-

IP addresses are NOT logged in this forum so there's no point asking. Please note that this forum is full of homophobes, racists, lunatics, schizophrenics & absolute nut jobs with a smattering of geniuses, Chinese chauvinists, Moderate Muslims and last but not least a couple of "know-it-alls" constantly sprouting their dubious wisdom. If you believe that content generated by unsavory characters might cause you offense PLEASE LEAVE NOW! Sammyboy Admin and Staff are not responsible for your hurt feelings should you choose to read any of the content here. The OTHER forum is HERE so please stop asking.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

HERD IMMUNITY & VACCINATION SCIENTIFICALLY RULED OUT! Double Infection & REPEATED COVID INFECTIONS found EVERYWHERE

- Thread starter covid

- Start date

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2018

- Messages

- 31,528

- Points

- 113

That just means all locked downs be removed. Things back to normal as the populace needs to live with the virus. Dont let the virus rule your lifeMost will be OK a few won't be OK just like any other disease.

We don't lock down for flu which kills far more Singaporeans annually than Covid.

- Joined

- Aug 29, 2008

- Messages

- 27,499

- Points

- 113

Just let covid finish off those who have Neanderthal genes. Those guys' had ancestors who fucked sub human primates

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2018

- Messages

- 31,528

- Points

- 113

Coronavirus vaccine: what we know so far – a comprehensive guide by academic experts

M-Foto/Shutterstock

M-Foto/Shutterstock

Since the early days of the pandemic, attention has focused on producing a vaccine for COVID-19. With one, it’s hoped it will be able to suppress the virus without relying purely on economically challenging control measures. Without one, the world will probably have to live with COVID-19 as an endemic disease. It’s unlikely the coronavirus will naturally burn itself out.

With so much at stake, it’s not surprising that COVID-19 vaccines have become both a public and political obsession. The good news is that making one is possible: the virus has the right characteristics to be fended off with a vaccine, and the economic incentive exists to get one (or indeed several) developed.

But we need to be patient. Creating a new medicine requires a large amount of thought and scrutiny to make sure what’s produced is safe and effective. Researchers must be careful not to allow the pressure and allure of creating a vaccine quickly to undermine the integrity of their work. The upshot may be that we don’t have a highly effective vaccine against COVID-19 for some time.

Here, authors from across The Conversation outline what we know so far. Drawing upon their expertise, they explain how a COVID-19 vaccine will work, the progress a leading vaccine (developed by the University of Oxford with AstraZeneca) is making, and what challenges there will be to manufacturing and rolling a vaccine out when ready.

How will vaccines work for COVID-19?

