Soaring COE prices: What’s driving the insanity, and when will it end?

Christopher Tan

Senior Transport Correspondent

Besides supply and demand, there are several factors driving COE prices up. PHOTO: ST FILE

Apr 23, 2023

SINGAPORE - Nearly 30 years ago, the Government refuted a June 1994 Business Times article which stated that certificate of entitlement (COE) prices would soon skyrocket on the back of an imminent shrinkage in supply because of fewer vehicles being deregistered – the main determinant of COE supply.

In a letter to the editor, the then Ministry of Communications (the precursor of the Transport Ministry) argued that fewer deregistrations also meant that fewer people were bidding for COEs to replace their deregistered vehicles.

“In such a situation – where a reduction in supply of COEs is accompanied by a corresponding reduction in demand for COEs – it does not follow that COE prices will ‘shoot through the roof again’,” it wrote.

As it turned out, COE prices shot through the roof, with the premium for bigger cars hitting $110,500 by end-1994 – a record that would stand for more than 20 years.

The surge, however, had little to with supply or demand. It had to do with speculation, where motor traders secured as many COEs as they could in the hope of pairing them with buyers.

And when they failed, they would quickly register the cheapest vehicle – in this case, the smallest motorcycles back then – with the unused COEs, and deregister the bikes to recoup the COE amount. Their losses were thus limited to cost of the mini-bikes.

The Government, which was refunding tens of millions of dollars to these speculators, acted swiftly to plug this loophole, by making car COEs non-transferable. The following month, all car COE prices plunged, with the premium for bigger cars nearly halved to $65,000.

It is not wrong to postulate that replacement demand is a determinant of COE prices. But there are several other factors which are equally important and are usually amplified when the COE supply is small.

For starters, people do not buy cars once every 10 years (the lifespan of a COE). Many buy them every three to five years, often when the warranty of their existing car runs out. In addition, Singapore has seen an influx of foreigners since the Covid-19 pandemic kicked in. Many of them seek to buy cars, which adds fuel to the frenzy.

On their part, car sellers fan demand further by dangling promotions, or by telling consumers they should buy soon because COE prices will go higher. The latter becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when consumers are swayed by this fear tactic.

And speculation – which drove prices to insane levels three decades ago – may well have returned in a new form.

The premium for bigger and more powerful cars hit a new record of $120,889 at the latest tender on April 19. Its proxy, COE in the Open category (which remains transferable), also set a new high of $124,501. The COE for smaller, less powerful cars is likewise at a record $103,721 – well past a level which triggered the Monetary Authority of Singapore to reintroduce car loan curbs 10 years ago (which cooled prices immediately).

While this latest round of hikes could be attributed to expectations of another supply shrinkage in the May-July quota period, motor traders point to private-hire vehicle operators as one underlying driver of runaway prices.

From the time ride-hailing firms entered Singapore 10 years ago, the private-hire fleet has been growing aggressively. From just 16,396 in 2013, it reached a record 77,141 in 2019 – swelling nearly five times in just six years, grossly outpacing the overall car population growth of 1.5 per cent in the same period.

Amid the Covid-19 pandemic, the private-hire fleet shrank to 67,990 in 2021.

Growth resumed thereafter, with the fleet hitting 72,632 at end-December 2022, and 73,982 at end-February 2023. This represents an 8.8 per cent growth from 2021, while the rest of the car population crept up by merely 0.1 per cent in the same time frame.

With tourism returning to pre-pandemic levels, and with no regulatory cap on private-hire fleet size in sight, operators will likely continue to grow their fleet.

There are points of similarity between private-hire firms and the speculators who drove COE prices to six-digit levels three decades ago.

One, they are able to pass higher cost to vehicle hirers (drivers). Two, they are able to dispose of unhired cars by converting them into normal cars and selling them as used vehicles. Three, the more vehicles they acquire, the fewer can be sold to individual consumers, which in turn sets the stage for higher demand for rental cars.

In short, they are able to mitigate their risks. In fact, the only real risk they face is when COE prices start to slide when the uptrend in supply comes (starting as early as next year). When this happens, they will be stuck with an expensive fleet of cars which they cannot rent out or resell.

Motorists currently driving private-hire cars because they are priced out of the car market by stratospheric COE rates will stop driving them when COEs return to saner levels. In that sense, it is in the interest of private-hire firms to keep bidding aggressively to keep premiums high for as long as possible.

Unlike 1994, the Government on its part, faces no revenue risk this time round. It has nonetheless been trying to cool the market.

In Budget 2023,

far more punitive taxes were introduced for costlier cars – mostly those with bigger or more powerful engines or motors. This has worked to some degree. Since February, the price increase in COE for bigger, more powerful cars has been smaller (+14.6 per cent) than the increase in COE for smaller, less powerful cars (+20.6 per cent).

This has also partly to do with consumers switching to the cheaper category of cars, and sellers importing more models which qualify for the cheaper COE category.

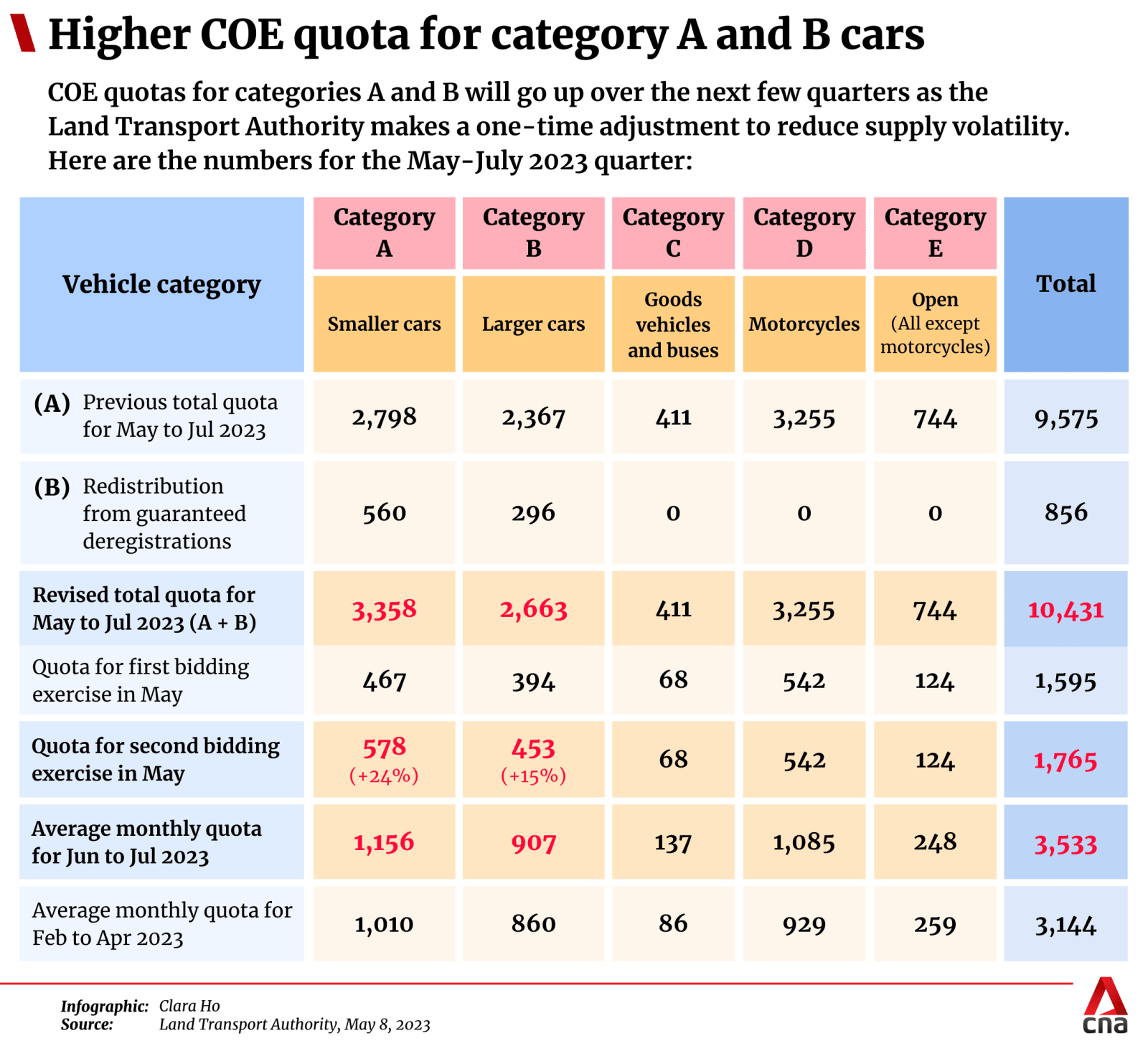

The Land Transport Authority has also tweaked the supply formula twice since July 2022, first, by basing each quarter’s quota on deregistrations of the preceding two quarters, and then, in January, expanding it to deregistrations of the preceding four quarters. This is meant to reduce supply volatility.

This cooled the market briefly, but clearly more needs to be done.

Make a decisive policy change to treat private-hire cars like taxis since they serve the same role as taxis. Cap their fleet size. Have an age limit on private-hire cars. Ban the conversion of private-hire cars to normal cars – or at least stipulate a minimum no-conversion period. Demand that ride-hailing firms adopt a transparent fare structure – the way taxi and public transport fares are transparent.

Will this affect fares and service availability? Unlikely.

The recent hikes in point-to-point transport fares and longer waiting time had less to do with a dip in driver supply than with drivers tailoring their driving pattern to maximise fares, and platform owners looking to increase profit margins. After all, the point-to-point vehicle fleet is now at more than 60,000 – more than double the taxi fleet in 2012 (before private-hire firms arrived).

Separately, the drive towards cleaner cars may be indirectly driving COE prices up. Sellers are using part of the tax incentives to price their hybrid or electric cars in such a way that they secure a more decent profit margin. This way, they are able to outbid others – such as those selling cars without incentives – to secure more COEs.

There must be a way where Singapore can encourage the adoption of cleaner vehicles without inadvertently driving up cost of all vehicles. Some cities use methods such as preferential access to restricted areas and income tax offsets to drive the green initiative.

COE premium for smaller cars surges to $103,721; Open category hits all-time high of $124,501

Lastly, easy credit underpins all the factors cited above. While car loans are still restricted to 70 per cent of selling price and tenure limited to seven years, loopholes exist. One, cars bought on leasing plans do not have these restrictions. Two, sellers have been inflating list prices to overcome the curbs. Three, cars registered under companies – such as private-hire firms – do not have to observe the restrictions.

A quick glance at car advertisements will reveal a rash of “100% loan” and “zero downpayment” slogans. The Straits Times has highlighted these tactics for years, but they have not been stamped out.

Stratospheric COE prices have a trickle-down effect on prices of other goods and services, contributing to overall cost of living.

While the premiums may continue to rise for the next quarter or two, the cyclical upswing in supply slated to start in 2024-25, could see some natural easing. But by then, premiums may have reached $150,000.

A multi-agency effort may be needed to arrest this trend again.