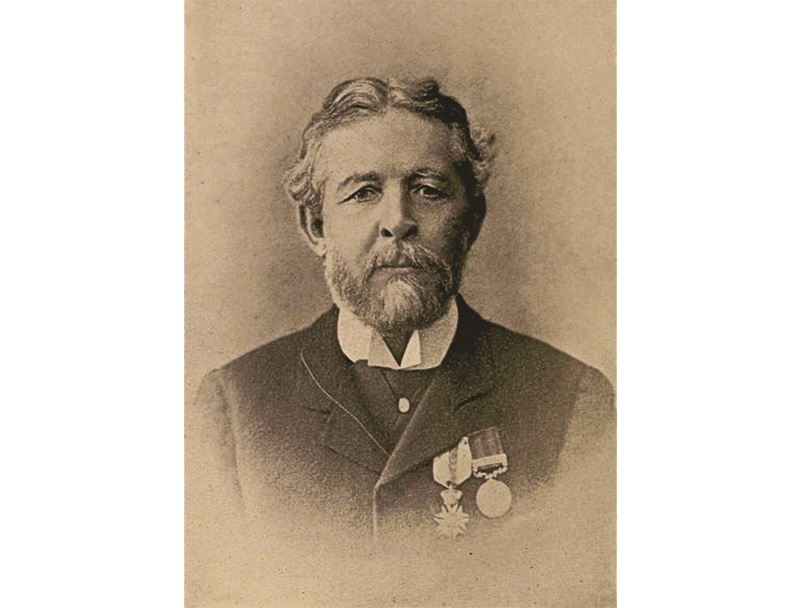

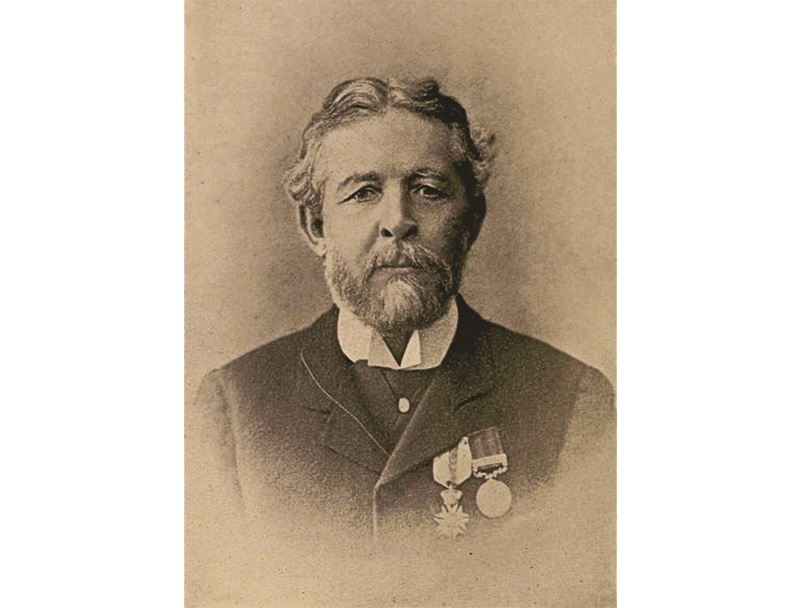

In 1877, the British set up the Chinese Protectorate to manage the secret societies and curb their activities through surveillance and control. One such measure was the registration of secret societies so that the government could obtain pertinent information such as the name, location, headman and members of each society. However, this move ran into trouble when the first Protector, the Chinese linguist William A. Pickering, was attacked by triads in 1887.

William A. Pickering (1840–1907) was the first Protector of Chinese appointed by the British government to oversee the Chinese Protectorate in Singapore. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

William A. Pickering (1840–1907) was the first Protector of Chinese appointed by the British government to oversee the Chinese Protectorate in Singapore. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

In 1889, the British responded by introducing the Societies Ordinance to abolish triad activity in the Straits Settlements. As a result, secret societies began to lose their influence and quickly diminished in numbers. Some went underground while others registered themselves as recreational or social groups, but still continued with their illegal activities. It was only in the late 1950s that their activities were curtailed through tougher criminal laws and police crackdowns – such as Operation Dagger (1956), Operation Pereksa (1957) and Operation Sapu (1958) – against the secret societies.

Coolies could be distinguished by two types – “free coolies” and “credit coolies”. The former paid for their passage and decided where they went or what they would do upon reaching their destination. Credit coolies, on the other hand, were practically penniless. On arrival at their destination, credit coolies were required to sign binding contracts with their employers.

Chinese coolies sharing a meal and enjoying the camaraderie, circa 1900. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chinese coolies sharing a meal and enjoying the camaraderie, circa 1900. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Coolies had been flooding Singapore’s shores since the arrival of the British. In 1830, Singapore received nearly 7,000 Chinese labourers during the junk season,3 which was almost the size of the entire Chinese population of the island at the time. In the subsequent decades, new coolies numbering between 5,000 and 7,000, would arrive in Singapore yearly, grossly overcrowding the Chinatown area. As the coolies were usually unskilled, they were employed as manual labour in almost every sector from construction to plantation work. They were also hired to take on back-breaking jobs such as rickshaw pullers and stevedores. During periods when labour supply was tight, coolies were highly sought after by plantation owners, merchants and port operators. However, during lull times, coolies were summarily regarded as “destitute and worthless”.

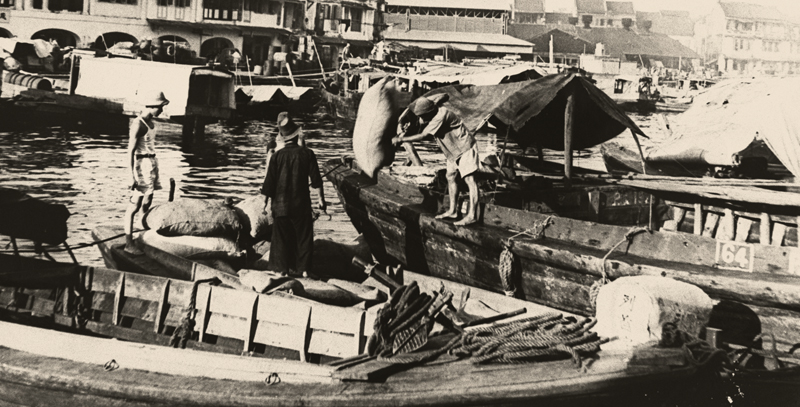

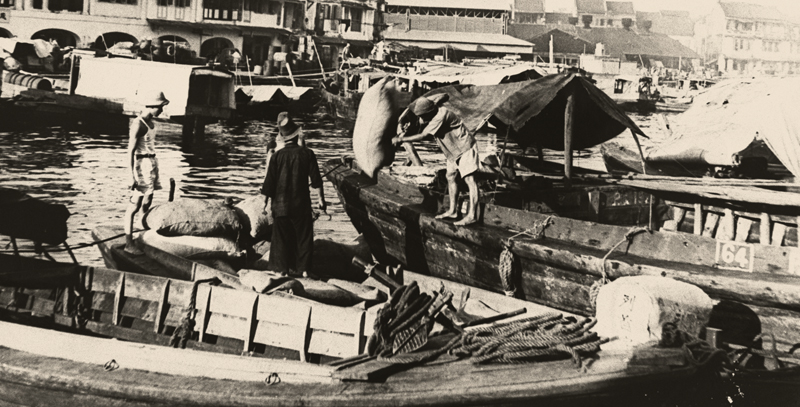

Chinese coolies transporting goods along the Singapore River in 1948. Coolies were typically used for manual labour and back-breaking tasks. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chinese coolies transporting goods along the Singapore River in 1948. Coolies were typically used for manual labour and back-breaking tasks. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The condescending attitude towards the coolies would persist until Singapore’s entrepot economy took off from the 1870s onwards when plantations and mining industries in Malaya began to flourish. With the tap of Indian convict labour turned off in 1873, Chinese coolies provided a source of cheap labour for these British-run enterprises in the Straits Settlements and Malaya. This led to a surge in demand and resulted in a huge inflow of coolies into Singapore from the southern provinces of Fujian, Guangdong and Hainan in China, reaching around 50,000 annually in the 1870s before hitting 200,000 by the turn of the 19th century.

The rising demand, however, did not improve the plight of the coolies. Whether they were travelling as free coolies or under the credit ticket system, the coolies had to endure a harrowing voyage by sea to Singapore. They were piled into small vessels and herded like cattle across the often stormy South China Sea in cramped and unsanitary conditions.

Their suffering continued upon arrival in Singapore. Some credit coolies were held in the hull of the ships until a contractor or broker for the mines or plantations agreed to take on their debt. Others were confined in dark and stuffy coolie-holding stations without proper sanitation and fresh water. Pagoda Street in Chinatown was home to many coolie-holding stations. In 1901, for example, it had 12 stations and each was licensed to accommodate up to 200 coolies. In reality, each held far more people. Kwong Hup Yuen was one of the largest coolie trade firms on Pagoda Street, so well known that residents in the area referred to the street by the firm’s Cantonese name – Kwong Hup Yuen Kai.

Free coolies fared better than credit coolies, provided they were not duped by secret societies and ended up in their debt. Regardless, both free and credit coolies led a difficult life of hard labour and grinding poverty. The average salary of a coolie was so meagre it was hardly enough to cover his basic expenses. For example, in 1924, a rickshaw puller made about 20 to 24 Straits dollars a month. As the monthly cost of living at the time was roughly 12 to 14 Straits dollars, this meant the coolie only had eight to 10 Straits dollars each month to remit back to China, leaving him with almost nothing.

Furthermore, the condition of their living quarters (or coolie kengs in Hokkien) in Chinatown was appalling, even by hardened Chinese standards. Stephen Dobbs describes the dreadful living conditions in The Singapore River: A Social History, 1819–2002 (2003):

“The standard of living conditions prevalent in these older two and three storey houses were shocking to the extreme. Cubicles measuring only a few feet across were shared by several men, and sometimes even families, taking turn to rest and work. With little light and ventilation and even less provision for sanitary requirements, morbidity and mortality from communicable diseases… were common place.”

In the 1930s, coolie quarters were a common sight in Chinatown. The coolies lived in deplorable and unsanitary conditions with little light and poor ventilation. The cubicles were shared by several men and sometimes even families. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In the 1930s, coolie quarters were a common sight in Chinatown. The coolies lived in deplorable and unsanitary conditions with little light and poor ventilation. The cubicles were shared by several men and sometimes even families. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Coolie quarters were found in almost every part of Chinatown on Duxton Road, Kim Seng Road, Telok Ayer Street, Pagoda Street and Sago Lane. To improve the housing situation and alleviate the overcrowding problem in Chinatown, the colonial government set up the Singapore Improvement Trust in 1927, which built a new town with mass housing and better sanitation in nearby Tiong Bahru.

The Chinese Protectorate did their part to help the coolies by distributing handbills and advising them of the protection they were entitled to in Singapore. However, the impact of these measures was minimal and the Chinese coolies continued to suffer much hardship, including at the hands of the secret societies. It was only when the British introduced the Labour Contracts Ordinance in 1914 to abolish indentured labour that the coolie trade started declining in Singapore. But until then, in order to escape from the harsh reality of their lives, the coolies turned to the few sources of comfort and entertainment available at the time, namely, the opium den, gambling table and brothel.

In 1848, there were 45 licensed opium shops; by 1900, this had grown to 550. Many were conveniently located in the heart of Chinatown on Pagoda Street, Trengganu Street, Duxton Road and Amoy Street. Similarly, there was an increase in the number of gambling dens throughout the 19th century despite being outlawed in 1829. In 1832, there were at least 20 gambling dens operating illegally on Church Street near Telok Ayer. By the end of the 19th century, this had grown to about 100 found in both the outskirts of the town centre and Chinatown. The number of brothels also increased, from 212 in 1877 to 353 in 1905, and many were located on Upper Hokkien Street, Chin Hin Street, Smith Street, Sago Street and Banda Street.

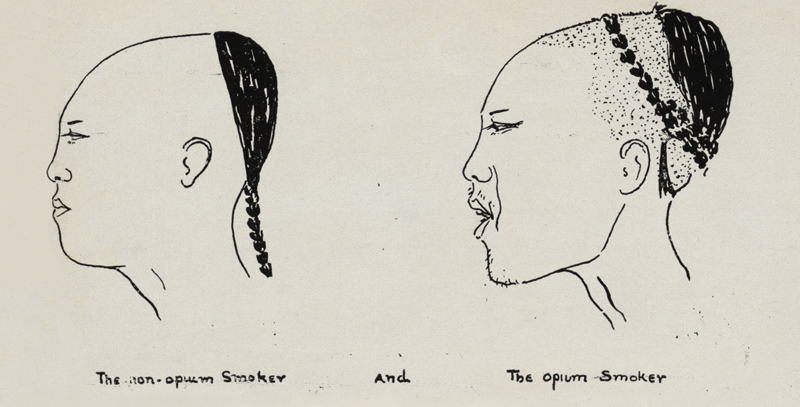

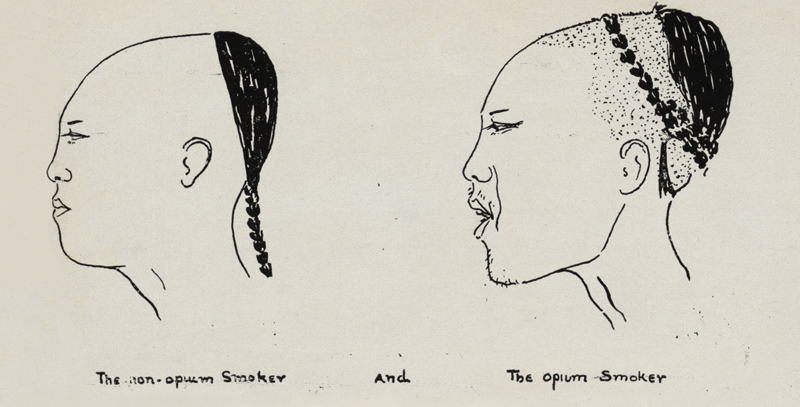

Illustrations comparing the side profile of a non-opium smoker (left) and an opium smoker. Image reproduced from Stirling, W.G. (1913). Opium Smoking Among the Chinese. Times of Malaya Press. (Microfilm no.: NL7462).

Illustrations comparing the side profile of a non-opium smoker (left) and an opium smoker. Image reproduced from Stirling, W.G. (1913). Opium Smoking Among the Chinese. Times of Malaya Press. (Microfilm no.: NL7462).

What perpetuated the growth of these social ills in 19th-century Singapore? The rise of opium shops was a result of the opium farming system created by the colonial government. Under this system, the government monopolised the supply of raw opium and leased the rights of preparing and distributing the opiate to wealthy Chinese merchants or syndicates. As both sides made handsome profits out of the system, opium dens were allowed to thrive with almost no restrictions.

The proliferation of gambling establishments, on the other hand, was due to the deficiency of the law. After outlawing gambling in 1829, the colonial government did not follow up with strong measures to suppress it. Rather, it continued to rely on existing ordinances that were gravely ineffective in resolving the gambling problem. For instance, the Police Act of 1856 treated gambling offenders leniently with only a fine.

Although the police tried to eradicate illegal gambling dens with frequent raids, they were often hampered by den operators who either hired thugs as guards or by shifting location regularly. The dens also resorted to other methods of gambling such as lotteries that did not require any premises.

The growth of brothels was linked to the severely disproportionate gender ratio in Singapore at the time. In 1860, for example, Singapore’s population was about 81,000, with a ratio of one female to 14 males. In the eyes of the colonial administrators, this social structure was problematic and in no sense natural. As a result, the government sanctioned the establishment of brothels in Singapore to cater to the needs of the male population. By 1882, there were at least 2,000 prostitutes in Singapore, constituting about one-third of the female population.

The growth of the three vices had an adverse effect on the Chinese community and took decades to rectify. In 1906, an anti-opium movement was started and this led to the Opium Commission in 1907, which spearheaded anti-opium measures such as the enactment of the Chandu Revenue Ordinance in 1909 and the creation of the Monopolies Department a year later to control the sale and distribution of opium. In 1933, treatment for opium addicts became available after Chen Su Lan, a medical doctor and president of the Singapore Anti-Opium Society, started a rehabilitation clinic. Despite these measures, including a complete ban of opium sales after World War II, opium-smoking was prevalent right up to the 1980s. It was only until the implementation of the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1989 that the use of opium was effectively curbed in Singapore.