Producing the spike protein

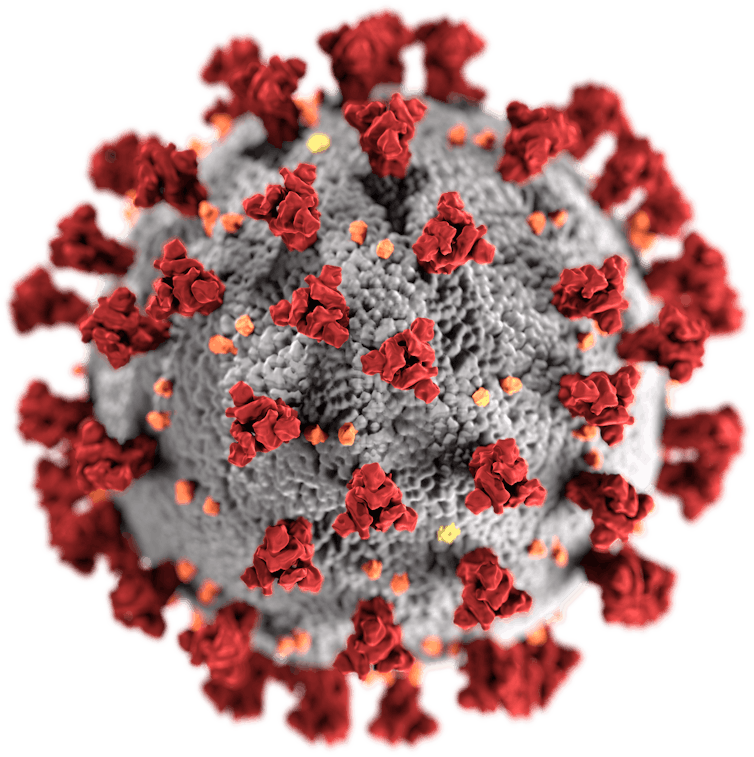

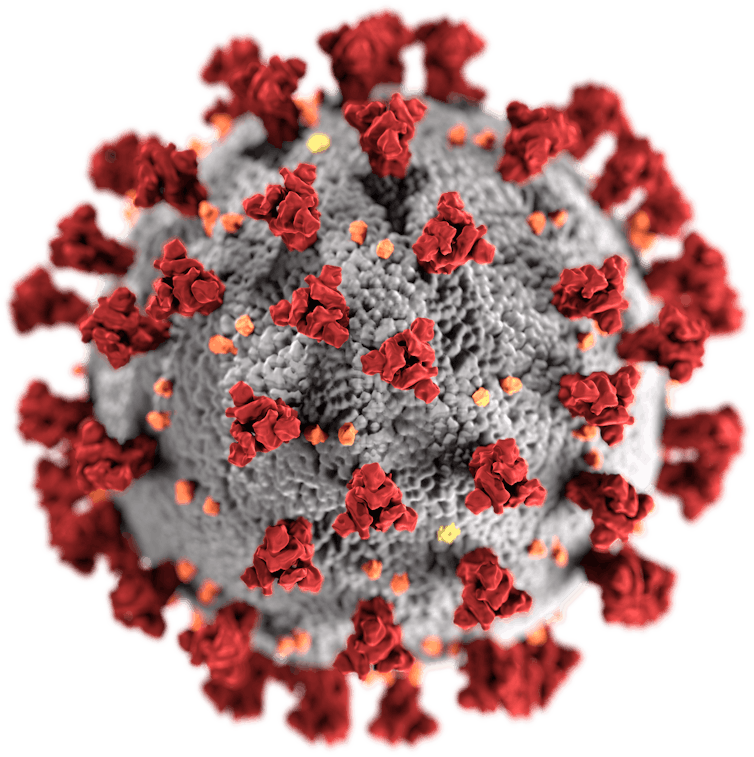

Although the way the body interacts with SARS-CoV-2 isn’t fully understood, there’s one particular part of the virus that’s thought to trigger an immune response – the spike protein, which sticks up on the virus’s surface. Therefore, the two leading COVID-19 vaccines both focus on getting the body to produce these key spike proteins, to train the immune system to recognise them and destroy any viral particles that exhibit them in the future.

SARS-CoV-2, with its spike proteins shown in red.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Wikimedia Commons

SARS-CoV-2, with its spike proteins shown in red.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Wikimedia Commons

The pros and cons of different designs

The leading vaccines both work by delivering a piece of the coronavirus’s genetic material into cells, which instructs the cell to make copies of the spike protein. As Suresh Mahalingam and Adam Taylor explain, one (Moderna’s) makes the delivery using a molecule called messenger RNA, the other (AstraZeneca’s) using a harmless adenovirus. These cutting-edge vaccine designs have their pros and cons, as do traditional methods.

Boosters may be needed

The strongest immune responses, says Sarah Pitt, come from vaccines that contain a live version of what they’re trying to protect against. Because there’s so much we don’t know about SARS-CoV-2, putting a live version of the virus into a vaccine can be risky. Safer methods – such as getting the body to make just the virus’s spike proteins, or delivering a dead version of the virus – will lead to a weaker response that fades over time. But boosters can top this up.

if boosters are required, manufacturing sufficient doses and delivering them will become an even greater challenge. SiphiIwe Sibeko/EPA

if boosters are required, manufacturing sufficient doses and delivering them will become an even greater challenge. SiphiIwe Sibeko/EPA

What governs how we respond to vaccines?

A vaccine’s design isn’t the only factor that determines how strong our immune response is. As Menno van Zelm and Paul Gill show, there are four other variables that make each person’s response to a vaccine unique: their age, their genes, lifestyle factors and what previous infections they have been exposed to. It may be that not everyone gets long-lasting immunity from a vaccine.

Why vaccines provide strong immunity

If well-designed, a vaccine can provide better immunity than natural infection, says Maitreyi Shivkumar. This is because vaccines can focus the immune system on targeting recognisable parts of the pathogen (for example the spike protein), can kickstart a stronger response using ingredients called adjuvants, and can be delivered to key parts of the body where an immune response is needed most. For COVID-19, this could be the nose.

Nasally delivered vaccines are already in use for some diseases, such as flu.Douglas Jordan, MA/CDC

Nasally delivered vaccines are already in use for some diseases, such as flu.Douglas Jordan, MA/CDC

How to use a vaccine when it’s available

Scientists think between 50% and 70% of people need to be resistant to the coronavirus to stop it spreading. Using a vaccine to rapidly make that many people immune might be difficult, says Adam Kleczkowski. Vaccines are rarely 100% effective, and hesitancy and potential side effects may make a quick, mass roll-out unrealistic. A better strategy might be to target people most at risk together with those likely to infect many others.

How is the Oxford vaccine being developed, tested and approved?

The many steps of vaccine development

Vaccine development is quicker now than it ever has been, explain Samantha Vanderslott, Andrew Pollard and Tonia Thomas. Researchers can use knowledge from previous vaccines, and in an outbreak more resources are made available. Nevertheless, it’s still a lengthy process, involving research on the virus, testing in animals and clinical trials in humans. Once approved, millions of doses then need to be produced.

Phase 1 and phase 2 trials are successful

After showing promise in animals, the University of Oxford’s vaccine moved onto human testing – known as clinical trials, which are split into three phases. Here, Rebecca Ashfield outlines the joint phase 1 and 2 trial that the vaccine passed through to check that it was safe and elicited an immune response, and explains how the vaccine actually uses a separate virus – a chimpanzee adenovirus – to deliver its content into cells.

Production of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine in Latin America is taking place in Argentina; part of the phase 3 trial is being run in Brazil. EPA-EFE

Production of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine in Latin America is taking place in Argentina; part of the phase 3 trial is being run in Brazil. EPA-EFE

How the phase 3 trial works

Earlier trial phases showed that the vaccine stimulated the immune system, as expected. But the million-dollar question is whether this actually protects against COVID-19. Finding out means giving the vaccine to thousands of people who might be exposed to the coronavirus and seeing whether they get sick. As Ashfield and Pedro Folegatti show, this requires running vaccination programmes in countries across the world.

Testing was paused – and that’s OK

In September, the phase 3 trial of the Oxford vaccine was paused after a patient fell ill with a possible adverse reaction. Understandably this caused dismay, but it shouldn’t have, says Simon Kolstoe. Pauses like this are common, as independent moderators are needed to assess exactly what has happened. Often illnesses in trials are unrelated to what’s being tested. But even if they are, that’s exactly what we want these tests to show.

In the US arm of the trial, one-third of participants are receiving a saline injection as a control.DonyaHHI/Shutterstock

In the US arm of the trial, one-third of participants are receiving a saline injection as a control.DonyaHHI/Shutterstock

But vaccine makers need to be more open

AstraZeneca didn’t publicly reveal what caused the pause but did share this information with investors. This, says Duncan Matthews, was an example of an attempt to apply old methods of operating to a new situation.

