Dubbed torture, ID policies leave transgender people sterile

-

1/15

-

2/15

Singapore Transgender An Agonizing Choice

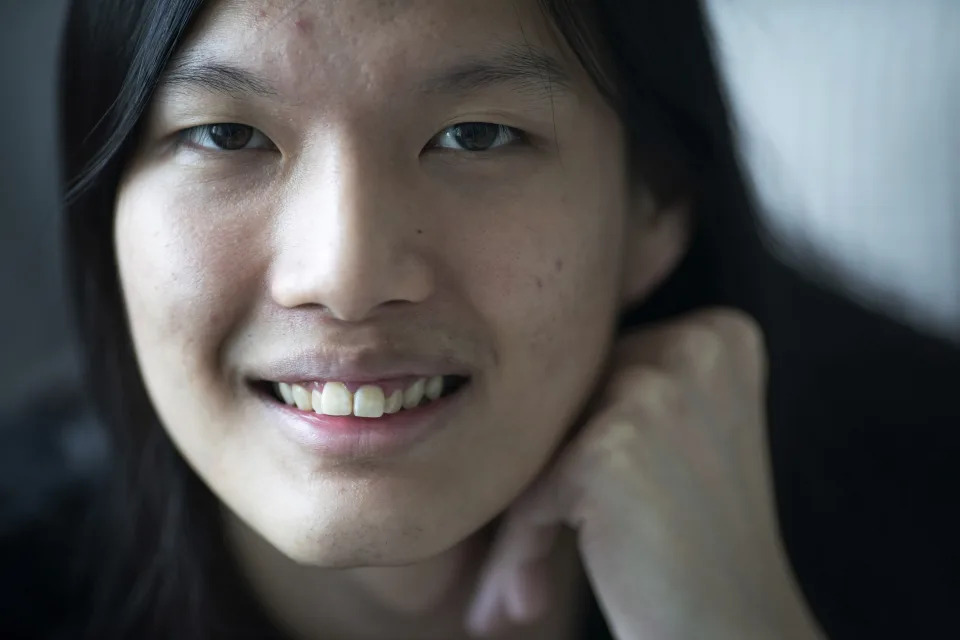

Lune Loh, 25, a transgender woman, poses for a portrait in Singapore, on Thursday, Aug. 18, 2022. She was raised as a boy by a protective mother and a conservative, stern father she grew to fear. Though he socialized Loh to be masculine, she knew early on that her body did not match who she was. Her first realization -- or "flash point" -- that something was off came one night at age 8, when she caught her distorted reflection in a window and suddenly imagined herself with long hair. (AP Photo/Wong Maye-E)

ASSOCIATED PRESS

KRISTEN GELINEAU

Fri, 11 November 2022 at 5:00 am·5-min read

SINGAPORE (AP) — She was the only woman soldier working in the guard room, surrounded by men who harassed and frightened her after she said she was transgender. She tried to ignore them as they opened up their shirts and pretended to rape each other, while beckoning her to join them.

And then one day, as Lune Loh stood under the searing Singaporean sun, one of those men took his rifle and tried to shove it between her legs.

She was a woman. She was not supposed to be here, because Singapore’s compulsory, two-year military service is required only for 18-year-old men. But under Singapore law, she was still considered a man, because she had not undergone surgery that would render her sterile.

Across the world, scores of countries still require transgender people to submit to such surgeries before their genders are legally recognized, a practice international human rights bodies have condemned as torture. These policies have left untold numbers of transgender people with an agonizing choice between their fertility and their identity.

For those who opt against surgery, the policies’ consequences can be severe, limiting their prospects for jobs, housing, marriage and safe passage through the world. Since their identification documents list their genders as the opposite of how they present in public, they can easily be outed, leading to everything from bureaucratic hassles to life-threatening confrontations.

Loh has become an unusually visible transgender rights activist in Singapore, a rigidly controlled city-state that only announced it would decriminalize sex between men in August.

At 25, she finds herself grappling with questions about her future, like whether any company will ever employ her, or whether she will ever be able to have a biological child, all because her government refuses to see her for who she is.

“People are not getting housing, people are not getting jobs … that’s basically what we’re fighting for,” she says. “We just want to help people survive another day, another month, another year.”

At the heart of the debate over gender recognition laws is the importance of identity.

The legal documents that define our identity are crucial to navigating life and the world, from getting a bank loan to crossing a border. In much of the world, changing gender markers on identification documents remains impossible.

Other countries allow such changes, but often with draconian prerequisites including sterilization, psychiatric interventions, and — for married people — mandatory divorce. In recent years, human rights groups and transgender advocates have increasingly called for the abolishment of these conditions.

“There’s a lot of requirements in most of these laws imposed on trans people which are all violating the basic human rights — the right to privacy, the right to bodily integrity, the right to non-discrimination, the right to identity,” says Julia Ehrt, executive director of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, or ILGA World.

Surgery makes some transgender people feel more comfortable in their bodies, but others consider it medically unnecessary, invasive and painful or prohibitively expensive.

Gender-confirmation surgery can involve a variety of procedures that alter a person’s sexual characteristics, some of which lead to permanent sterility.

In some countries, sterilization is in itself a prerequisite for legal gender recognition, explicitly spelled out in the law. In others, the wording is vaguer, requiring some form of surgery without specifying what procedures are mandated or whether sterility needs to be an outcome.

That is the situation in the U.S., where states that require proof of transition-related surgery do not clarify what procedures they will accept, says Olivia Hunt, policy director for the National Center for Transgender Equality. Thirteen U.S. states and territories have a surgical requirement to update gender markers on birth certificates, she says, and four have a surgical requirement for updating driver’s licenses.

In a statement to The Associated Press, Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs said the information on Singaporeans’ national identity cards reflects a person’s “sex,” which the government determines based on the person’s “biological and physical attributes.” To change that marker requires “proof of surgery, and the complete alteration of one’s physical reproductive attributes,” the ministry said.

“This allows the government to implement policies and laws based on sex in a consistent manner,” the ministry said.

Human rights watchdogs have spent years demanding an end to policies like these. But many countries have been slow to respond. In 2019, Japan’s Supreme Court upheld as constitutional the country’s gender recognition law that requires surgical sterilization.

Some governments have made changes. In 2018, Sweden became the first country to financially compensate transgender people who were sterilized under its old policy, and Germany is considering doing the same.

Cathrin Ramelow, a 58-year-old German transgender woman, is fighting for compensation and an apology from the government. In 2000, she underwent surgical sterilization, welcoming the chance to end her double life. But afterwards, she says, she agonized over what she had lost.

“You know there’s something wrong with you and you can’t have children anymore,” she says. “I cried some days.”

Years later, Loh would make the opposite choice. But she found that it, too, came with a steep cost.

Her enforced military service was so brutal she contemplated suicide. And other challenges awaited.

In 2019, Loh and her family travelled to neighboring Malaysia. The Malaysian immigration officer stared at Loh’s passport, which still lists her gender as male. “You should go cut your hair,” the officer snapped.

The words sent a chill through Loh. She knew that in Malaysia, simply being transgender is considered a crime. She had read stories about transgender people there being mobbed and killed.

She hurried across the border. Now, she makes sure to sweep her long hair back at checkpoints.

“I’m terrified of traveling now partially because of that,” she says.

Among the many fears Loh has about her future, finding a job tops the list. “Will they reject me because I’m trans?” she wonders.

Loh’s mother, Stella Wong, worries about how her daughter will navigate a future in which so many options have already been ripped away.

“But I have no choice,” Wong says. “Because in Singapore, we abide by the rules. Me too.”