https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/ins...ation-fdi-cross-border-investment-trends.html

Article

10 minute read 28 February 2023

Is deglobalization in the cards?

The February 2023 Economics Spotlight takes a closer look at the trends in cross-border investment to gauge if concerns around deglobalization hold water.

Patricia Buckley

United States

Bhavna Tejwani

India

Dating back to the global financial crisis, many economic observers have worried that a trend of deglobalization has been underway, threatening to reverse decades of gains from trade. However, similar to a recently published Deloitte study that looked at trade flows, we find no evidence of deglobalization when considering trends in cross-border investment.

Learn more

In “Globalization is here to stay,

1” Deloitte economists Ira Kalish and Michael Wolf analyze one of the major indicators of globalization: trade in goods. For the purpose of this report, we also assessed cross-border investment flows to evaluate changes, if any, in patterns of financial integration between economies. Specifically, we: i) noted the decline in global investment flows but also the increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) stock; ii) acknowledged the vulnerability of foreign investment to economic shocks and policy shifts; iii) noted the evidence on resilience of investment flows; iv) distinguished between conduit and productive investment; v) examined alternative measures of investment to overcome inadequacies in FDI data; and vi) noted future challenges for cross-border investment flows. We concluded that though cross-border investments are vulnerable to shocks in economies and policy shifts, there is evidence of resilience in the levels of foreign investment.

We take a deeper dive into each of these aspects:

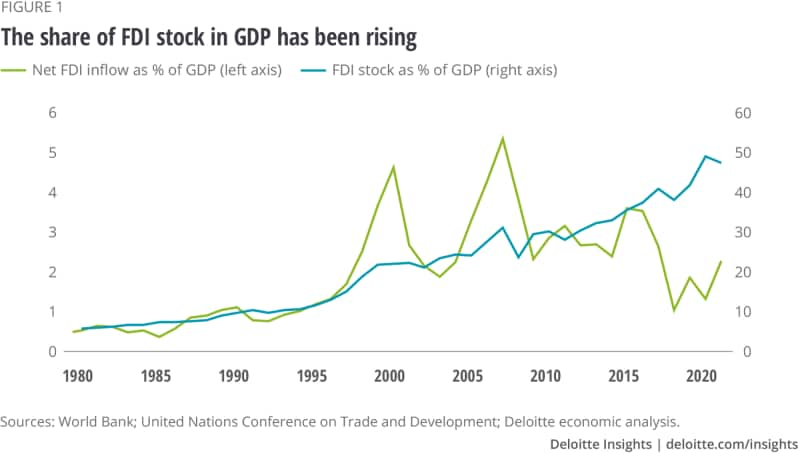

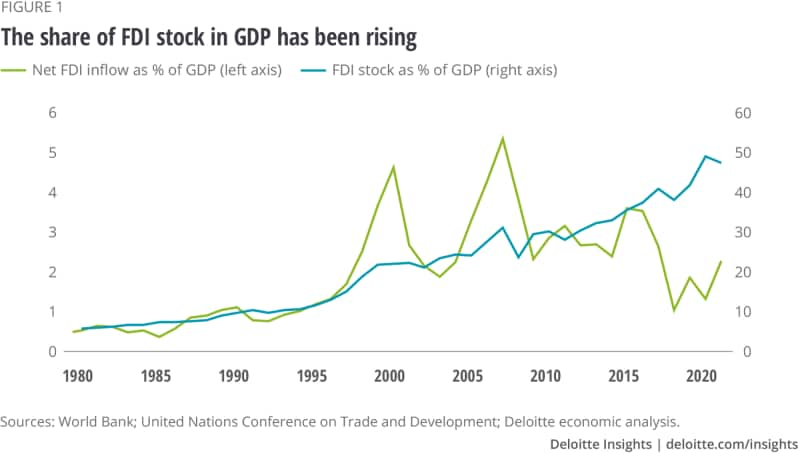

FDI flows versus stock: Post the global financial crisis, net global FDI inflows have not been growing as fast as global gross domestic product (GDP), mainly due to declining rates of return and a less favorable policy climate.

2 However, the growth in FDI flows has been sufficient enough to increase FDI stock as a percent of GDP. Barring the initial setbacks during shocks to the economy, such as during the global financial crisis and the initial emergences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of FDI stock in GDP has been rising.

Download

Share

Vulnerability of foreign investment to economic shocks and policy shifts:

Download

Share

Vulnerability of foreign investment to economic shocks and policy shifts: Foreign investment is channeled into the creation of productive assets via greenfield investments, or through the purchase of existing assets via mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The United Nations (UN) also reports data on international project finance, a mechanism to channel investment in infrastructure and other sectors relevant for sustainable development.

3 These components of FDI respond differently to uncertainties in the economy and the policy environment.

While greenfield investments appear to be more vulnerable to economic shocks, M&A and international project finance are closely linked to financial markets and are more responsive to policy initiatives and changes. In 2021, FDI flows rebounded from the low levels reached during the pandemic in 2020.

4 This recovery was driven by a rebound in M&A markets and international project finance due to a return to accommodative monetary policies and an increase in infrastructure stimulus packages across economies. However, the recovery in greenfield investments remained subdued.

Download

Share

Resilience of investment flows:

Download

Share

Resilience of investment flows: Although foreign investment is sensitive to changes in policies, there is evidence of resilience after the initial impact wears off. For instance, in 2018, the United States enacted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), which strengthened the ability of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS) to review foreign investment for national security consideration, even if it did not result in the control of a US business.

5 While not explicitly aimed at China, the number of CFIUS cases involving Chinese investors fell between 2017 and 2020 before rebounding in 2021,

6 as Chinese investors appear to have adjusted to the new rules. The data on M&A also suggests that the CFIUS turned cautious post-FIRRMA but is now stabilizing in its reviews.

The growth in inward investment in the United States declined during 2018–2020 but rebounded in 2021. In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that in 2021, the United States was the world’s top destination for FDI, while China also moved up a notch to the third position.

7

Download

Share

Download

Share

Despite a rise in protectionist sentiment and talk of nearshoring amid global supply chain pressures during the pandemic, the Peterson Institute for International Economics notes that inward FDI in China rose by a third, to reach a new all-time high, allaying concerns around deglobalization.

8 Further, the Peterson report notes that a majority of the firms in the United States and Europe with investments in China do not plan to pull out of the economy amid an increasingly favorable policy climate.