- Joined

- Sep 22, 2008

- Messages

- 84,314

- Points

- 113

Emasculation method

A small hut near the Forbidden City, called a ch’ang tzu, was used for the operations. A daozi jiang, or “knifer”, was responsible for the castrati throughout the process, including the healing stages.

Why beauty was a curse for women in imperial China

He charged six taels (US$84) for the operation, and worked with several apprentices. The abdomen and upper thighs of the patient were tightly bound with bandages to prevent haemorrhaging.

The local anaesthetic during the late Qing dynasty was hot chilli sauce. The parts to be removed were disinfected by washing them three times in hot pepper water.

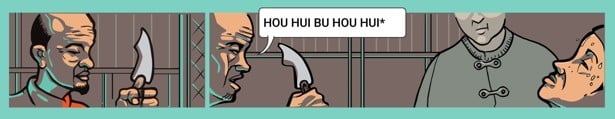

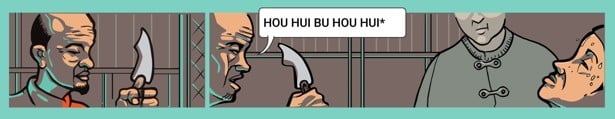

One man would separate the patient’s legs and hold him down firmly, so as to prevent any sudden movement. Two other men would hold him round the waist and pin down his arms.

The surgeon would approach with a small, slightly curved blade in his hand. Facing the prospective eunuch, he would ask: “Will you regret it or not?”

If the man showed any doubt, the operation would be halted. But if he gave his consent, the knife was put to work. Both the scrotum and the penis were removed, generally with a single slash.

A pewter needle, or spigot, was carefully inserted into the main orifice at the root of the penis to prevent urethral stricture. The wound was carefully bound with paper that had been soaked in cold water.

After dressing the wound, assistants walked the eunuch around the room for three hours before letting him lie down. The spigot prevented the eunuch from urinating.

He would also suffer from extreme thirst because he was forbidden to drink for three days after the operation.

The spigot was removed after three days. The operation was deemed a success if urine flowed out. If no urine appeared, nothing could save the eunuch from a painful death. This happened in about 2 per cent of cases.

The wounds usually healed after 100 days. The new eunuch would then go to the imperial household to assume his duties.

Bao, or treasure

Bao translates as “the three preciouses” – the testicles and penis. The new eunuch’s bao was put into a container with a capacity of about 24 fluid ounces, sealed, and then placed on a high shelf.

The “precious” was kept for two reasons:

1. Every time a eunuch received an advance in rank he had to pass a strict examination. Promotion was impossible without the bao.

The examination process was called yan bao, and was lead by the head eunuch. The inspection was often a source of profit for knifers, because sometimes careless or ignorant eunuchs forgot to claim their “precious” after emasculation. They would then be forced to pay a high price to recover the bao. Bao were sometimes borrowed, purchased or rented.

2. When a eunuch died, he was buried with his bao. If he didn't have his own, he would try to obtain another before his death.

Eunuchs wanted to be as complete as possible when leaving this world because they believed they would have their masculinity restored in the afterlife. Tradition had it that Jun Wang, the king of the underworld, would turn those without their bao into a female mule. The ancient Chinese had a great fear of deformity

A small hut near the Forbidden City, called a ch’ang tzu, was used for the operations. A daozi jiang, or “knifer”, was responsible for the castrati throughout the process, including the healing stages.

Why beauty was a curse for women in imperial China

He charged six taels (US$84) for the operation, and worked with several apprentices. The abdomen and upper thighs of the patient were tightly bound with bandages to prevent haemorrhaging.

The local anaesthetic during the late Qing dynasty was hot chilli sauce. The parts to be removed were disinfected by washing them three times in hot pepper water.

One man would separate the patient’s legs and hold him down firmly, so as to prevent any sudden movement. Two other men would hold him round the waist and pin down his arms.

The surgeon would approach with a small, slightly curved blade in his hand. Facing the prospective eunuch, he would ask: “Will you regret it or not?”

If the man showed any doubt, the operation would be halted. But if he gave his consent, the knife was put to work. Both the scrotum and the penis were removed, generally with a single slash.

A pewter needle, or spigot, was carefully inserted into the main orifice at the root of the penis to prevent urethral stricture. The wound was carefully bound with paper that had been soaked in cold water.

After dressing the wound, assistants walked the eunuch around the room for three hours before letting him lie down. The spigot prevented the eunuch from urinating.

He would also suffer from extreme thirst because he was forbidden to drink for three days after the operation.

The spigot was removed after three days. The operation was deemed a success if urine flowed out. If no urine appeared, nothing could save the eunuch from a painful death. This happened in about 2 per cent of cases.

The wounds usually healed after 100 days. The new eunuch would then go to the imperial household to assume his duties.

Bao, or treasure

Bao translates as “the three preciouses” – the testicles and penis. The new eunuch’s bao was put into a container with a capacity of about 24 fluid ounces, sealed, and then placed on a high shelf.

The “precious” was kept for two reasons:

1. Every time a eunuch received an advance in rank he had to pass a strict examination. Promotion was impossible without the bao.

The examination process was called yan bao, and was lead by the head eunuch. The inspection was often a source of profit for knifers, because sometimes careless or ignorant eunuchs forgot to claim their “precious” after emasculation. They would then be forced to pay a high price to recover the bao. Bao were sometimes borrowed, purchased or rented.

2. When a eunuch died, he was buried with his bao. If he didn't have his own, he would try to obtain another before his death.

Eunuchs wanted to be as complete as possible when leaving this world because they believed they would have their masculinity restored in the afterlife. Tradition had it that Jun Wang, the king of the underworld, would turn those without their bao into a female mule. The ancient Chinese had a great fear of deformity