Why we need to know what’s in placebos

A key part of clinical trials are placebos – alternative or inactive treatments that are given to participants for comparison. But a key problem, Jeremy Howick explains, is that some vaccine trials don’t reveal what their placebos contain. Without knowing what benchmark is being used, it’s then difficult for outsiders to understand the relative effect (and side effects) the vaccine has.

How will the vaccine be made and rolled out?

Preparing enough for the whole world

Universal demand for a COVID-19 vaccine means production bottlenecks are a risk. For the Oxford vaccine, production involves growing key components in human embryonic kidney cells, before creating the actual vaccine and then purifying and then concentrating it. Running this process at industrial scale, say Qasim Rafiq and Martina Micheletti, is one of the biggest challenges AstraZeneca faces.

AstraZeneca and its partners are aiming to manufacture 2 billion doses of its vaccine by the end of 2021.RGtimeline/Shutterstock

AstraZeneca and its partners are aiming to manufacture 2 billion doses of its vaccine by the end of 2021.RGtimeline/Shutterstock

Tobacco – an unexpected ally?

Vaccines contain organic products, which traditionally have been grown using cell cultures in containers called bioreactors. Recently plants have been adapted to function as bioreactors too, which could help production be massively increased. Tobacco may be especially useful: it grows quickly, is farmed all over the world, is leafy and easily modifiable. The tech hasn’t been approved for mass producing medicines – but demand may change that.

Keeping vaccines cool will be crucial

Because COVID-19 vaccines will contain biological material, they’ll need to be kept cold right up until they’re delivered, explains Anna Nagurney. Fail to keep them cool and they’ll become ineffective. Refrigeration will therefore be a major challenge in any roll-out campaign; an estimated 25% of vaccines are spoiled by the time they reach their destination. A potential solution could be to encase their heat-sensitive parts in silica.

Cold storage facilities will be needed to store vaccines, while refrigerated trucks and planes will be needed to move them.Tony Karumba/AFP via Getty Images

Cold storage facilities will be needed to store vaccines, while refrigerated trucks and planes will be needed to move them.Tony Karumba/AFP via Getty Images

‘Vaccine nationalism’ threatens universal access

Some governments are signing agreements with manufacturers to supply them with vaccines ahead of other countries. Poorer nations risk being left empty handed – putting people at risk and preventing any attempt to coordinate suppressing the coronavirus worldwide. It’s also unclear how access is being priced in these deals.

How to counter vaccine nationalism

India can play a key role in avoiding this “richest-takes-all” scenario, says Rory Horner. It’s traditionally been a major supplier of medicines to the global south, and has the capacity to create more vaccines for COVID-19 than any other country in the world. India’s Serum Institute has signed up to make 400 million doses of the Oxford vaccine this year, but with a population of 1.35 billion, how many will go abroad isn’t yet clear.

India’s track record in producing vaccines and key medical ingredients has led to it being labelled the ‘pharmacy of the world’.Shutterstock/ManoejPaateel

India’s track record in producing vaccines and key medical ingredients has led to it being labelled the ‘pharmacy of the world’.Shutterstock/ManoejPaateel

Who will get the coronavirus vaccine first?

We need to plan now, say Laurence Roope and Philip Clarke. Governments have big decisions to make. The pandemic is akin to a war situation, so there’s an argument these vital goods should be rationed and banned from private sale. Authorities also need to decide who should be prioritised: those most vulnerable, people most likely to spread the virus, or those who can kickstart the economy by returning to work.

How do you counter resistance and scepticism?

Public resistance is a sizeable problem – but nothing new

Surveys show that one in four New Zealanders remain hesitant about a coronavirus vaccine, while one in six British people would refuse one. But vaccine hesitancy has been around for a long time, writes Sally Frampton. And Steven King argues the past – such as when smallpox vaccines were resisted – may provide some solutions to this problem.

Are anti-vaxxers a problem?

Not all hesitancy is the same, says Annamaria Carusi. As well as the hardcore anti-vaxxers, plenty may resist COVID-19 vaccines on safety or animal welfare grounds. Indeed, while anti-vaxxers attract a lot of attention, their influence on vaccination rates is often overstated, argues Samantha Vanderslott. In fact, desire for a vaccine is so widespread and strong that anti-vaxxer positions may be harder to defend right now.

Resistance to a COVID-19 vaccine has been well-documented – but there is also overwhelming anticipation. EPA-EFE

Resistance to a COVID-19 vaccine has been well-documented – but there is also overwhelming anticipation. EPA-EFE

The far right is exploiting the pandemic

A recent report from the United Nations Security Council warned that extreme right-wing groups in the US are using the pandemic to “radicalise, recruit, and inspire plots and attacks”. Blyth Crawford gives a run-down of the major groups at work in America – what their aims are, the methods they’re using to reach people, and the key pieces of misinformation that they’re peddling.

How to build trust in vaccines

The usual strategy is to double down on positive messaging. But a better strategy, Mark Honigsbaum argues, would be to acknowledge that there’s a lot we don’t know about how some vaccines work, but that the benefits of taking vaccines far outweigh the risks. A further step could be to make sure that manufacturers are liable should vaccine recipients suffer negative effects. Often manufacturers are exempt.

Looking ahead

The future is full of possibility. COVID-19, Sars, Mers and the common cold are all caused by coronaviruses, and scientists are considering whether it’s possible to create a vaccine that could offer protection against them all – and perhaps even against an as yet unknown coronavirus we’re yet to encounter. Admittedly, having a vaccine that can do this seems unlikely in the near future.

We shouldn’t get ahead of ourselves, though, says Sarah Pitt. No vaccine has yet completed its safety trials, and we can’t yet be sure that any vaccine will permanently prevent people from catching COVID-19. We need to prepare ourselves for the very real possibility that a COVID-19 vaccine only reduces the severity of symptoms or provides temporary protection.

Since the early days of the pandemic, attention has focused on producing a vaccine for COVID-19. With one, it’s hoped it will be able to suppress the virus without relying purely on economically challenging control measures. Without one, the world will probably have to live with COVID-19 as an endemic disease. It’s unlikely the coronavirus will naturally burn itself out.

With so much at stake, it’s not surprising that COVID-19 vaccines have become both a public and political obsession. The good news is that making one is possible: the virus has the right characteristics to be fended off with a vaccine, and the economic incentive exists to get one (or indeed several) developed.

But we need to be patient. Creating a new medicine requires a large amount of thought and scrutiny to make sure what’s produced is safe and effective. Researchers must be careful not to allow the pressure and allure of creating a vaccine quickly to undermine the integrity of their work. The upshot may be that we don’t have a highly effective vaccine against COVID-19 for some time.

Here, authors from across The Conversation outline what we know so far. Drawing upon their expertise, they explain how a COVID-19 vaccine will work, the progress a leading vaccine (developed by the University of Oxford with AstraZeneca) is making, and what challenges there will be to manufacturing and rolling a vaccine out when ready.

How will vaccines work for COVID-19?

Producing the spike protein

Although the way the body interacts with SARS-CoV-2 isn’t fully understood, there’s one particular part of the virus that’s thought to trigger an immune response – the spike protein, which sticks up on the virus’s surface. Therefore, the two leading COVID-19 vaccines both focus on getting the body to produce these key spike proteins, to train the immune system to recognise them and destroy any viral particles that exhibit them in the future.

The pros and cons of different designs

The leading vaccines both work by delivering a piece of the coronavirus’s genetic material into cells, which instructs the cell to make copies of the spike protein. As Suresh Mahalingam and Adam Taylor explain, one (Moderna’s) makes the delivery using a molecule called messenger RNA, the other (AstraZeneca’s) using a harmless adenovirus. These cutting-edge vaccine designs have their pros and cons, as do traditional methods.

Boosters may be needed

The strongest immune responses, says Sarah Pitt, come from vaccines that contain a live version of what they’re trying to protect against. Because there’s so much we don’t know about SARS-CoV-2, putting a live version of the virus into a vaccine can be risky. Safer methods – such as getting the body to make just the virus’s spike proteins, or delivering a dead version of the virus – will lead to a weaker response that fades over time. But boosters can top this up.

What governs how we respond to vaccines?

A vaccine’s design isn’t the only factor that determines how strong our immune response is. As Menno van Zelm and Paul Gill show, there are four other variables that make each person’s response to a vaccine unique: their age, their genes, lifestyle factors and what previous infections they have been exposed to. It may be that not everyone gets long-lasting immunity from a vaccine.

Why vaccines provide strong immunity

If well-designed, a vaccine can provide better immunity than natural infection, says Maitreyi Shivkumar. This is because vaccines can focus the immune system on targeting recognisable parts of the pathogen (for example the spike protein), can kickstart a stronger response using ingredients called adjuvants, and can be delivered to key parts of the body where an immune response is needed most. For COVID-19, this could be the nose.

How to use a vaccine when it’s available

Scientists think between 50% and 70% of people need to be resistant to the coronavirus to stop it spreading. Using a vaccine to rapidly make that many people immune might be difficult, says Adam Kleczkowski. Vaccines are rarely 100% effective, and hesitancy and potential side effects may make a quick, mass roll-out unrealistic. A better strategy might be to target people most at risk together with those likely to infect many others.

How is the Oxford vaccine being developed, tested and approved?

The many steps of vaccine development

Vaccine development is quicker now than it ever has been, explain Samantha Vanderslott, Andrew Pollard and Tonia Thomas. Researchers can use knowledge from previous vaccines, and in an outbreak more resources are made available. Nevertheless, it’s still a lengthy process, involving research on the virus, testing in animals and clinical trials in humans. Once approved, millions of doses then need to be produced.

Phase 1 and phase 2 trials are successful

After showing promise in animals, the University of Oxford’s vaccine moved onto human testing – known as clinical trials, which are split into three phases. Here, Rebecca Ashfield outlines the joint phase 1 and 2 trial that the vaccine passed through to check that it was safe and elicited an immune response, and explains how the vaccine actually uses a separate virus – a chimpanzee adenovirus – to deliver its content into cells.

How the phase 3 trial works

Earlier trial phases showed that the vaccine stimulated the immune system, as expected. But the million-dollar question is whether this actually protects against COVID-19. Finding out means giving the vaccine to thousands of people who might be exposed to the coronavirus and seeing whether they get sick. As Ashfield and Pedro Folegatti show, this requires running vaccination programmes in countries across the world.

Testing was paused – and that’s OK

In September, the phase 3 trial of the Oxford vaccine was paused after a patient fell ill with a possible adverse reaction. Understandably this caused dismay, but it shouldn’t have, says Simon Kolstoe. Pauses like this are common, as independent moderators are needed to assess exactly what has happened. Often illnesses in trials are unrelated to what’s being tested. But even if they are, that’s exactly what we want these tests to show.

But vaccine makers need to be more open

AstraZeneca didn’t publicly reveal what caused the pause but did share this information with investors. This, says Duncan Matthews, was an example of an attempt to apply old methods of operating to a new situation.

Why we need to know what’s in placebos

A key part of clinical trials are placebos – alternative or inactive treatments that are given to participants for comparison. But a key problem, Jeremy Howick explains, is that some vaccine trials don’t reveal what their placebos contain. Without knowing what benchmark is being used, it’s then difficult for outsiders to understand the relative effect (and side effects) the vaccine has.

How will the vaccine be made and rolled out?

Preparing enough for the whole world

Universal demand for a COVID-19 vaccine means production bottlenecks are a risk. For the Oxford vaccine, production involves growing key components in human embryonic kidney cells, before creating the actual vaccine and then purifying and then concentrating it. Running this process at industrial scale, say Qasim Rafiq and Martina Micheletti, is one of the biggest challenges AstraZeneca faces.

Tobacco – an unexpected ally?

Vaccines contain organic products, which traditionally have been grown using cell cultures in containers called bioreactors. Recently plants have been adapted to function as bioreactors too, which could help production be massively increased. Tobacco may be especially useful: it grows quickly, is farmed all over the world, is leafy and easily modifiable. The tech hasn’t been approved for mass producing medicines – but demand may change that.

Keeping vaccines cool will be crucial

Because COVID-19 vaccines will contain biological material, they’ll need to be kept cold right up until they’re delivered, explains Anna Nagurney. Fail to keep them cool and they’ll become ineffective. Refrigeration will therefore be a major challenge in any roll-out campaign; an estimated 25% of vaccines are spoiled by the time they reach their destination. A potential solution could be to encase their heat-sensitive parts in silica.

‘Vaccine nationalism’ threatens universal access

Some governments are signing agreements with manufacturers to supply them with vaccines ahead of other countries. Poorer nations risk being left empty handed – putting people at risk and preventing any attempt to coordinate suppressing the coronavirus worldwide. It’s also unclear how access is being priced in these deals.

How to counter vaccine nationalism

India can play a key role in avoiding this “richest-takes-all” scenario, says Rory Horner. It’s traditionally been a major supplier of medicines to the global south, and has the capacity to create more vaccines for COVID-19 than any other country in the world. India’s Serum Institute has signed up to make 400 million doses of the Oxford vaccine this year, but with a population of 1.35 billion, how many will go abroad isn’t yet clear.

Who will get the coronavirus vaccine first?

We need to plan now, say Laurence Roope and Philip Clarke. Governments have big decisions to make. The pandemic is akin to a war situation, so there’s an argument these vital goods should be rationed and banned from private sale. Authorities also need to decide who should be prioritised: those most vulnerable, people most likely to spread the virus, or those who can kickstart the economy by returning to work.

How do you counter resistance and scepticism?

Public resistance is a sizeable problem – but nothing new

Surveys show that one in four New Zealanders remain hesitant about a coronavirus vaccine, while one in six British people would refuse one. But vaccine hesitancy has been around for a long time, writes Sally Frampton. And Steven King argues the past – such as when smallpox vaccines were resisted – may provide some solutions to this problem.

Are anti-vaxxers a problem?

Not all hesitancy is the same, says Annamaria Carusi. As well as the hardcore anti-vaxxers, plenty may resist COVID-19 vaccines on safety or animal welfare grounds. Indeed, while anti-vaxxers attract a lot of attention, their influence on vaccination rates is often overstated, argues Samantha Vanderslott. In fact, desire for a vaccine is so widespread and strong that anti-vaxxer positions may be harder to defend right now.

The far right is exploiting the pandemic

A recent report from the United Nations Security Council warned that extreme right-wing groups in the US are using the pandemic to “radicalise, recruit, and inspire plots and attacks”. Blyth Crawford gives a run-down of the major groups at work in America – what their aims are, the methods they’re using to reach people, and the key pieces of misinformation that they’re peddling.

How to build trust in vaccines

The usual strategy is to double down on positive messaging. But a better strategy, Mark Honigsbaum argues, would be to acknowledge that there’s a lot we don’t know about how some vaccines work, but that the benefits of taking vaccines far outweigh the risks. A further step could be to make sure that manufacturers are liable should vaccine recipients suffer negative effects. Often manufacturers are exempt.

Looking ahead

The future is full of possibility. COVID-19, Sars, Mers and the common cold are all caused by coronaviruses, and scientists are considering whether it’s possible to create a vaccine that could offer protection against them all – and perhaps even against an as yet unknown coronavirus we’re yet to encounter. Admittedly, having a vaccine that can do this seems unlikely in the near future.

We shouldn’t get ahead of ourselves, though, says Sarah Pitt. No vaccine has yet completed its safety trials, and we can’t yet be sure that any vaccine will permanently prevent people from catching COVID-19. We need to prepare ourselves for the very real possibility that a COVID-19 vaccine only reduces the severity of symptoms or provides temporary protection.

- Joined

- Jul 9, 2011

- Messages

- 2,759

- Points

- 48

Cheers to COVID VIRUS!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

COVID! COVID! COVID!

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2018

- Messages

- 31,528

- Points

- 113

Long Covid: what we know so far | Coronavirus

Many Covid sufferers have reported lasting fatigue and breathlessness. Photograph: Pablo Blázquez Domínguez/Getty Images

Many Covid sufferers have reported lasting fatigue and breathlessness. Photograph: Pablo Blázquez Domínguez/Getty Images

Lasting symptoms may not be down to a single syndrome but several different ones

Thu 15 Oct 2020 16.01 AEDT

At the start of the pandemic we were told that Covid-19 was a respiratory illness from which most people would recover within two or three weeks, but it’s increasingly clear that there may be tens of thousands of people, if not hundreds of thousands, who have been left experiencing symptoms months after becoming infected.

Now, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has released a report which suggests that “long Covid” may not be a single syndrome, but up to four different ones, which some patients might be experiencing simultaneously. Here’s what we now know:

Variety of symptoms

Subtypes of lasting Covid identified by the NIHR included patients experiencing the after-effects of intensive care; those with post-viral fatigue; people with lasting organ damage; and those with fluctuating symptoms that move around the body.

“We believe that the term long Covid is being used as a catch-all for more than one syndrome, possibly up to four, and that the lack of distinction between these syndromes may explain the challenges people are having in being believed and accessing services,” said Dr Elaine Maxwell, the lead author of the report, which drew upon the experiences of patients and the latest published research. However, Prof Danny Altmann, an immunologist at Imperial College London, cautioned that narrowing long Covid down to just four syndromes might be too simplistic.

Recovering from ICU

Hospital discharge is often only the start of a lengthy recovery process. Many Covid-19 patients who have survived a period in intensive care are too weak to sit unaided or lift their arms off the bed, and some may even struggle to speak or swallow. They may also be affected by depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. However, severe lasting symptoms were not restricted to this group.

Post-viral fatigue

Many Covid “long-haulers” report fatigue, aching muscles and difficulty concentrating. The extent to which this overlaps with chronic fatigue syndrome is being investigated. CFS has previously been linked to infection with Epstein-Barr virus and Q fever. Studies of people who were infected during the 2003 Sars outbreak have also indicated that around a third of them had a reduced tolerance of exercise for many months, despite their lungs appearing healthy.

Lasting organ damage

Ongoing breathlessness, coughs, or a racing pulse could be symptoms of lasting damage to the lungs or heart, although this isn’t necessarily permanent. Lung damage seems particularly prevalent among patients who required hospital treatment for Covid-19. A recent study found that six weeks after leaving hospital, around half of patients were still experiencing breathlessness, dropping to 39% at 12 weeks. Meanwhile, approximately a third of hospitalised patients sustain heart damage, but those with seemingly mild infections can also be affected.

A separate study of 100 patients, many of whom had relatively mild symptoms when they were infected in March, revealed that 78 of them showed abnormal structural changes to their hearts on an MRI scan. These changes didn’t necessarily cause symptoms, and may dissipate with time, however. Ongoing problems with the liver and skin have also been reported.

Symptoms that fluctuate and move around body

Perhaps the weirdest group of Covid long-haulers are those with fluctuating symptoms. A common theme is that symptoms arise in one physiological system then abate, only for symptoms to arise in a different system, the NIHR report said. This fits with the results of a survey of long Covid support group members which found that 70% experienced fluctuations in the type of symptoms, and 89% in the intensity of their symptoms. Although the underlying mechanism remains unproven, such symptoms might fit with a disrupted immune system, Altmann said.

All ages affected

Estimates have suggested that 10% of Covid patients experience symptoms lasting longer than three weeks, and around one in 50 will still be ill at three months. The NIHR report said lasting symptoms had been observed in all age groups, including children, but unpublished results from the Covid Symptom Study suggest that women and older people may be at greater risk. “Above the age of 18, the risk of symptoms lasting for longer than a month seems to generally increase with age,” said Prof Tim Spector, a professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College London who runs the study.

A particularly under-studied group are elderly care home residents. “What we’ve been hearing from frontline staff is that there’s a group of patients who maybe looked like they were recovering, and then had a relapse,” said Prof Karen Spilsbury, chair in nursing research at the University of Leeds, who has been studying the impact of Covid-19 on care home residents. Their strength and stamina seemed to suffer, while Covid may have accelerated the rate of cognitive decline in those with dementia.

Topics

Lasting symptoms may not be down to a single syndrome but several different ones

Thu 15 Oct 2020 16.01 AEDT

At the start of the pandemic we were told that Covid-19 was a respiratory illness from which most people would recover within two or three weeks, but it’s increasingly clear that there may be tens of thousands of people, if not hundreds of thousands, who have been left experiencing symptoms months after becoming infected.

Now, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has released a report which suggests that “long Covid” may not be a single syndrome, but up to four different ones, which some patients might be experiencing simultaneously. Here’s what we now know:

Variety of symptoms

Subtypes of lasting Covid identified by the NIHR included patients experiencing the after-effects of intensive care; those with post-viral fatigue; people with lasting organ damage; and those with fluctuating symptoms that move around the body.

“We believe that the term long Covid is being used as a catch-all for more than one syndrome, possibly up to four, and that the lack of distinction between these syndromes may explain the challenges people are having in being believed and accessing services,” said Dr Elaine Maxwell, the lead author of the report, which drew upon the experiences of patients and the latest published research. However, Prof Danny Altmann, an immunologist at Imperial College London, cautioned that narrowing long Covid down to just four syndromes might be too simplistic.

Recovering from ICU

Hospital discharge is often only the start of a lengthy recovery process. Many Covid-19 patients who have survived a period in intensive care are too weak to sit unaided or lift their arms off the bed, and some may even struggle to speak or swallow. They may also be affected by depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. However, severe lasting symptoms were not restricted to this group.

Post-viral fatigue

Many Covid “long-haulers” report fatigue, aching muscles and difficulty concentrating. The extent to which this overlaps with chronic fatigue syndrome is being investigated. CFS has previously been linked to infection with Epstein-Barr virus and Q fever. Studies of people who were infected during the 2003 Sars outbreak have also indicated that around a third of them had a reduced tolerance of exercise for many months, despite their lungs appearing healthy.

Lasting organ damage

Ongoing breathlessness, coughs, or a racing pulse could be symptoms of lasting damage to the lungs or heart, although this isn’t necessarily permanent. Lung damage seems particularly prevalent among patients who required hospital treatment for Covid-19. A recent study found that six weeks after leaving hospital, around half of patients were still experiencing breathlessness, dropping to 39% at 12 weeks. Meanwhile, approximately a third of hospitalised patients sustain heart damage, but those with seemingly mild infections can also be affected.

A separate study of 100 patients, many of whom had relatively mild symptoms when they were infected in March, revealed that 78 of them showed abnormal structural changes to their hearts on an MRI scan. These changes didn’t necessarily cause symptoms, and may dissipate with time, however. Ongoing problems with the liver and skin have also been reported.

Symptoms that fluctuate and move around body

Perhaps the weirdest group of Covid long-haulers are those with fluctuating symptoms. A common theme is that symptoms arise in one physiological system then abate, only for symptoms to arise in a different system, the NIHR report said. This fits with the results of a survey of long Covid support group members which found that 70% experienced fluctuations in the type of symptoms, and 89% in the intensity of their symptoms. Although the underlying mechanism remains unproven, such symptoms might fit with a disrupted immune system, Altmann said.

All ages affected

Estimates have suggested that 10% of Covid patients experience symptoms lasting longer than three weeks, and around one in 50 will still be ill at three months. The NIHR report said lasting symptoms had been observed in all age groups, including children, but unpublished results from the Covid Symptom Study suggest that women and older people may be at greater risk. “Above the age of 18, the risk of symptoms lasting for longer than a month seems to generally increase with age,” said Prof Tim Spector, a professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College London who runs the study.

A particularly under-studied group are elderly care home residents. “What we’ve been hearing from frontline staff is that there’s a group of patients who maybe looked like they were recovering, and then had a relapse,” said Prof Karen Spilsbury, chair in nursing research at the University of Leeds, who has been studying the impact of Covid-19 on care home residents. Their strength and stamina seemed to suffer, while Covid may have accelerated the rate of cognitive decline in those with dementia.

Topics

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2018

- Messages

- 31,528

- Points

- 113

Ang mor lands have lost out to ah tiong vaccine...

Covid-19 vaccine candidate from China’s CNBG shows promise in human test, study shows | Malay Mail

A booth displaying a coronavirus vaccine candidate from China National Biotec Group (CNBG), is seen at the 2020 China International Fair for Trade in Services (CIFTIS), following the Covid-19 outbreak, in Beijing, China September 4, 2020. — Reuters pic

A booth displaying a coronavirus vaccine candidate from China National Biotec Group (CNBG), is seen at the 2020 China International Fair for Trade in Services (CIFTIS), following the Covid-19 outbreak, in Beijing, China September 4, 2020. — Reuters pic

BEIJING, Oct 16 — One of China’s front-running coronavirus vaccine candidates was shown to be safe and triggered immune responses in a combined early and mid-stage test in humans, researchers said.

The potential vaccine, dubbed BBIBP-CorV, is being developed by the Beijing Institute of Biological Products, a subsidiary of China National Biotec Group (CNBG).

It has already been approved for an emergency inoculation programme in China targeting essential workers and other limited groups of people facing high infection risk.

However, whether the shot can safely protect people from the Covid-19 disease that has killed more than one million people worldwide will only become clear when final Phase III trials — which are ongoing outside China — are complete.

BBIBP-CorV is one of at least 10 coronavirus vaccine projects globally to have entered Phase III trials, four of which are led by Chinese scientists, according to the World Health Organization.

It did not cause any severe side effects, while common mild or moderate adverse reactions included fever and pain in injection sites, according to a paper published yesterday in medical journal the Lancet.

The results came from a combined Phase I and Phase II trial involving more than 600 healthy adults conducted between April 29 and July 30.

Two injections of BBIBP-CorV at three different doses generated antibodies in all recipients of each group, including older participants, although the data does not prove the vaccine is efficacious, researchers at the CNBG subsidiary, Chinese disease control authorities and other research institutes said in the paper.

Antibody levels in recipients aged 60 and above were lower and took longer to increase significantly than those in younger participants, the results showed.

The study did not discuss whether the shot could elicit and maintain cell-based immune responses, another important weapon of the human immune system, which could be crucial if antibody-based immunity alone cannot stave off the virus.

Apart from BBIBP-CorV, CNBG, a unit of state-owned China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm), has another similar candidate developed by a different subsidiary which is also being tested overseas in Phase III trials and used in China’s emergency use programme.

A CNBG executive said last month the two candidates could potentially obtain conditional approval for use in the general public this year.

The other candidate by CNBG also induced antibodies without causing serious side effects in early and mid-stage trials, a research paper showed in August. — Reuters

Covid-19 vaccine candidate from China’s CNBG shows promise in human test, study shows | Malay Mail

BEIJING, Oct 16 — One of China’s front-running coronavirus vaccine candidates was shown to be safe and triggered immune responses in a combined early and mid-stage test in humans, researchers said.

The potential vaccine, dubbed BBIBP-CorV, is being developed by the Beijing Institute of Biological Products, a subsidiary of China National Biotec Group (CNBG).

It has already been approved for an emergency inoculation programme in China targeting essential workers and other limited groups of people facing high infection risk.

However, whether the shot can safely protect people from the Covid-19 disease that has killed more than one million people worldwide will only become clear when final Phase III trials — which are ongoing outside China — are complete.

BBIBP-CorV is one of at least 10 coronavirus vaccine projects globally to have entered Phase III trials, four of which are led by Chinese scientists, according to the World Health Organization.

It did not cause any severe side effects, while common mild or moderate adverse reactions included fever and pain in injection sites, according to a paper published yesterday in medical journal the Lancet.

The results came from a combined Phase I and Phase II trial involving more than 600 healthy adults conducted between April 29 and July 30.

Two injections of BBIBP-CorV at three different doses generated antibodies in all recipients of each group, including older participants, although the data does not prove the vaccine is efficacious, researchers at the CNBG subsidiary, Chinese disease control authorities and other research institutes said in the paper.

Antibody levels in recipients aged 60 and above were lower and took longer to increase significantly than those in younger participants, the results showed.

The study did not discuss whether the shot could elicit and maintain cell-based immune responses, another important weapon of the human immune system, which could be crucial if antibody-based immunity alone cannot stave off the virus.

Apart from BBIBP-CorV, CNBG, a unit of state-owned China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm), has another similar candidate developed by a different subsidiary which is also being tested overseas in Phase III trials and used in China’s emergency use programme.

A CNBG executive said last month the two candidates could potentially obtain conditional approval for use in the general public this year.

The other candidate by CNBG also induced antibodies without causing serious side effects in early and mid-stage trials, a research paper showed in August. — Reuters

- Joined

- Jun 27, 2018

- Messages

- 31,528

- Points

- 113

Ah tiong land has the vaccine,,,ang mor lands are fucked

US$60 experimental COVID-19 vaccine rolled out in east Chinese city

FILE PHOTO: A worker performs a quality check in the packaging facility of Chinese vaccine maker Sinovac Biotech, developing an experimental coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccine, during a government-organized media tour in Beijing, China, September 24, 2020. REUTERS/Thomas Peter

16 Oct 2020 02:48PM (Updated: 16 Oct 2020 02:50PM)

Bookmark

BEIJING: A US$60 double-dose experimental COVID-19 vaccine is being made available to some residents in an eastern Chinese city, health officials have said, the first details of a mass roll-out for an as-yet unproven vaccine.

Officials in Jiaxing city said Thursday that residents aged between 18 and 59 with "urgent needs" can seek consultations at clinics for a Sinovac Biotech vaccine that authorities have been giving to groups such as medical workers.

The statement from the centre for disease control and prevention in Jiaxing, which is located in China's northern Zhejiang province, did not specify what constituted "urgent needs".

Authorities did not say how many people in the city had been given the vaccine, which comes in two doses, administered up to 28 days apart and costing a total of 400 yuan (US$59).

READ: COVID-19 vaccine candidate from China's CNBG shows promise in human test, study shows

China has already given hundreds of thousands of essential workers at ports, hospitals and other high-risk areas across the country an experimental vaccine, according to officials.

But even as 11 Chinese vaccines have entered clinical trials - with four in advanced Phase Three trials - none have been approved for mass market distribution.

China is desperate to win the global race for a vaccine against a virus which emerged in the central city of Wuhan, as it seeks to complete its narrative of recovery from the public health and economic calamity.

READ: Chinese city of Qingdao punishes two officials over COVID-19 cluster

China has approved some candidates for emergency use, with officials saying they have not seen serious adverse reactions.

Beijing has also made bold predictions on a broader roll-out before year-end as it battles a storm of international criticism over its early handling of the outbreak.

Health officials told a press conference last month that the country expects to be able to produce 610 million vaccine doses annually by year-end, stressing it would be affordable.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has also previously declared that Chinese vaccines would be made a "global public good".

READ: China to purchase COVAX vaccines for 1% of population, says foreign ministry

China has signed up to a World Health Organization-led bid to ensure future COVID-19 vaccines are distributed to developing countries, the biggest economy yet to join the attempt to control the pandemic.

Beijing has not given details on how much money it would commit to the deal, which has a fundraising goal of US$2 billion and aims to provide 92 low and middle-income countries with a future vaccine.

US$60 experimental COVID-19 vaccine rolled out in east Chinese city

FILE PHOTO: A worker performs a quality check in the packaging facility of Chinese vaccine maker Sinovac Biotech, developing an experimental coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccine, during a government-organized media tour in Beijing, China, September 24, 2020. REUTERS/Thomas Peter

16 Oct 2020 02:48PM (Updated: 16 Oct 2020 02:50PM)

Bookmark

BEIJING: A US$60 double-dose experimental COVID-19 vaccine is being made available to some residents in an eastern Chinese city, health officials have said, the first details of a mass roll-out for an as-yet unproven vaccine.

Officials in Jiaxing city said Thursday that residents aged between 18 and 59 with "urgent needs" can seek consultations at clinics for a Sinovac Biotech vaccine that authorities have been giving to groups such as medical workers.

The statement from the centre for disease control and prevention in Jiaxing, which is located in China's northern Zhejiang province, did not specify what constituted "urgent needs".

Authorities did not say how many people in the city had been given the vaccine, which comes in two doses, administered up to 28 days apart and costing a total of 400 yuan (US$59).

READ: COVID-19 vaccine candidate from China's CNBG shows promise in human test, study shows

China has already given hundreds of thousands of essential workers at ports, hospitals and other high-risk areas across the country an experimental vaccine, according to officials.

But even as 11 Chinese vaccines have entered clinical trials - with four in advanced Phase Three trials - none have been approved for mass market distribution.

China is desperate to win the global race for a vaccine against a virus which emerged in the central city of Wuhan, as it seeks to complete its narrative of recovery from the public health and economic calamity.

READ: Chinese city of Qingdao punishes two officials over COVID-19 cluster

China has approved some candidates for emergency use, with officials saying they have not seen serious adverse reactions.

Beijing has also made bold predictions on a broader roll-out before year-end as it battles a storm of international criticism over its early handling of the outbreak.

Health officials told a press conference last month that the country expects to be able to produce 610 million vaccine doses annually by year-end, stressing it would be affordable.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has also previously declared that Chinese vaccines would be made a "global public good".

READ: China to purchase COVAX vaccines for 1% of population, says foreign ministry

China has signed up to a World Health Organization-led bid to ensure future COVID-19 vaccines are distributed to developing countries, the biggest economy yet to join the attempt to control the pandemic.

Beijing has not given details on how much money it would commit to the deal, which has a fundraising goal of US$2 billion and aims to provide 92 low and middle-income countries with a future vaccine.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 729

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 521

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 498