Gambling, too, had a devastating impact on the newly arrived Chinese. Hardcore gamblers often failed to make regular remittances to their families in China. If the addict incurred huge gambling debts, there was a high chance that he would commit suicide or, worse, sell his wife and children to pay off his debts. Like opium, resolving the gambling problem was a long process that involved suppressing the secret societies, who were the main operators of gambling dens, ridding the police force of corruption, and introducing stronger anti-gambling measures; the latter included setting up the Gambling Suppression Department in 1889 and passing the Gaming Housing Ordinance in 1870 that banned the popular Wha Whey lottery.4

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the government regulated gambling by establishing Singapore Pools in 1968. The police also came down hard on gambling dens and stronger legislation like the Common Gaming Houses Act made gambling houses illegal.

One of the biggest social problems that arose from prostitution was the rampant spread of venereal diseases. As brothel owners did not subject their prostitutes to regular health checks, many who had contracted sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhoea or syphilis continued to ply their trade, resulting in an epidemic in the 1890s when thousands of people were infected yearly.

Prostitution ruined the lives of countless of women and young girls. Similar to the coolies, these women, who hailed mainly from the southern provinces of China, did not become prostitutes of their own volition. Many were either lured under false pretences or sold by their impoverished families. Prostitution was a lucrative business managed by wealthy merchants and the secret societies – with 350 Straits dollars to be made from the earnings of each prostitute. Abused by their pimps and forced to work in dark and filthy cubicles with a constant risk of contracting venereal diseases, many turned to opium-smoking or even committed suicide to escape from their sordid lives.

Fortunately, the Chinese Protectorate sought out victims of forced prostitution and rescued them from the brothels. The rescued females were sent to a safe refuge managed by the Office for the Preservation of Virtue (Po Leung Kuk in Cantonese) where they were taught English and Chinese as well as domestic skills. The refuge home started as a single room in Lock Hospital in Kandang Kerbau before it was expanded to accommodate up to 120 girls. In 1928, the home moved to larger premises at York Hill in the Chinatown area so that it could accommodate more women.

Looking at the gentrified Chinatown of today, it is difficult to imagine its tainted past. The next time you walk past an old shophouse in Chinatown, now resplendently conserved and housing a stylish cafe or bar, take a moment to appreciate its history and pay homage to our forefathers who toiled behind those facades to make Singapore what it is today.

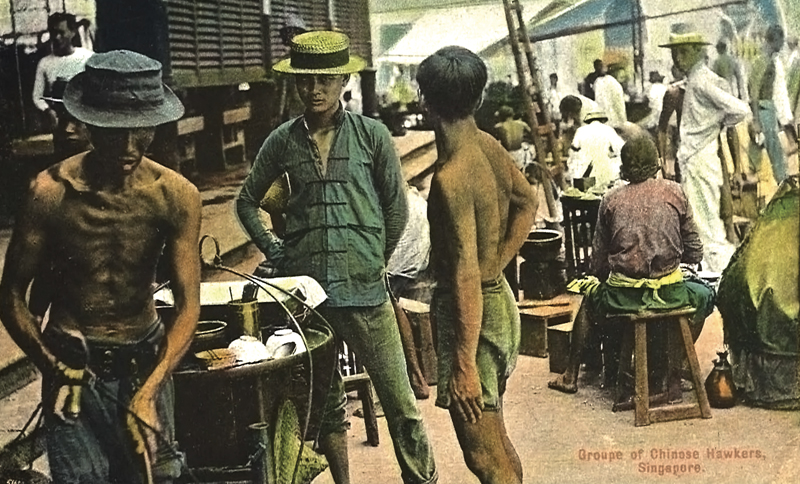

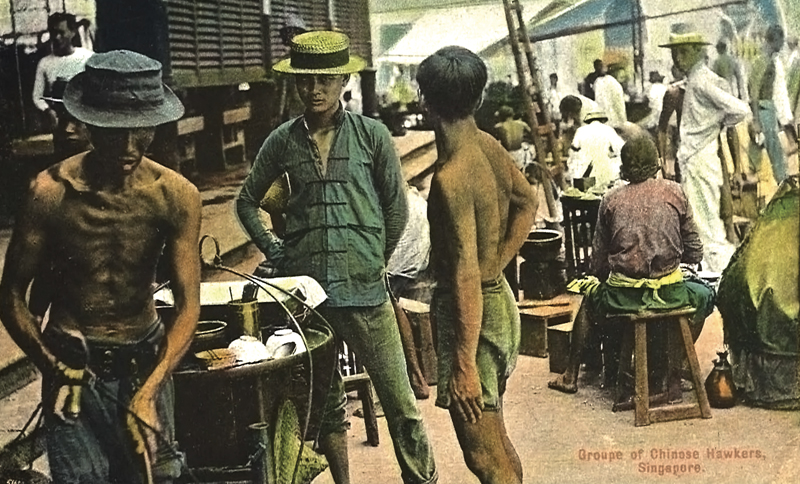

Chinese street hawkers plying their trade outside Telok Ayer Market, c. 1915. Courtesy of Farish Noor.

Chinese street hawkers plying their trade outside Telok Ayer Market, c. 1915. Courtesy of Farish Noor.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Back to Issue

Blythe, W. (1969). The impact of Chinese secret societies in Malaya: A historical study. London: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 366.09595 BLY)

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore: 1819–1867. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC)

Dobbs, S. (2003). The Singapore River: A social history, 1819–2002. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 DOB)

Hinkelman, E.G. (2005). Dictionary of international trade. Novato, Calif.: World Trade Press. (Call no.: RBUS q382.03 HIN)

Huey funeral disturbances. (1846, March 18). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lee, E. (1991). The British as rulers governing multi-racial Singapore, 1867–1914. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57022 LEE)

Lim, I. (1999). Secret societies in Singapore: Featuring the William Stirling Collection. Singapore: National Heritage Board, Singapore History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 366.095957 LIM)

Local. (1851, February 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869), p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Saw, S.H. (2012). The population of Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW)

Sharp, I. (1998). Just a little flutter: The Singapore pools story. Singapore: Singapore Pools. (Call no.: RSING 336.1095957 SHA)

Singapore. Archives and Oral History Dept. (1983). Chinatown: An album of a Singapore community. Singapore: Times Books International: Archives and Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 779.995957 CHI)

Special Criminal Session. (1854, June 13). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tanjong Pagar Citizens’ Consultative Committee. (1989). Tanjong Pagar: Singapore’s cradle of development. Singapore: Tanjong Pagar Citizens’ Consultative Committee. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TAN)

The riot reports. (1877, February 8). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Trocki, C.A. (1990). Opium and empire: Chinese society in Colonial Singapore, 1800–1910. New York: Cornell University Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 TRO)

Trocki, C.A. (1993). The rise and fall of the Ngee Heng Kongsi in Singapore. In D. Ownby & M. S. F. Heidhues. (Eds.). “Secret societies” reconsidered: Perspectives on the social history of modern South China and Southeast Asia. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. (Call no.: RSING 366 SEC)

Trocki, C.A. (2011). Singapore as a nineteenth century migration node. In D.R. Gabaccia & D. rHoerder. (Eds.). Connecting seas and connected ocean rims: Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific oceans and China seas migrations from the 1830s to the 1930s. Leiden; Boston: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 304.809034 CON)

Turnbull, C.M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR)

Wang, D.F., Ong, T.H., & Isralowitz, R.E. (1996). Substance use in Singapore: Illegal drugs, inhalants and alcohol. Singapore: Toppan Company. (Call no.: RSING 362.29095957 ONG)

Warren, J.F. (2003). Ah ku and karayuki-san: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870–1940. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.74095957 WAR)

Warren, J.F. (2003). Rickshaw coolie: A people’s history of Singapore, 1880–1940. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 388.341 WAR)

Yan, Q. (1986). A social history of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya, 1800–1911. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 301.45195105957 YEN)

Yeoh, B. S. A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: power relations and the urban built environment. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO)

Triads, Coolies and Pimps: Chinatown in Former Times

The Chinatown of yesteryear was a thriving hotbed of crime and secret societies. Lim Tin Seng unveils its less glamorous history.

Niu che shui (牛车水) – literally “bullock water cart” in Chinese – is the historical Chinese enclave of Singapore, more popularly known as Chinatown. Demarcated by the Raffles Town Plan of 1822 and named after the bullock carts that used to supply fresh water to its residents, Chinatown is a much-visited place today, attracting tourists and locals who enjoy its distinctively Chinese ambience.

But Chinatown was a very different place in an earlier time. Behind the gentrified facades of restored shophouses, clan associations and temples lies a notorious and seedy past, buried in the annals of history. Apart from being overcrowded and filthy, Chinatown was probably the most unsafe part of the island, home to brazen secret societies and illegal activities, from gambling and opium-smoking to violent triad clashes and flagrant prostitution.

The Rise of Secret Societies

The development of Chinatown as the enclave for newly arrived Chinese immigrants in Singapore took place in tandem with the progress of the island as a British port. Chinatown quickly established itself as the second largest ethnic district, housing one-third of the population. By 1836, it had become the largest district with more than 13,700 Chinese settlers. The Chinese immigrants who settled there did not reside as they pleased within the area but were housed by the British in different locations based on their origin and dialect group.Although the British leased or granted land parcels to these early immigrants for living and commercial purposes, their general welfare was left in the hands of community leaders. This system of indirect rule led to the formation of mutual aid societies within the Chinese community. Referred to as hui, kongsi or huiguan (meaning clan), these societies, whose origins could be traced to the mid- and late-Tang dynasty (AD 618–907) in China, were usually organised along the lines of kinship and dialect. The societies relied on the notion of “brotherhood” or fictive kinship to unify their members. In return, the societies provided assistance in the form of financial support and resource sharing.

The Ghee Hin, regarded as Singapore’s first secret society, began innocently enough as a mutual aid organisation for the Chinese in Chinatown. With its headquarters on Rochor Road, the society was established in the 1820s to provide accommodation, job opportunities and security for new Chinese immigrants. In its earlier guise, Ghee Hin even helped the police maintain law and order and turned in members who broke the law.

(Right) A censer of joss sticks used in the initiation altars of secret societies. Image reproduced from Frost, M.R., & Balasingamchow, Y. (2009). Singapore: A Biography. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS]).

As Ghee Hin grew in size and stature from the 1830s, it started to control the pepper and gambier plantations and rice trade, as well as the lucrative opium farms and vice industries. When rival groups by former Ghee Hin members as well as Chinese immigrants from dialect groups like the Teochews and Hakka emerged in the 1840s to challenge the dominance of Ghee Hin, bloody clashes broke out on the streets of Chinatown.

One of the earliest occurred in March 1846 during the funeral procession of Ho Ah Yam, the leader of Ghee Hin. Referred to as “Huey Funeral Disturbances” in the English press at the time, the clash was between Ghee Hin and its rival Ghee Hok, a splinter group formed by former Ghee Hin members. The conflict started when some 6,000 Ghee Hin members diverted from their planned route from Rochor to the burial ground by taking a longer circuitous route through Kampong Glam, with the intention of passing Telok Ayer where Ghee Hok maintained a stronghold. Viewing it as an act of provocation, 2,000 to 3,000 armed Ghee Hok members confronted the rival party. Fortunately, the police, with the help of the army, managed to diffuse the situation.

In February 1851, Ghee Hin launched an attack against Christian Chinese-owned gambier and pepper plantations. Known as the Anti-Catholic Riots, the assault was directed at former Ghee Hin members who had eroded the society’s control over the gambier and pepper plantations when they left to join the Catholic faith. Initially, the attacks were confined to the plantations around the Kranji and Bukit Timah areas, but they soon spread to other plantations throughout the island. In response, Chinese Christians armed themselves and retaliated, while others fled to the city centre to seek refuge. The rampage lasted for about a week before it was quelled by the British. By then, nearly 500 Chinese had been murdered and at least 27 plantations looted or burnt.

Another serious altercation between Ghee Hin and Ghee Hok happened in May 1854, lasting 10 days. Known as the Teochew-Hokkien Riots or Singapore Riots of 1854, the clashes left some 500 people dead and the destruction of about 300 homes in Chinatown and other parts of the island.

The ostensible cause of the riots was a trivial quarrel between a Hokkien and a Teochew over the price of a few catties of rice on 5 May.1 The argument drew the attention of bystanders who began taking sides based on their affiliations to either the Hokkien-centric Ghee Hin or Teochew-based Ghee Hok.2 In a matter of hours, a street fight involving some 3,000 Chinese armed with spears and sticks broke out on North Bridge Road and spread to the adjourning streets. Amid the chaos, many shops in the area were also smashed and looted. Although the police and military were able to restore order, there were fresh violence and reprisal attacks in the ensuing days. The most intense fighting took place in the rural areas of Tanglin, Paya Lebar and Bukit Timah where pockets of Teochew and Hokkien communities resided.

In 1876, it was the British who found themselves at the receiving end of the wrath of the Chinese triads following their decision to regulate the remittance business between Singapore and China by setting up a government firm called Chinese Sub-Post Office. The new entity collected, at a fixed price, all China-bound letters and remittances, which were then sent via a postal system maintained by the colonial government. Unhappy that they had lost the monopoly of the remittance business, some Teochew merchants began spreading falsehoods about the Chinese Sub-Post Office, and instigated Ghee Hok and Ghee Hin to retaliate against the British.

The merchants spread rumours that it was mandatory to use the new post office for all letters and remittances, and alleged that it was an attempt by the colonial government to reap profit at the expense of the Chinese. In an act of open aggression, they offered a monetary reward to anyone willing “to cut off the head” of the post office operators. Matters escalated on the morning of 15 December 1876 when rioters stormed the sub-post office on the first day it opened. At the same time, riots also broke out at Kampong Glam and a police station on New Market Street. The riots were swiftly quelled due to the deft response of the police. However, three people died and many others, including British police superintendent, R. W. Maxwell, were wounded.

In 1877, the British set up the Chinese Protectorate to manage the secret societies and curb their activities through surveillance and control. One such measure was the registration of secret societies so that the government could obtain pertinent information such as the name, location, headman and members of each society. However, this move ran into trouble when the first Protector, the Chinese linguist William A. Pickering, was attacked by triads in 1887.

In 1889, the British responded by introducing the Societies Ordinance to abolish triad activity in the Straits Settlements. As a result, secret societies began to lose their influence and quickly diminished in numbers. Some went underground while others registered themselves as recreational or social groups, but still continued with their illegal activities. It was only in the late 1950s that their activities were curtailed through tougher criminal laws and police crackdowns – such as Operation Dagger (1956), Operation Pereksa (1957) and Operation Sapu (1958) – against the secret societies.

The Plight of the Coolies

Chinatown was also synonymous with the coolie trade. Coolies were male labourer immigrants who were forced to leave China due to famine and unrest in order to seek a better life in foreign lands. This sojourn was usually temporary as many harboured the intention of returning to China with money in their pockets.Coolies could be distinguished by two types – “free coolies” and “credit coolies”. The former paid for their passage and decided where they went or what they would do upon reaching their destination. Credit coolies, on the other hand, were practically penniless. On arrival at their destination, credit coolies were required to sign binding contracts with their employers.

Coolies had been flooding Singapore’s shores since the arrival of the British. In 1830, Singapore received nearly 7,000 Chinese labourers during the junk season,3 which was almost the size of the entire Chinese population of the island at the time. In the subsequent decades, new coolies numbering between 5,000 and 7,000, would arrive in Singapore yearly, grossly overcrowding the Chinatown area. As the coolies were usually unskilled, they were employed as manual labour in almost every sector from construction to plantation work. They were also hired to take on back-breaking jobs such as rickshaw pullers and stevedores. During periods when labour supply was tight, coolies were highly sought after by plantation owners, merchants and port operators. However, during lull times, coolies were summarily regarded as “destitute and worthless”.

The condescending attitude towards the coolies would persist until Singapore’s entrepot economy took off from the 1870s onwards when plantations and mining industries in Malaya began to flourish. With the tap of Indian convict labour turned off in 1873, Chinese coolies provided a source of cheap labour for these British-run enterprises in the Straits Settlements and Malaya. This led to a surge in demand and resulted in a huge inflow of coolies into Singapore from the southern provinces of Fujian, Guangdong and Hainan in China, reaching around 50,000 annually in the 1870s before hitting 200,000 by the turn of the 19th century.

The rising demand, however, did not improve the plight of the coolies. Whether they were travelling as free coolies or under the credit ticket system, the coolies had to endure a harrowing voyage by sea to Singapore. They were piled into small vessels and herded like cattle across the often stormy South China Sea in cramped and unsanitary conditions.

Their suffering continued upon arrival in Singapore. Some credit coolies were held in the hull of the ships until a contractor or broker for the mines or plantations agreed to take on their debt. Others were confined in dark and stuffy coolie-holding stations without proper sanitation and fresh water. Pagoda Street in Chinatown was home to many coolie-holding stations. In 1901, for example, it had 12 stations and each was licensed to accommodate up to 200 coolies. In reality, each held far more people. Kwong Hup Yuen was one of the largest coolie trade firms on Pagoda Street, so well known that residents in the area referred to the street by the firm’s Cantonese name – Kwong Hup Yuen Kai.

Free coolies fared better than credit coolies, provided they were not duped by secret societies and ended up in their debt. Regardless, both free and credit coolies led a difficult life of hard labour and grinding poverty. The average salary of a coolie was so meagre it was hardly enough to cover his basic expenses. For example, in 1924, a rickshaw puller made about 20 to 24 Straits dollars a month. As the monthly cost of living at the time was roughly 12 to 14 Straits dollars, this meant the coolie only had eight to 10 Straits dollars each month to remit back to China, leaving him with almost nothing.

Furthermore, the condition of their living quarters (or coolie kengs in Hokkien) in Chinatown was appalling, even by hardened Chinese standards. Stephen Dobbs describes the dreadful living conditions in The Singapore River: A Social History, 1819–2002 (2003):

“The standard of living conditions prevalent in these older two and three storey houses were shocking to the extreme. Cubicles measuring only a few feet across were shared by several men, and sometimes even families, taking turn to rest and work. With little light and ventilation and even less provision for sanitary requirements, morbidity and mortality from communicable diseases… were common place.”

Coolie quarters were found in almost every part of Chinatown on Duxton Road, Kim Seng Road, Telok Ayer Street, Pagoda Street and Sago Lane. To improve the housing situation and alleviate the overcrowding problem in Chinatown, the colonial government set up the Singapore Improvement Trust in 1927, which built a new town with mass housing and better sanitation in nearby Tiong Bahru.

The Chinese Protectorate did their part to help the coolies by distributing handbills and advising them of the protection they were entitled to in Singapore. However, the impact of these measures was minimal and the Chinese coolies continued to suffer much hardship, including at the hands of the secret societies. It was only when the British introduced the Labour Contracts Ordinance in 1914 to abolish indentured labour that the coolie trade started declining in Singapore. But until then, in order to escape from the harsh reality of their lives, the coolies turned to the few sources of comfort and entertainment available at the time, namely, the opium den, gambling table and brothel.

Opium, Gambling and Prostitution

Opium-smoking, gambling and prostitution were the three biggest social ills that plagued the Chinese community in Chinatown. The partakers of these vices came from all social classes of the community regardless of background or profession. The vices became rooted in the Chinese community due to several factors. Options for entertainment were practically non-existent; there were no cinemas or music venues, and operas organised by the voluntary organisations or clans were only staged during festivals. Given the social structure of the early Chinese community – predominantly male sojourners who faced hardship on a daily basis – it is easy to see why they were tempted by the plentiful opium shops, gambling dens and brothels found in Chinatown.In 1848, there were 45 licensed opium shops; by 1900, this had grown to 550. Many were conveniently located in the heart of Chinatown on Pagoda Street, Trengganu Street, Duxton Road and Amoy Street. Similarly, there was an increase in the number of gambling dens throughout the 19th century despite being outlawed in 1829. In 1832, there were at least 20 gambling dens operating illegally on Church Street near Telok Ayer. By the end of the 19th century, this had grown to about 100 found in both the outskirts of the town centre and Chinatown. The number of brothels also increased, from 212 in 1877 to 353 in 1905, and many were located on Upper Hokkien Street, Chin Hin Street, Smith Street, Sago Street and Banda Street.

What perpetuated the growth of these social ills in 19th-century Singapore? The rise of opium shops was a result of the opium farming system created by the colonial government. Under this system, the government monopolised the supply of raw opium and leased the rights of preparing and distributing the opiate to wealthy Chinese merchants or syndicates. As both sides made handsome profits out of the system, opium dens were allowed to thrive with almost no restrictions.

The proliferation of gambling establishments, on the other hand, was due to the deficiency of the law. After outlawing gambling in 1829, the colonial government did not follow up with strong measures to suppress it. Rather, it continued to rely on existing ordinances that were gravely ineffective in resolving the gambling problem. For instance, the Police Act of 1856 treated gambling offenders leniently with only a fine.

Although the police tried to eradicate illegal gambling dens with frequent raids, they were often hampered by den operators who either hired thugs as guards or by shifting location regularly. The dens also resorted to other methods of gambling such as lotteries that did not require any premises.

The growth of brothels was linked to the severely disproportionate gender ratio in Singapore at the time. In 1860, for example, Singapore’s population was about 81,000, with a ratio of one female to 14 males. In the eyes of the colonial administrators, this social structure was problematic and in no sense natural. As a result, the government sanctioned the establishment of brothels in Singapore to cater to the needs of the male population. By 1882, there were at least 2,000 prostitutes in Singapore, constituting about one-third of the female population.

The growth of the three vices had an adverse effect on the Chinese community and took decades to rectify. In 1906, an anti-opium movement was started and this led to the Opium Commission in 1907, which spearheaded anti-opium measures such as the enactment of the Chandu Revenue Ordinance in 1909 and the creation of the Monopolies Department a year later to control the sale and distribution of opium. In 1933, treatment for opium addicts became available after Chen Su Lan, a medical doctor and president of the Singapore Anti-Opium Society, started a rehabilitation clinic. Despite these measures, including a complete ban of opium sales after World War II, opium-smoking was prevalent right up to the 1980s. It was only until the implementation of the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1989 that the use of opium was effectively curbed in Singapore.

Gambling, too, had a devastating impact on the newly arrived Chinese. Hardcore gamblers often failed to make regular remittances to their families in China. If the addict incurred huge gambling debts, there was a high chance that he would commit suicide or, worse, sell his wife and children to pay off his debts. Like opium, resolving the gambling problem was a long process that involved suppressing the secret societies, who were the main operators of gambling dens, ridding the police force of corruption, and introducing stronger anti-gambling measures; the latter included setting up the Gambling Suppression Department in 1889 and passing the Gaming Housing Ordinance in 1870 that banned the popular Wha Whey lottery.4

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the government regulated gambling by establishing Singapore Pools in 1968. The police also came down hard on gambling dens and stronger legislation like the Common Gaming Houses Act made gambling houses illegal.

One of the biggest social problems that arose from prostitution was the rampant spread of venereal diseases. As brothel owners did not subject their prostitutes to regular health checks, many who had contracted sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhoea or syphilis continued to ply their trade, resulting in an epidemic in the 1890s when thousands of people were infected yearly.

Prostitution ruined the lives of countless of women and young girls. Similar to the coolies, these women, who hailed mainly from the southern provinces of China, did not become prostitutes of their own volition. Many were either lured under false pretences or sold by their impoverished families. Prostitution was a lucrative business managed by wealthy merchants and the secret societies – with 350 Straits dollars to be made from the earnings of each prostitute. Abused by their pimps and forced to work in dark and filthy cubicles with a constant risk of contracting venereal diseases, many turned to opium-smoking or even committed suicide to escape from their sordid lives.

Fortunately, the Chinese Protectorate sought out victims of forced prostitution and rescued them from the brothels. The rescued females were sent to a safe refuge managed by the Office for the Preservation of Virtue (Po Leung Kuk in Cantonese) where they were taught English and Chinese as well as domestic skills. The refuge home started as a single room in Lock Hospital in Kandang Kerbau before it was expanded to accommodate up to 120 girls. In 1928, the home moved to larger premises at York Hill in the Chinatown area so that it could accommodate more women.

Looking at the gentrified Chinatown of today, it is difficult to imagine its tainted past. The next time you walk past an old shophouse in Chinatown, now resplendently conserved and housing a stylish cafe or bar, take a moment to appreciate its history and pay homage to our forefathers who toiled behind those facades to make Singapore what it is today.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Back to Issue

REFERENCES

Anti-opium society’s fine work. (1937, March 18). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.Blythe, W. (1969). The impact of Chinese secret societies in Malaya: A historical study. London: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 366.09595 BLY)

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore: 1819–1867. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC)

Dobbs, S. (2003). The Singapore River: A social history, 1819–2002. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 DOB)

Hinkelman, E.G. (2005). Dictionary of international trade. Novato, Calif.: World Trade Press. (Call no.: RBUS q382.03 HIN)

Huey funeral disturbances. (1846, March 18). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Lee, E. (1991). The British as rulers governing multi-racial Singapore, 1867–1914. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57022 LEE)

Lim, I. (1999). Secret societies in Singapore: Featuring the William Stirling Collection. Singapore: National Heritage Board, Singapore History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 366.095957 LIM)

Local. (1851, February 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869), p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV)

Saw, S.H. (2012). The population of Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW)

Sharp, I. (1998). Just a little flutter: The Singapore pools story. Singapore: Singapore Pools. (Call no.: RSING 336.1095957 SHA)

Singapore. Archives and Oral History Dept. (1983). Chinatown: An album of a Singapore community. Singapore: Times Books International: Archives and Oral History Department. (Call no.: RSING 779.995957 CHI)

Special Criminal Session. (1854, June 13). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tanjong Pagar Citizens’ Consultative Committee. (1989). Tanjong Pagar: Singapore’s cradle of development. Singapore: Tanjong Pagar Citizens’ Consultative Committee. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TAN)

The riot reports. (1877, February 8). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Trocki, C.A. (1990). Opium and empire: Chinese society in Colonial Singapore, 1800–1910. New York: Cornell University Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 TRO)

Trocki, C.A. (1993). The rise and fall of the Ngee Heng Kongsi in Singapore. In D. Ownby & M. S. F. Heidhues. (Eds.). “Secret societies” reconsidered: Perspectives on the social history of modern South China and Southeast Asia. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. (Call no.: RSING 366 SEC)

Trocki, C.A. (2011). Singapore as a nineteenth century migration node. In D.R. Gabaccia & D. rHoerder. (Eds.). Connecting seas and connected ocean rims: Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific oceans and China seas migrations from the 1830s to the 1930s. Leiden; Boston: Brill. (Call no.: RSING 304.809034 CON)

Turnbull, C.M. (2009). A history of modern Singapore, 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR)

Wang, D.F., Ong, T.H., & Isralowitz, R.E. (1996). Substance use in Singapore: Illegal drugs, inhalants and alcohol. Singapore: Toppan Company. (Call no.: RSING 362.29095957 ONG)

Warren, J.F. (2003). Ah ku and karayuki-san: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870–1940. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.74095957 WAR)

Warren, J.F. (2003). Rickshaw coolie: A people’s history of Singapore, 1880–1940. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 388.341 WAR)

Yan, Q. (1986). A social history of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya, 1800–1911. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 301.45195105957 YEN)

Yeoh, B. S. A. (2003). Contesting space in colonial Singapore: power relations and the urban built environment. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO)