- Joined

- Jul 18, 2014

- Messages

- 6,290

- Points

- 113

See CB kia face also dulan.Commentary: DBS CEO’s 30% variable pay cut raises issues of accountability

Singapore banks rely heavily on "pay for performance" practices to reward senior management. They must ensure that remuneration policies drive the right behaviour, says NUS corporate governance expert Mak Yuen Teen.

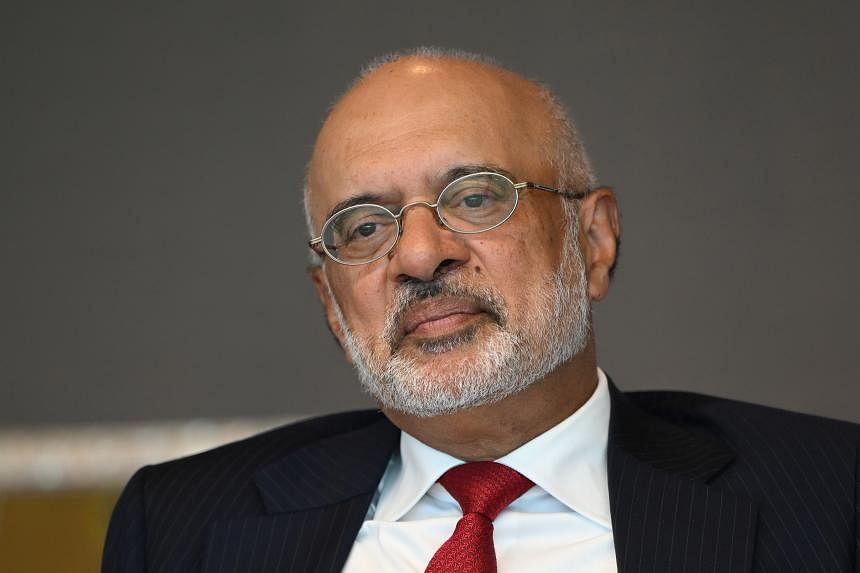

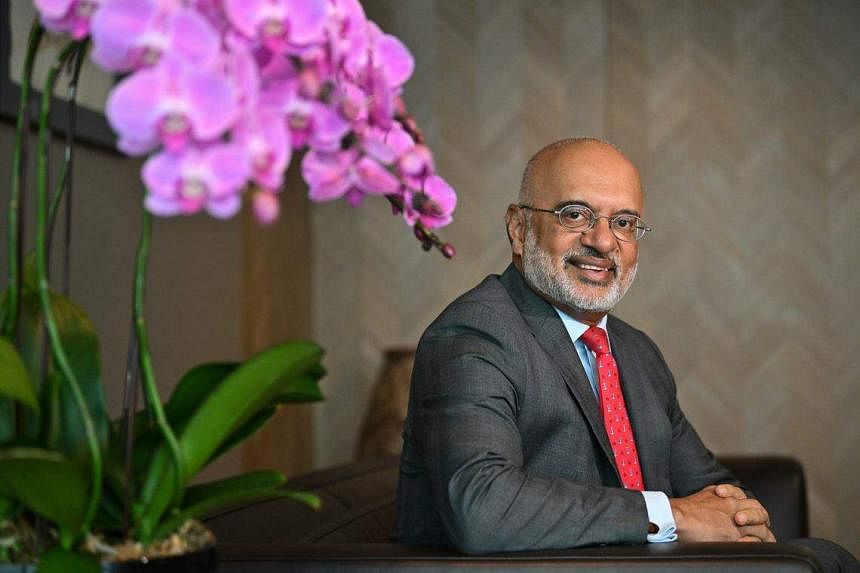

Mr Piyush Gupta, the DBS chief executive officer, had his variable pay cut by 30 per cent in 2023, as a result of the digital disruptions experienced by the bank's customers. (Photos: Reuters)

Mak Yuen Teen

14 Feb 2024

SINGAPORE: Last week’s news that DBS had cut the variable pay of its CEO Piyush Gupta by 30 per cent delivered on the board’s promise in November 2023 that senior management would be held accountable for the bank’s repeated and prolonged digital service disruptions.

Collectively, the variable pay of members of the bank’s group management committee was reduced by 21 per cent. Mr Gupta’s pay cut amounted to S$4.14 million (US$3.08 million).

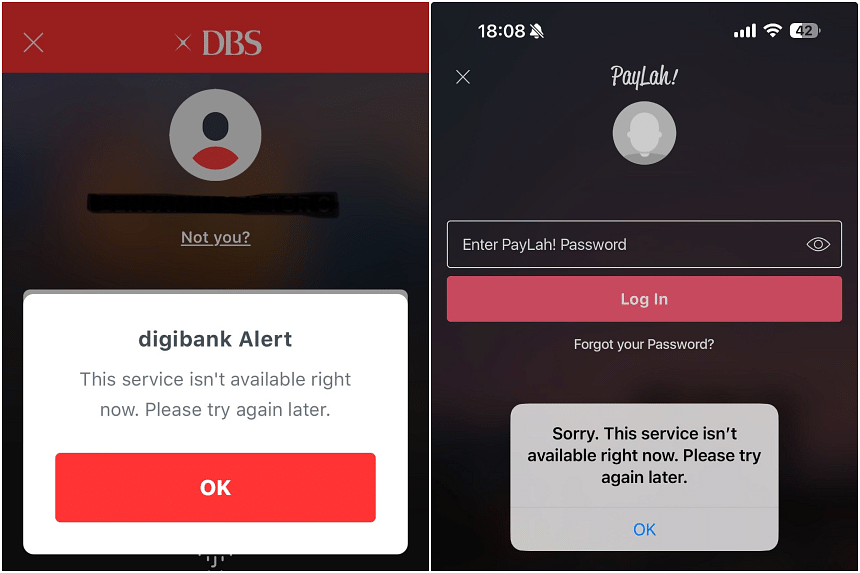

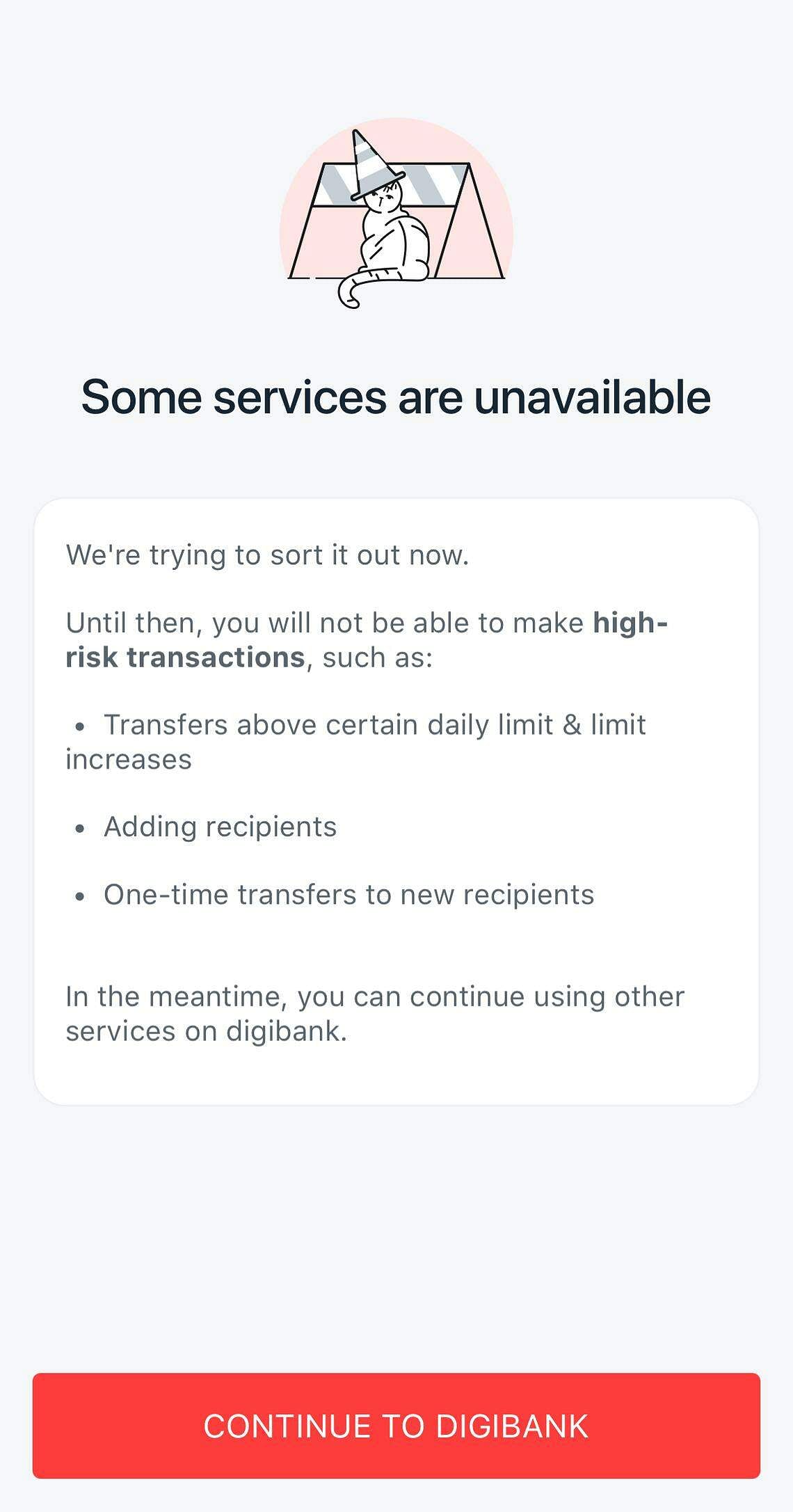

DBS online banking and payment services were disrupted several times last year, leaving many customers unable to pay their transactions and draw money from automated teller machines (ATMs). This culminated in the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) imposing restrictions on DBS’ activities to ensure that it focuses on restoring the resilience of its digital platforms.

To date, DBS has spent about S$25 million out of a special budget of S$80 million set aside in November last year to enhance system resiliency, on items such as infrastructure, hiring of consultants and reallocation of resources, said Mr Gupta in a results briefing on Feb 7.

PIYUSH GUPTA’S PAY AND PERFORMANCE

In 2022, Mr Gupta was paid S$15.4 million, including deferred remuneration and benefits, making him the highest-paid bank CEO in Asia Pacific that year. With the recently announced pay cut, Mr Gupta would get about S$11.26 million in 2023, assuming his base salary and benefits remain unchanged from 2022. DBS provides the breakdown of remuneration in its annual report in March.

Interestingly, despite DBS’ two-day digital banking service outage in November 2021, Mr Gupta’s total pay that year was nearly 50 per cent higher at S$13.6 million compared to 2020. Granted, his 2020 pay was cut, like his counterparts at other banks, as COVID-19 hit profits across the industry.

However, his 2021 package also exceeded his 2019 total pay of S$12.1 million, and his variable pay in 2021 was 55 per cent higher than in 2020. Both his annual cash bonus and deferred remuneration increased compared to the earlier years, and increased further in 2022.

The 2021 digital disruption was mentioned in several places in that year’s annual report. However, it was not mentioned in the assessment of the CEO performance. Instead, it cited Mr Gupta’s role in leading DBS to “deliver its best year ever in 2021, not only in terms of financial performance but also across a range of key scorecard goals”.

Mr Gupta’s significant pay cut this year is likely the result of the board exercising its discretion to adjust his remuneration, rather than him not meeting specific key performance indicators (KPIs).

During the bank’s results briefing last week, Mr Gupta reportedly stressed the bank’s record earnings, said that everything else was extraordinarily strong, including its customer feedback score, and referred to the disruptions as “tech instances”.

DBS uses a balanced scorecard approach to measure its success in serving stakeholders and executing its long-term strategy. The balanced scorecard has a 40 per cent weighting on “traditional key performance indicators”, 20 per cent on “transform the bank” and 40 per cent on “areas of focus”, in which qualitative priorities are disclosed within each pillar.

DBS also discloses outcomes for these priorities, through trends in some quantitative indicators but mostly through qualitative assessments. Based on the priorities and outcomes disclosed in its recent annual reports, it is unclear how outcomes which may be particularly important to DBS customers, such as service availability, data privacy and cybersecurity resilience, are prioritised and whether they will affect senior management remuneration.

COMPENSATION PACKAGES AT OTHER BANKS

The three local banks are quite aggressive in using variable pay practices – so-called “pay for performance”. Between 2018 and 2022, the variable pay percentages of all three banks' CEOs were between 80 per cent and 91 per cent of their total pay every year, except for OCBC in 2021 when it changed its CEO.

In contrast, the variable pay percentages for the CEOs of the "Big Four" Australian banks – Commonwealth Bank (CommBank), National Australia Bank (NAB), Westpac and ANZ Bank – were generally in the range of between about 40 per cent and 60 per cent over the past five years.

The Australian banks’ CEOs were also paid consistently less than their Singaporean counterparts. For example, CommBank’s CEO Matt Comyn was paid the equivalent of S$6.44 million for the latest financial year, based on the current exchange rate and on a comparable accounting basis.

CommBank’s market capitalisation is about twice DBS’, its total assets about 40 per cent higher, it trades at a price-earnings ratio of more than twice that of DBS, and its total shareholder return is also superior.

The CEOs of the other three Australian banks were paid between S$5 million and S$5.4 million in the latest financial year. NAB is also bigger than DBS, while all the Big Four Australian banks are larger than OCBC and UOB.

While one cannot simply compare pay across markets or based on bank size, it does raise the question as to whether such large differentials are justified, when we take into account differences in competitiveness and regulatory environment of the banking sector in the two countries.

More importantly, the high reliance on variable pay requires that appropriate and challenging hurdles are set for performance. Otherwise, there is a risk of remuneration driving the wrong behaviour or resulting in excessive remuneration. In addition, there needs to be transparency on how performance is measured and how specific KPIs affect senior management remuneration.

ACCOUNTABILITY OF BANK CEOS

Although the Australian banks’ CEOs have relative lower pay at risk, they are nevertheless held accountable when things go badly wrong.

Over the last five years, NAB and Westpac fired their CEOs, with no annual bonuses paid and forfeitures of deferred remuneration for certain years. To be fair, in the case of NAB, it was for serious misconduct that received particularly strong criticism from the Royal Commission into misconduct in the financial services sector in Australia, followed by revelations of serious fraud involving a senior staff due to excessive delegation by the CEO and poor internal controls. For Westpac, it violated money laundering and terrorism financing regulations more than 23 million times.

Elsewhere, there were bank CEOs who resigned over digital disruptions. In October 2023, the CEO of Canada’s Laurentian Bank resigned following a significant IT outage. Mizuho Financial Group CEO stepped down in April 2022 after it was criticised by Japan’s banking regulator for shortcomings in governance and corporate culture that were thought to be behind a series of system glitches in 2021.

MORE TRANSPARENCY NEEDED

Although banks here have not faced allegations of widespread misconduct like the Australian banks, there are nevertheless important takeaways from the findings of the Royal Commission there that may be relevant.

First, balanced scorecards that are used by banks may not be achieving their objectives. Second, there is a need to review remuneration policies at all levels and in different functions. Third, and most importantly, culture, governance and remuneration are key causes of misconduct – and they are inextricably linked.

Given the significant reliance of our local banks on variable pay to reward their senior management, they need to ensure that their remuneration policies drive the right behaviour.

For financial KPIs, there is little or no emphasis on total shareholder returns, which matters to investors. In the case of DBS, deferred remuneration does not appear to come with further performance conditions, as DBS disclosed that vesting is based on time rather than future performance. Although they are subject to malus (forfeiture) or clawback, this is unlikely to be used for events such as digital disruption.

Remuneration policies of the local banks are also lacking in sufficient transparency. KPIs are vague, their relative importance unclear and evaluation of achievement likely to be highly subjective. This makes it challenging to use remuneration to hold CEOs accountable.

While the DBS board has shown that it is prepared to exercise discretion in cutting its CEO pay, boards need to strike an appropriate balance between objectivity and discretion. There is room for banks here to improve the transparency regarding their senior management remuneration.

Ultimately, the remuneration policies for senior management and even rank-and-file employees must be subject to appropriate oversight by a truly independent committee. If the remuneration committee and the board approve a policy that drives the wrong behaviour, then they should bear some responsibility.

Mak Yuen Teen is Professor (Practice) of Accounting and director of the Centre for Investor Protection at the NUS Business School, where he specialises in corporate governance.

Should claw back all his salaries and make him a bankrupt then send him back to the shithole where he belongs.