- Joined

- Aug 20, 2022

- Messages

- 19,857

- Points

- 113

China bans electric vehicles from underground carparks

They explode “as if packed full of toxic dynamite” - and one nation has already started cracking down on electric vehicles as a result. Jamie Seidel

Jamie Seidel@JamieSeidel

5 min read

September 14, 2024 - 2:16PM

They flare out in a jet of flame with vicious intensity. They explode as if packed full of toxic dynamite. And when lithium-ion batteries burn, nothing can extinguish them.

This is why Chinese hotels and property managers have begun to ban all electric vehicles – scooters, e-bikes, family cars or commercial vans – from their undercroft car parks.

But are they falling for one of the human brain’s most ancient weaknesses? Or taking sensible precautions in the face of a new, unanticipated threat?

A flash in the pan

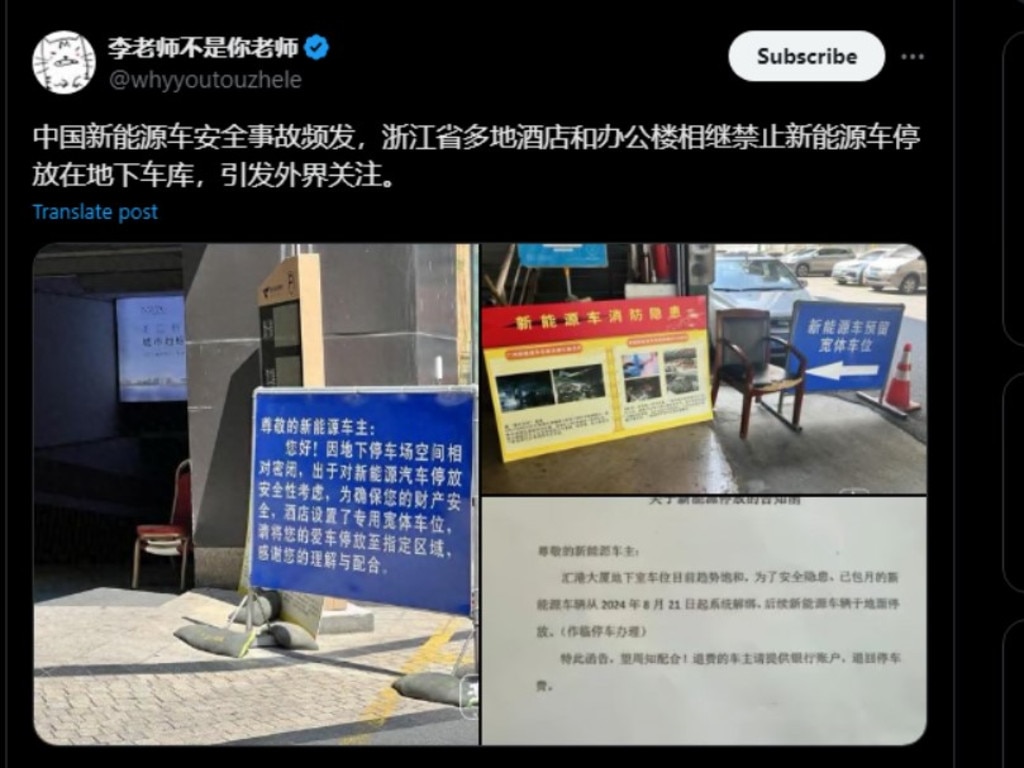

“Hotels and other buildings in Hangzhou, Ningbo, Xiaoshan and other places in Zhejiang have banned electric vehicles from entering underground garages for safety reasons, sparking heated discussions,” Chinese online dissident “Mr Li is not your teacher” reported in a post to X (which is banned in China) in September.

One of three photos attached to the post shows a sign in front of the Huigang Building in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, instructing owners of electric vehicles to divert to a nearby parking lot with “wide open spaces”.

Local news reports that property owners were spurred into action after 11 intense battery fires in Zhejiang’s capital, Hangzhou, in May of this year.

“Based on the characteristics of electric vehicle fires and our hotel’s firefighting capabilities, we think it safer not to allow them into the underground garage,” RFA quotes one five-star hotel owner as stating.

The reports have revived fears that the new low carbon emission technology may be more trouble than it’s worth.

But analysts say the problem is the novelty and newness of all-electric vehicles – and not necessarily the battery technology itself. At least, not if quality control standards are met during the manufacture of such vehicles, and if they’re handled correctly by their owners – just as mandatory safety measures must be built into petrol-powered vehicles and the process of refuelling and maintaining them.

Exploding fears

RFA quotes a Hangzhou electric car mechanic saying he’s experiencing more and more people expressing their concerns after viewing social fires involving battery-pack powered vehicles online.

One such viral social media post involved a Hangzhou car showroom catching fire after a display car spontaneously combusted.

“We’ve seen so many cases of electric vehicles going up in flames spontaneously, or causing major fires in collisions and accidents,” Xu added.

“A lot of basement parking lots are designed with low ceilings, meaning that fire trucks can’t get inside.”

But Xu obliquely hinted at a common cause.

“I know lawyers, and they tend to buy Tesla because there are fewer reports of Tesla accidents. They are safe, and they give everyone stronger information,” he said anecdotally. “But there are many spontaneous combustion of new energy vehicles in China, resulting in casualties.”

Exploding and combusting electric vehicles (EVs) are real, as are traditional petroleum-based vehicle fires.

But do social media algorithms, which train themselves to get your attention by whatever means necessary, overemphasise the threat because of its novelty?

“How likely would an electric vehicle battery self-combust and explode?” a University of California, Berkeley, assessment reads.

“The chances of that happening are actually pretty slim: Some analysts say that gasoline vehicles are nearly 30 times more likely to catch fire than electric vehicles. But recent news of EVs catching fire while parked have left many consumers – and researchers – scratching their heads over how these rare events could possibly happen.”

Thermal runaway

Petrol burns vigorously. And if an open container fills an enclosed space with fumes, the fuel-air mix is highly explosive.

The lithium-ion batteries have their own – very different – risk scenarios.

“They’re the same powerhouses that fuel our smartphones and laptops – celebrated for their ability to store heaps of energy in a small space,” argues Edith Cowan University academic Muhammad Rizwan Zhar.

“Nonetheless, when EV batteries do overheat, they’re susceptible to something called thermal runaway.”

That’s when physical damage triggers a chemical chain reaction within the battery.

It can be a short circuit. It can be a puncture. Or an external heat.

Such damage can lead to a high-temperature fire or toxic gas explosion.

“About 95 per cent of battery fires are classed as ignition fires, which produce jet-like directional flames. The other 5 per cent involve a vapour cloud explosion,” says Swinburne University Professor of Future Urban Mobility Hussein Dia.

He says most battery fires are linked to e-scooters and e-bikes.

“In the first half of 2023, EV Firesafe data show they accounted for more than 500 battery fires, 138 injuries and 36 deaths worldwide,” Professor Dia writes.

“Over the same six months, 35 electric vehicle battery fires resulted in eight injuries and four deaths.”

He says this is most likely linked to poor quality design and manufacture, but also to rough treatment and the use of inappropriate chargers by owners.

“Electric cars and trucks use the same battery technology but have more sophisticated designs,” Professor Dia adds.

“Advanced cooling systems keep their batteries at optimal temperatures during everyday driving and recharging. This makes them much safer than batteries in e-scooters and e-bikes.”

Reality bites

Two spectacular EV fires in New South Wales in September last year led to a spike in fears relating to lithium-ion batteries.

Five cars were destroyed when a damaged battery fell from a car parked at Sydney Airport.

On the same day, the tail shaft of a truck that had fallen on a road smashed a car’s battery pack near Penrose, initiating a fire.

Such lithium-ion EV fires will inevitably become more common.

It’s basic maths.

The more buyers are drawn to their green credentials and dramatically lower operating and maintenance costs, the more EVs will appear on Australian roads.

The more EVs on the road, the more accidents and incidents they’ll be involved in.

“The surge in electric vehicle numbers means funding is needed now to ensure firefighters can deal effectively with any fires that do happen,” warns Professor Dia.

For the moment, Tesla recommends that – in the event of a battery fire – it’s best to let it burn.

“Instead of snuffing out the flames, water could actually fuel the fire and cause it to intensify,” says Zhar.

“This is because the water’s reaction with the lithium can produce flammable hydrogen gas – adding more of a hazard to an already perilous situation.”

Likewise, water on a petrol fire can simply cause the fire to spread. That’s why foam and dry powder fire extinguishers were invented to smother the flames.

A similar means of smothering a lithium-ion battery fire is yet to be developed.

Tesla says in a 2020 report that their cars recorded one fire for every 330 million kilometres driven. It adds that official US government data states the rate for petrol and diesel vehicles was one for every 30.6 million kilometres.

Independent, verifiable and comprehensive data, however, is limited.

For example, the average Australian EV is just four years old. For internal combustion engine vehicles, it’s 15 years.

More Coverage

“We still have limited data on fire risk in electric vehicles, most of which are relatively new,” says Professor Dia.

“More statistically reliable comparisons require more data over much longer time frames.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel