The seed has been sown. Look at Amsterdam now. It wasn't like that 50 years ago.

How Amsterdam became the bicycle capital of the world

In the 1960s, Dutch cities were increasingly in thrall to motorists, with the car seen as the transport of the future. It took the intolerable toll of child traffic deaths – and fierce activism – to turn Amsterdam into the cycling nirvana of today

Cities is supported by

About this content

Renate van der Zee

About this content

Renate van der Zee

Tue 5 May 2015 03.04 EDTLast modified on Fri 11 May 2018 08.15 EDT

Shares

17,382

Comments

787

Stop de Kindermoord

Stop de Kindermoord campaigners visit Amsterdam’s House of Representatives in 1972, a year after more than 400 children were killed in traffic accidents. Photograph: Fotocollectie Anefo/Society for the Nationaal Archief

Anyone who has ever tried to make their way through the centre of Amsterdam in a car knows it: the city is owned by cyclists. They hurry in swarms through the streets, unbothered by traffic rules, taking precedence whenever they want, rendering motorists powerless by their sheer numbers.

Cyclists rule in Amsterdam and great pains have been taken to accommodate them: the city is equipped with an elaborate network of cycle-paths and lanes, so safe and comfortable that even toddlers and elderly people use bikes as the easiest mode of transport. It’s not only Amsterdam which boasts a network of cycle-paths, of course; you’ll find them in all Dutch cities.

The Dutch take this for granted; they even tend to believe these cycle-paths have existed since the beginning of time. But that is certainly not the case. There was a time, in the 1950s and 60s, when cyclists were under severe threat of being expelled from Dutch cities by the growing number of cars. Only thanks to fierce activism and a number of decisive events would Amsterdam succeed in becoming what it is, unquestionably, now: the bicycle capital of the world.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

FacebookTwitterPinterest

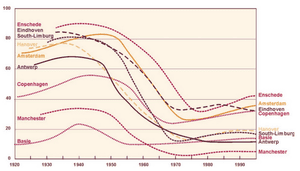

The share of trips made by bicycle in Amsterdam plunged from 80% to 20% between the 1950s and 70s. Source: Bruheze and Veraart

At the start of the 20th century, bikes far outnumbered cars in Dutch cities and the bicycle was considered a respectable mode of transport for men and women. But when the Dutch economy began to boom in the post-war era, more and more people were able to afford cars, and urban policymakers came to view the car as the travel mode of the future. Entire Amsterdam neighbourhoods were destroyed to make way for motorised traffic. The use of bikes decreased by 6% every year, and the general idea was that bicycles would eventually disappear altogether.

The streets no longer belonged to the people who lived there, but to huge traffic flows

Maartje van Putten, former MEP

All that growing traffic took its toll. The number of traffic casualties rose to a peak of 3,300 deaths in 1971. More than 400 children were killed in traffic accidents that year.

This staggering loss led to protests by different action groups, the most memorable of which was

Stop de Kindermoord (“stop the child murder”). Its first president was the Dutch former MEP, Maartje van Putten.

“I was a young mother living in Amsterdam and I witnessed several traffic accidents in my neighbourhood where children got hurt,” van Putten, 63, recalls. “I saw how parts of the city were torn down to make way for roads. I was very worried by the changes that took place in society – it affected our lives. The streets no longer belonged to the people who lived there, but to huge traffic flows. That made me very angry.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest

FacebookTwitterPinterest

In the 1960s planners viewed the car as the travel mode of the future, and swaths of the city were destroyed to make way for motorised traffic. Photograph: Fotocollectie Anefo/Society for the Nationaal Archief

The 1970s were a great time for being angry in Holland: activism and civil disobedience were rampant.

Stop de Kindermoord grew rapidly and its members held bicycle demonstrations, occupied accident blackspots, and organised special days during which streets were closed to allow children to play safely: “We put tables outside and held a huge dinner party in our street. And the funny thing was, the police were very helpful.”

Van Putten remembers the 70s as a time when Dutch authorities were remarkably accessible: “We simply went to tea with MPs – and they really listened to what we had to say. We cycled with a group of activists and an organ grinder to the house of the prime minister, Joop den Uyl, to sing songs and ask for safer streets for children. We didn’t get beyond the hallway, but he did come out to hear our plea.”

We had a great fighting spirit and we knew how to voice our ideas. And in the end, we would get our bicycle lane

Tom Godefrooij

Stop de Kindermoord became subsidised by the Dutch government, established its headquarters in a former shop, and went on to develop ideas for safer urban planning – which eventually resulted in the

woonerf: a new kind of people-friendly street with speed bumps and bends to force cars to drive very slowly. Nowadays the

woonerf has gone out of fashion, but it can still be found in many Dutch cities.

Two years after

Stop de Kindermoord was established, another group of activists founded the First Only Real Dutch Cyclists’ Union to demand more space for bicycles in the public realm – organising bike rides along dangerous stretches of road, and compiling inventories of the problems encountered by cyclists.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

FacebookTwitterPinterest

An estimated 38% of all trips in Amsterdam are made by bike – compared with 2% in London. Photograph: Tony Burns/Getty Images/Lonely Planet Image

“Somehow we managed to strike a chord,” says Tom Godefrooij, 64, who got involved with the Cyclists’ Union as a young man. He remembers noisy mass demonstrations with tricycles and megaphones, and nightly ventures to paint illegal bicycle lanes in streets the union considered dangerous.

Sign up for the Cityscape: the best of Guardian Cities every week

Read more

“First we would be arrested by the police, of course, but then the whole thing would be in the newspapers and municipal politicians would eventually listen. We had a great fighting spirit and we knew how to voice our ideas. And in the end, we would get our bicycle lane. Even in the 70s, you know, there were politicians who understood that the general focus on cars would eventually cause problems.”

The activists of

Stop de Kindermoord and the Cyclists’ Union were resourceful and undaunted, but there were other forces helping to create a fertile soil for their ideas. The

Netherlands – possessing few hills and a mild climate – had a great tradition of cycling to begin with and the bike was never completely marginalised as it was in some other countries. The intolerable number of traffic deaths really was a serious concern for politicians, and there was a nascent awareness of the pollution caused by vehicle emissions.

The 1973 oil crisis – when Saudi Arabia and other Arab oil exporters imposed an embargo on the US, Britain, Canada, Japan and the Netherlands for supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur war – quadrupled the price of oil. During a television speech, prime minister Den Uyl urged Dutch citizens to adopt a new lifestyle and get serious about saving energy. The government proclaimed a series of car-free Sundays: intensely quiet weekend days when children played on deserted motorways and people were suddenly reminded of what life was like before the hegemony of the car.

FacebookTwitterPinterest

FacebookTwitterPinterest

Amsterdam is now home to an estimated 881,000 bicycles. Photograph: Timothy Clary/AFP/Getty

On one of these car-free Sundays, Maartje van Putten, together with a group of other parents and children, rode her bike through a tunnel to the northern part of Amsterdam, in which no provisions for cyclists had been made. “We didn’t realise that what we did was dangerous, because there were still some cars on the road. Our trip ended at the police station, but we made our point.”

Gradually, Dutch politicians became aware of the many advantages of cycling, and their transport policies shifted – maybe the car wasn’t the mode of transport of the future after all. In the 1980s, Dutch towns and cities began introducing measures to make their streets more cycle-friendly. Initially, their aims were far from ambitious; the idea was simply to keep cyclists on their bikes.

The Hague and Tilburg were the first to experiment with special cycle routes through the city. “The bicycle paths were bright red and very visible; this was something completely new,” says Godefrooij. “Cyclists would change their routes to use the paths. It certainly helped to keep people on their bikes, but in the end it turned out that one single bicycle route did not lead to an overall increase in cycling.”

Subsequently, the city of Delft constructed a whole network of cycle paths and it turned out that this did encourage more people to get on their bikes. One by one, other cities followed suit.

Nowadays the Netherlands boasts 22,000 miles of cycle paths. More than a quarter of all trips are made by bicycle, compared with 2% in the UK – and this rises to 38% in Amsterdam and 59% in the university city of Groningen. All major Dutch cities have designated “bicycle civil servants”, tasked to maintain and improve the network. And the popularity of the bike is still growing, thanks partly to the development of electric bicycles.

The Cyclists’ Union has long ceased to be a group of random activists; it is now a respectable organisation with 34,000 paying members whose expertise is in worldwide demand.

End of the car age: how cities are outgrowing the automobile

Read more

“We have achieved a lot, but we’re facing many new challenges,” says their spokesman, Wim Bot. “Many old cycle paths need to be reconstructed because they do not measure up to our modern standards – some are used by so many people that they are no longer wide enough. We have the problem of parking all those bikes, and we are thinking of new ways to create even more space for cyclists and pedestrians. What our cities really need is a totally new kind of infrastructure. They’re simply not fit for so much car traffic.”

“The battle goes on,” says Godefrooij. “The propensity of urban planners to give priority to cars is still persistent. It’s easy to understand: an extra tunnel for cyclists means you have to spend extra money on the project. We’ve come a long way, but we can never lower our guard.”

At this critical time…

… we can’t turn away from climate change. For The Guardian, reporting on the environment is a priority. We give climate, nature and pollution stories the prominence they deserve, stories which often go unreported by others in the mainstream media. At this critical time for our species and our planet, we are determined to inform readers about threats, consequences and solutions based on scientific facts, not political prejudice or business interests. But we need your support to grow our coverage, to travel to the remote frontlines of change and to cover vital conferences that affect us all.

More people are reading and supporting our independent, investigative reporting than ever before. And unlike many news organisations, we have chosen an approach that allows us to keep our journalism accessible to all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to give a voice to those less heard, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

Every contribution we receive from readers like you, big or small, goes directly into funding our journalism. This support enables us to keep working as we do – but we must maintain and build on it for every year to come.

Support The Guardian from as lit