Doctor diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer learns lessons on death, dying and compassion

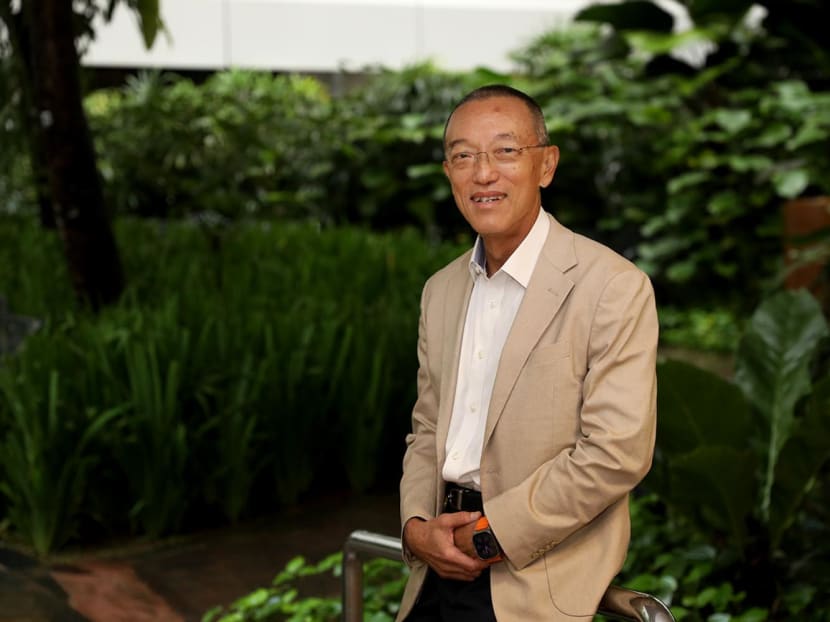

Professor Christopher Cheng (pictured), a senior consultant urologist, used to be the chief executive officer of Sengkang General Hospital.

Professor Christopher Cheng (pictured), a senior consultant urologist, used to be the chief executive officer of Sengkang General Hospital.

Follow us on Instagram and Tiktok, and join our Telegram channel for the latest updates.

A senior consultant urologist specialising in prostate cancer was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer himself

Professor Christopher Cheng, 66, is among 20 doctors featured in a video series called Doctors’ Die-logues

The doctors share their diverse experiences and perspectives on death and dying in the series

The videos produced by Lien Foundation aim to help healthcare professionals get a better understanding of the topic of death and the need for compassionate care

The professor told of the “humbling” lessons he learnt while battling cancer and his own emotional ups and downs

SINGAPORE — Having dedicated more than three decades of his career to the field of urology focused on prostate cancer, Professor Christopher Cheng was aware of the sobering possibility that he may eventually succumb to the very same disease he knows well as a specialist.

In 2017, the urologist and trailblazer in the use of robots for surgery found himself on the other side of the treatment room after becoming a patient himself.

Advertisement

He was diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer and underwent treatment. However, the disease recurred.

In an interview with TODAY, Prof Cheng, who completed radiation therapy in December 2021 for the recurrence, offered his perspective on death and dying as a doctor who battled a life-threatening disease.

The 66-year-old is a senior consultant urologist with Singapore General Hospital and Sengkang General Hospital.

‘But he’s a guy’: Singaporean pancreatic cancer patient in his 30s tests positive for mutated gene linked to breast cancer

“I have a 50 per cent chance of being on pal (palliative) care eventually, with the recurrence,” he said candidly.

Palliative care is a patient-centred approach that enhances the quality of life for patients and their families who are coping with life-threatening illnesses such as cancer.

Advertisement

EQUAL CHANCE OF MIRACLE OR DEATH

Prof Cheng is among 20 eminent doctors featured in a series of video interviews called Doctors’ Die-logues.

Produced by the Lien Foundation, it is part of a new focus to help healthcare professionals gain a better understanding of the topic of death and dying, and the need for compassionate care.

Lien Foundation, a Singapore-based philanthropic organisation, has been championing training, research and advocacy for end-of-life care for more than a decade.

In the video, Prof Cheng said: “Scientifically, based on databases and whatever I tell my patients... (I would also say to myself), 'I think you have a 50-50 chance — 50 per cent chance that you’ll have a miracle and 50 per cent chance you’ll die of the disease.”

Advertisement

The conference was organised by the Singapore Hospice Council, with Lien Foundation as one of the supporting partners.

As a nation, Singapore aims to boost palliative care services, including home palliative care, and reduce the proportion of people dying in hospitals.

In a past survey by Lien Foundation, 77 per cent of Singaporeans expressed hopes of dying at home but only about a quarter (26 per cent) managed to do so.

The lack of awareness of such services, even among healthcare professionals here, had been highlighted as one of the key barriers.

In a 2020 survey done by the Singapore Hospice Council, less than half (around 46 per cent) of the respondents — who included doctors, nurses and allied healthcare professionals — were familiar with hospice and palliative care service providers and referral processes in Singapore.

Most Singaporeans want a 'good death', but majority don't get their wish: Study

“Also, I’ve had (urinary) symptoms for many years since I was a teenager. So my self-diagnosis was that it is very unlikely that it was cancer,” he said.

In 2017, a time in which Prof Cheng jokingly referred to as “all hell break loose days” when he and his team were up to their neck preparing for the opening of Sengkang General Hospital, a prostate examination revealed a suspicious nodule and likely prostate cancer.

He was the chief executive officer of the new hospital then.

The finding was unexpected because he had attributed his urinary symptoms to an enlarged prostate, a benign condition, and had scheduled surgery during the year-end festive break in 2017 to relieve the symptoms.

He recalled receiving results of his PSA blood test while in the midst of a meeting. It was at a “shockingly high” level of 17.8 nanograms per decilitre (ng/dL), which he knew spelled bad news for anyone with prostate cancer.

The PSA is a substance produced by the prostate, which is the small gland that sits below the bladder in males.

Commentary: It takes a village to care for the terminally ill — and here’s how all can help

“It’s either relief or disappointment, multiple (times of) fear, anxiety, anticipation.

His experience has changed the way he informs patients of their progress. Previously, for patients with a good PSA test result, he would print out the result and congratulate them.

“Now I do an extra step,” he said. “If I see an undetectable PSA after surgery, I give the patient a hug and I may have tears in my eyes. Because I think they are free.”

Professor Christopher Cheng (pictured) hopes that young doctors would be more aware of the importance of connecting with patients at a deeper “heart” level as a medical practitioner, and put it into practice.

While being on the receiving end of cancer treatment has given him better insights into what his patients go through and greater empathy, Prof Cheng pointed out that no one can claim to truly walk in another person’s shoes.

Even when experiences may seem similar, every individual would have a different perception of their lived experience.

“After the surgery and treatment, I also thought that, okay, I've been through all these complications, all these experiences, I can show my patients the (surgical) scars and tell them ‘I know how you feel’.

‘COMPASSION FATIGUE OVERRATED’

During the interview, Prof Cheng brought up the topic of compassion, which is also a recurring theme in his book.

Experiencing what it is like to be a patient has made him more mindful of the importance of connecting with patients at a deeper “heart” level as a medical practitioner.

This is something he hopes that young doctors would be more aware of and put into practice as well, even when facing seemingly challenging patients.

His personal take on “compassion fatigue” — which some may consider controversial — is that it is “overrated”.

“I think that in giving compassion and care, you receive double the amount,” he said in the video interview.

More younger adults planning end-of-life care during Covid-19 crisis, one healthcare provider sees 8-fold jump in a year

The term “compassion fatigue” describes the physical, emotional and psychological impact resulting from repeated exposure to traumatised individuals or adverse traumatic events.

It is commonly reported among people who work in a helping profession, such as in healthcare, and can desensitise healthcare professionals to the needs of their patients, causing them to lack empathy.

Prof Cheng’s take is that when it is a good day’s worth of work, “you go home dead tired but you’ve had a fulfilling day”.

“If our heart is true, I don’t think that compassion, by itself, can lead to fatigue.”

Recounting a talk he gave earlier this year on compassion for a group of first-year medical students, Prof Cheng told TODAY that he extended an offer to the students to visit his clinic.

“I said, when you guys are tired and burned out, come to my clinic and connect with the patients. What burnout is there when you can connect with a human being?

ON HAVING A 'GOOD DEATH’

As a doctor who has seen patients at death’s door, Prof Cheng came to the realisation that death is an experience that everyone faces alone.

“However rich, however powerful (they) are, they’ve all had to face death eventually. They all have to let go,” he said.

The difference, however, lies in how one faces death.

Once, he asked a patient whose disease had worsened how he was coping, to which he replied, “I have no complaint. I can eat, I can urinate, I can pass motion. I’m okay”.

“I thought, wow, this was really contentment with very little. And he had no angst.”

Sleep habits of Singapore doctors: What we can learn from their attempts to get a better night’s rest

“I opted out of it and decided to have very focal, localised (treatment). After a long, long discussion, I didn’t want an all-out treatment that would most likely give me many side effects,” he added.

“People ask me, 'So, how are you?', they are concerned. (I tell them) I'm as good as could be, nothing to panic.

“I’ve everything I need to be happy, and more. I don't think that being at the receiving end of the kitchen sink is going to make me any happier.”

Prof Cheng is considering writing “season two” of his experience but expressed some hesitation over it.

“Part of the reason is because one man's experience is a drop in the ocean. When you write something, you need to basically present a scientific account because people will hang on to those little things.”

For now, he is doubling up his efforts to live life to the fullest, and to be fully present in all that he does.

“No more postponing meeting the people I really like to catch up with; no more procrastinating on things I would like to complete. Every task is taken as though it is the last chance,” he said.

“For the first time, I have a cycling coach and I am winning races for the first time in my life. My paintings are now exhibited, good enough to be sold for charity. Most of all, I make peace with things I accept as being beyond me.

“Every moment is precious. Every encounter is ‘here and now’, like this (interview), at 100 per cent attention,” he added.

“And I’m not in a hurry to go anywhere.”

The Lien Foundation's Doctors' Die-logues video series can be found online.