Streaming, CPF, Nantah: 7 difficult decisions that former president and DPM Tony Tan grappled with

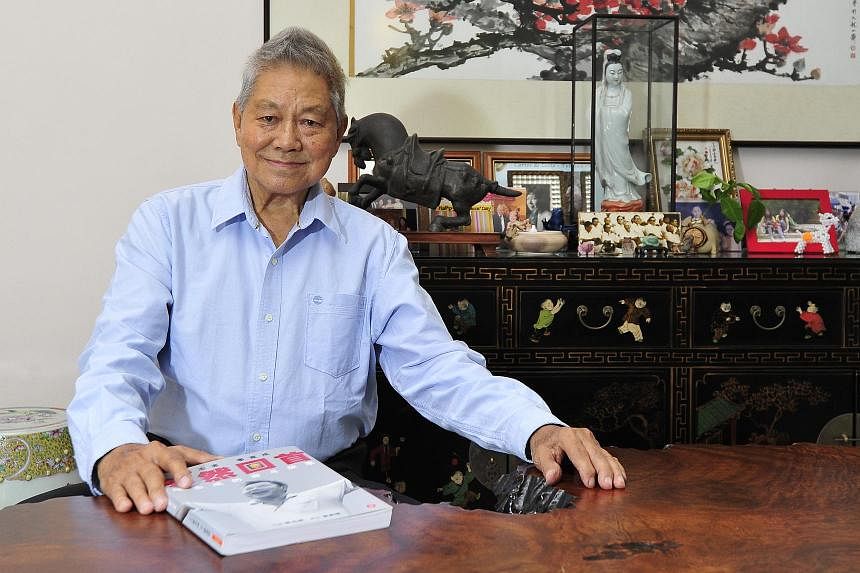

Dr Tony Tan shared how he sometimes had to go against decisions made by his predecessors – including those signed off by founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

Goh Yan Han

Political Correspondent

MAR 13, 2024

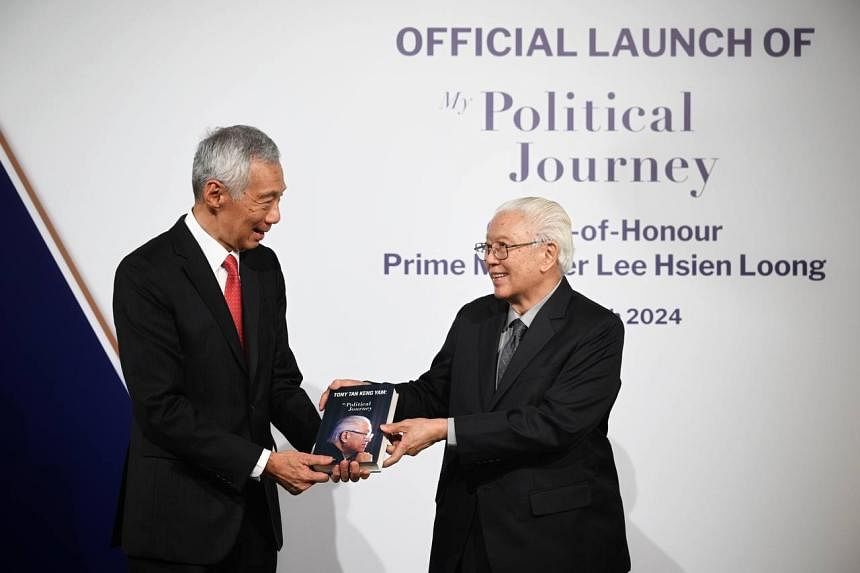

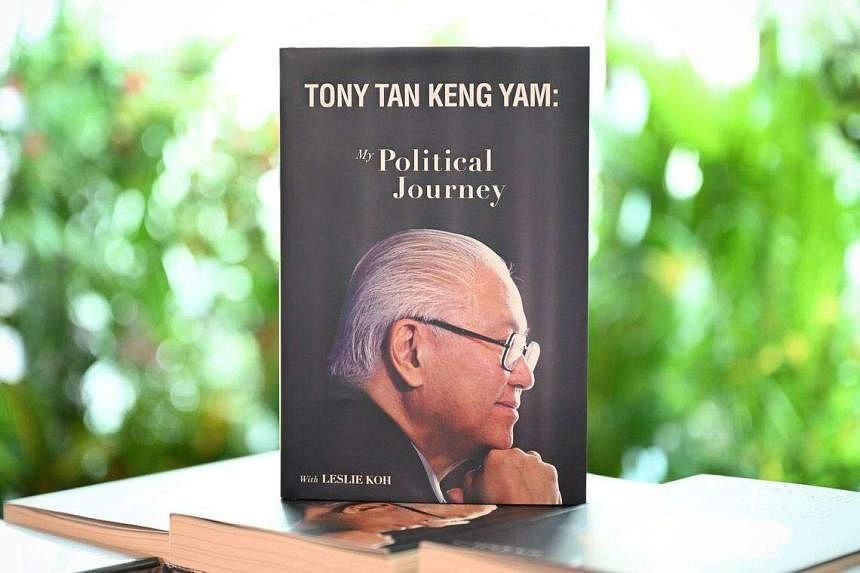

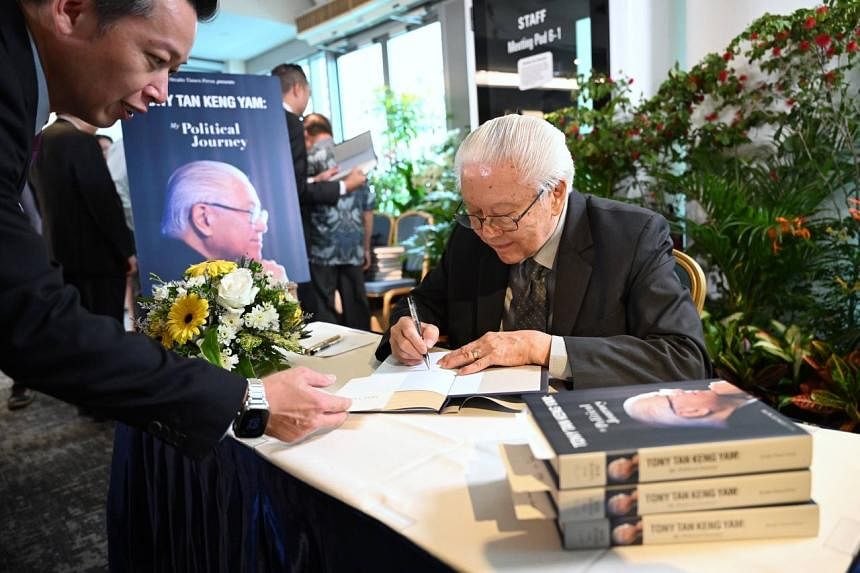

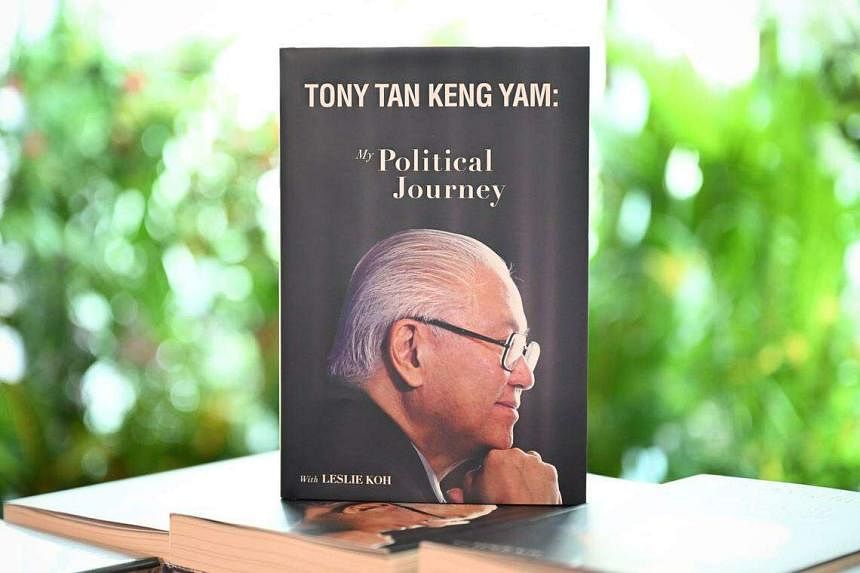

SINGAPORE – In a 340-page memoir, former president and deputy prime minister Tony Tan divulged the thinking behind some of the difficult policy decisions he had to make during his time in politics.

The book, titled Tony Tan Keng Yam: My Political Journey, was launched by publisher Straits Times Press on March 12. It is co-authored by Dr Tan and former ST journalist Leslie Koh.

In the book, the famously bespectacled statesman shared how he sometimes had to go against decisions made by his predecessors – including those signed off by founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew.

Here are seven that are highlighted in the book:

1. Entering politics, leaving and going back again

A mathematician who never was, Dr Tan had dreams of spending his life in academia or banking. He was certainly brainy: He topped his cohort at both the then equivalent versions of the O- and A-level exams, and graduated from university in two years.

In October 1978, he became OCBC Bank’s general manager, and his uncle, Tan Chin Tuan – also the bank’s chairman – was grooming him for greater things.

When the call came from then Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen to join the People’s Action Party, he was reluctant. But Mr Hon persisted in recommending Dr Tan to then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew.

“How could one say no to Mr Lee Kuan Yew?” said Dr Tan in his book.

In a meeting at the Istana with Mr Lee, Dr Tan tried to explain why he felt he was not suited for the job. But he felt like he did not have much of a choice, and in the end, he told Mr Lee: “I still don’t think I’m suited for the job, but if there’s a need, I’ll do it.”

This same hesitance popped up again in 1995, when Dr Tan received a call from then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong. Dr Tan had left Cabinet at the end of 1991 and returned to OCBC to become its chairman and CEO.

But Mr Goh needed someone to help strengthen the Cabinet as several veteran ministers had left.

“In the end, however, I felt there wasn’t much of a choice,” said Dr Tan of his return to politics. The interests of Singapore had to take precedence over that of the bank and his own personal considerations, he said.

The 340-page memoir, launched by publisher Straits Times Press, is co-authored by Dr Tony Tan and former ST journalist Leslie Koh. ST PHOTO: CHONG JUN LIANG

2. Introducing streaming

Difficult decisions abound in government – Dr Tan dedicated close to a quarter of his book to them – but his first one was to help introduce streaming in schools, in a major overhaul to Singapore’s education system.

The 1979 decision to implement streaming was proposed by then Education Minister Goh Keng Swee, who wanted to put students through different systems of education that would cater to varying abilities.

The names of the two streams were carefully chosen, said Dr Tan. The five-year course was “Normal” as students elsewhere were generally taking five years to complete their equivalent of secondary school. The four-year course was then named “Express”.

But when Dr Goh’s report was presented to Parliament, a heated debate ensued, with worries about the unintended effects of labelling, such as stigma.

Dr Goh eventually won over the MPs, but more importantly also the people. The lesson Dr Tan – who was then Senior Minister of State for Education – took was that communication is just as important as the policy itself.

Then Deputy Prime Minister and Education Minister Goh Keng Swee (second from right) at a Ministry of Education press conference in 1979. With him are (from left) Mr Herman Hochstadt, Mr Chai Chong Yii and Dr Tony Tan. PHOTO: ST FILE

Today, streaming is viewed as an outdated policy, reflected Dr Tan. The country

has shifted to subject-based banding.

Yet banding is a refinement of streaming: The fundamental idea is still to

teach students at a pace according to their ability, he said.

3. To close or to merge: The Nantah situation

Another challenging situation was falling enrolment at Nanyang University – fondly known by many as Nantah – and the difficulty its graduates had securing employment in the late 1970s.

Dr Tan sent Mr Lee a note, assessing three options. The first was to do nothing, while the second was to close down Nantah – both unfeasible options, he felt.

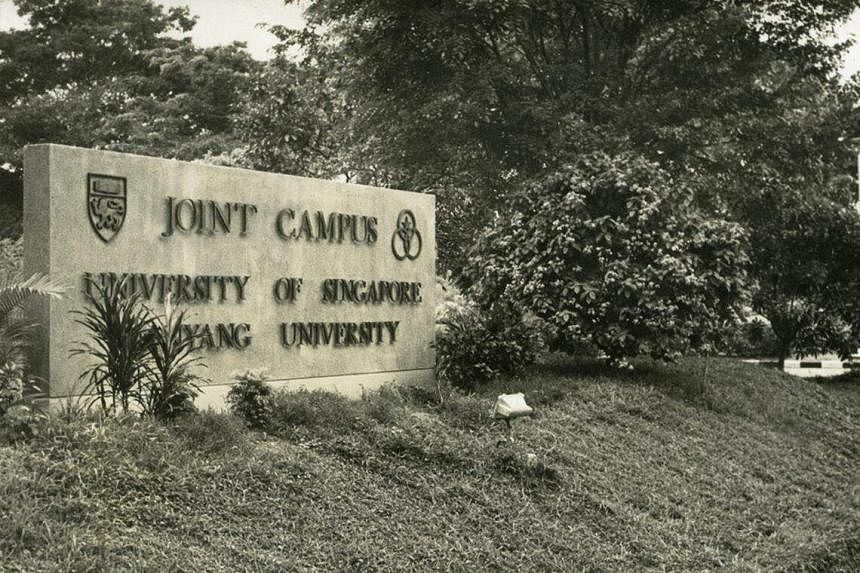

The only option was therefore to merge Nanyang University and the University of Singapore to form a new university.

“It was the only politically acceptable way of solving Nantah’s problems,” said Dr Tan. This would show that the Government was not favouring either university, nor closing down Nantah, which would give rise to accusations that the Government was anti-Chinese language education.

The merger was confirmed in 1980, and the National University of Singapore was formed, with Dr Tan as its first vice-chancellor.

In announcing the merger, Mr Lee promised the establishment of another university on the former Nantah grounds. The Government decided that for a start, the new university would have its degrees awarded by NUS so that it would not face the same enrolment and employability problems that Nantah had faced.

The merger of Nanyang University and the University of Singapore was confirmed in 1980. PHOTO: SPH FILE

The Nanyang Technological Institute was born in 1981, and 10 years later began issuing its own degrees.

Dr Tan believed that the merger was the right thing to do. “Some decisions are politically difficult. As I had learnt in the ministry, you can’t force people in education; you need time.”

4. Cutting CPF rates

In 1985, the economy took a sudden turn from rapid growth to an unexpected recession.

Singapore’s system of high Central Provident Fund contributions – which effectively took money out of the economy, and recirculated it into the system through the building and sale of Housing Board flats – was no longer working as HDB had suspended construction due to a surplus of flats.

This drained liquidity from the system and caused the economy to contract even though the world economy was still growing. It was clear that CPF rates had to be cut, said Dr Tan, who was then Minister of both Trade and Industry, and Finance.

But this was a knotty decision as Mr Lee had just said in his National Day Rally speech that year that the CPF rate should be kept at its current level to protect workers’ savings.

Despite worrying about contradicting Mr Lee, Dr Tan felt that it was his responsibility to publicly float the idea of a rate cut, and he did so at an annual dinner with civil service administrative officers.

In a Cabinet meeting soon after, where the issue was discussed, Dr Tan said Mr Lee did not push back. To his surprise, Mr Lee suggested a more substantive cut for a greater impact.

The CPF rate was eventually cut from 25 per cent to 10 per cent, alongside a host of stimulus measures to raise competitiveness.

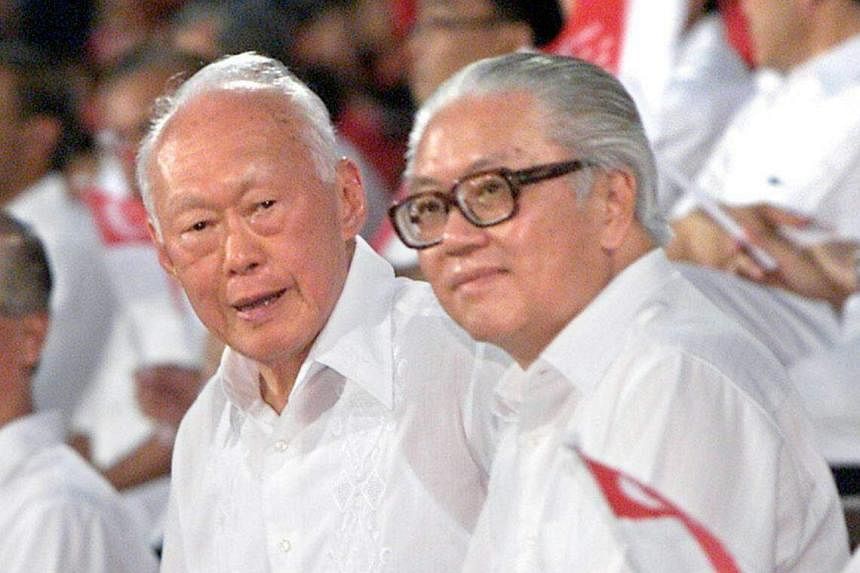

“It showed me how great a man Mr Lee was. Despite his own beliefs and convictions, he was never one to dismiss a counter-argument if it made sense,” said Dr Tan.

Mr Lee Kuan Yew and Dr Tan at the National Day Parade in 2003. PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO FILE

5. Scrapping the Graduate Mothers’ Scheme

In 1985, Dr Tan returned to helm the Education Ministry, though this time without his mentor, Dr Goh, to turn to for help and advice.

Right away, he decided on four major problems confronting the education system – one of which was the controversial Graduate Mothers’ Scheme.

The scheme gave graduate mothers with three or more children more priority in choosing schools for their children, and was criticised as discriminatory and an attempt at social engineering.

Data and feedback from teachers showed Dr Tan that the policy was not working, and he was convinced it should be scrapped. He met Mr Lee at lunch to tell him of the decision.

Mr Lee was very calm and said: “You’re the minister, you’re in charge... You must do what you think is right.”

The experience underscored to Dr Tan how government policies need constant review and updating. While they are usually introduced with good intentions, they may be the wrong policy for a changed circumstance, he said.

The Graduate Mothers’ Scheme gave graduate mothers with three or more children more priority in choosing schools for their children. PHOTO: ST FILE

6. Running for president

The 2011 presidential election was Singapore’s most hotly contested election to date as four men vied for the post and Dr Tan prevailed with a razor-thin margin.

Dr Tan was the last to publicly throw his hat into the ring, after former PAP MP Tan Cheng Bock, then NTUC Income chief Tan Kin Lian, and opposition politician Tan Jee Say had declared their intentions.

Former foreign minister George Yeo, who had lost in the general election that year, had emerged as a potential candidate at the time. While Mr Yeo would make a good president, Dr Tan wondered if he would prevail in a four-cornered race.

As he was then chairman of Singapore Press Holdings, Dr Tan asked reporters, based on ground sentiment, whether Mr Yeo or Dr Tan Cheng Bock would win.

The latter, they answered quickly, which alarmed him.

“We had three men running for president who didn’t seem to fully understand the role of the presidency, and the likelihood (was) that one of them would win,” he said.

After mulling over the issue for a few weeks, Dr Tan decided to put himself forward as a candidate despite having no great ambition to be the president and the risk of an ignominious end to his political life.

Sitting at his desk at the Istana the day after being sworn in, Dr Tan said he felt a great sense of relief.

Dr Tan being sworn in as Singapore’s seventh president and third elected president on Sept 1, 2011. PHOTO: ST FILE

7. Reserved presidency

Around 2016, while Dr Tan was president, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong broached the idea of the reserved presidency with him.

PM Lee wanted to find a way to ensure that the presidency does not become a “single-race office”, but that every race could be represented in the role at some point, said Dr Tan.

When Dr Tan first heard the proposal, he felt it was a sensible one as it would reflect the nation’s status as a multiracial country.

While as president, he could not take part in the House debate on the issue, he made clear his support for the change in a statement that was read out by the Speaker of Parliament.

The recommendation for the reserved presidency was a “balanced approach” that would ensure that Singapore would have a minority elected president from time to time, he wrote.

The long-term aspiration should be for minorities to be elected into the office without the need for any intervention, but one must recognise current realities, he noted then.

While President Tharman Shanmugaratnam

won the 2023 election with a landslide victory, Dr Tan believes it is too early to decide if Singapore can do away with the reserved presidency as race is too entrenched in a person’s make-up.

As such it would be premature to remove the legislation, and it is better to retain it in case it is needed in the future. The day may come that the reserved presidency is no longer needed – society is never static, said Dr Tan.