The Economy is Great. The Middle Class is Mad

Jeff Swope felt the first spurt of anger bubble up when he learned in February that his landlord was raising the rent on the empty two-bedroom apartment next door by more than 30%, to $2,075 a month.

Though Swope, a 42-year-old teacher, and his wife Amanda Greene, a nurse, make $125,000 a year, they couldn’t handle that steep a rent increase—not alongside the student loans and car payments and utility bills and all the other costs that have kept growing for a family of three. “The frustration—it was always a frog in the boiling water type of thing. I’d always felt it, but on a basic level. Something’s always brewing,” says Swope, from his modest apartment, where Atlanta Braves bobbleheads compete with books for shelf space. “We looked at the rent increase, and it was like, OK, this is ridiculous. I was like, ‘What the???’”

For Jen Dewey-Osburn, 35, who lives in a suburb of Phoenix, the rage arose when she calculated how much she owed on her student loans: although she’d borrowed $22,624 and has paid off $34,225, she still owes $43,304. (She’s in a dispute with her loan servicer, Navient, about how her repayments were calculated.) She and her husband know they’re more fortunate than most—both have good jobs—but they feel so stuck financially that they can’t envision taking on the cost of having children. “It’s just moral and physical and emotional exhaustion,” she says. “There’s no right choices; it feels like they’re all wrong.”

The exasperation of Omar Abdalla, 26, peaked after his 12th offer on a home fell through, and he realized how much more financial stability his parents, who were immigrants to the U.S., were able to achieve than he and his wife can. They both have degrees from good colleges and promising careers, but even the $90,000 down payment they saved up was not enough when the seller wanted much more than the bank was prepared to lend on the home they wanted.

Abdalla’s parents, by contrast, own two homes; his wife’s parents own four. “Their house probably made more money for them than working their job,” he says. “I don’t have an asset that I can sleep in that makes more money than my daily labor. That’s the part that kind of just breaks my mind.”

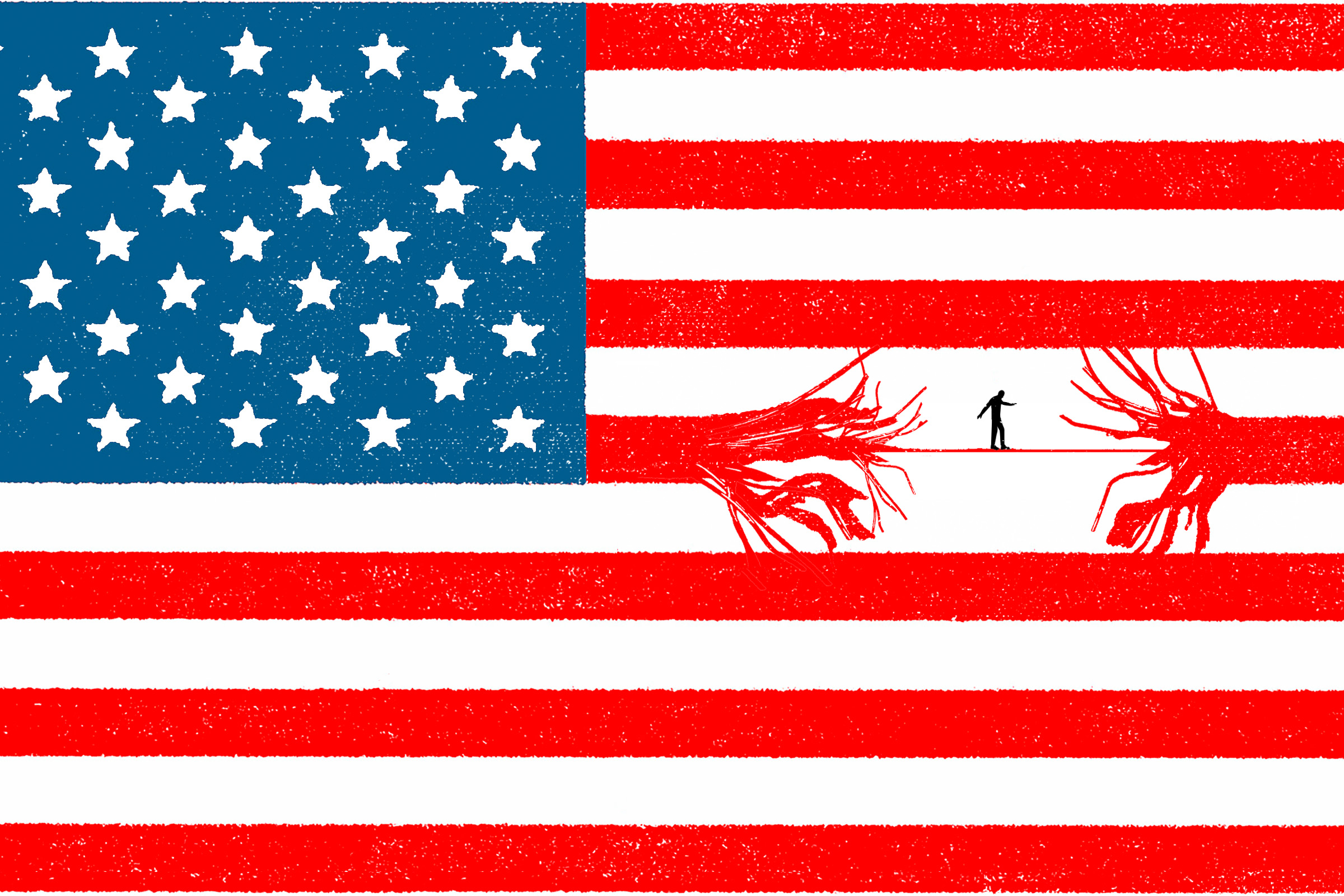

Middle-class U.S. families have been treading water for decades—weighed down by stalled income growth and rising prices—but the runaway inflation that has emerged from the pandemic is sending more than a ripple of frustration through their ranks. The pandemic seemed at first as if it might offer a chance to catch up; they kept their jobs as the service sector laid off millions, their wages started climbing at a faster rate as companies struggled to find workers, and they began saving more than they had for decades. About one-third of middle-income Americans felt that their financial situation had improved a year into the pandemic, according to Pew Research, as they quarantined at home while benefiting from stimulus checks, child tax credits, and the pause of federal student-loan payments.

But 18 months later, they increasingly suspect that any sense of financial security was an illusion. They may have more money in the bank, but being middle class in America isn’t only about how much you make; it’s about what you can buy with that money. Some people measure that by whether a family has a second refrigerator in the basement or a tree in the yard, but Richard Reeves, director of the Future of the Middle Class Initiative at the Brookings Institution, says that what really matters is whether people feel that they can comfortably afford the “three H’s”—housing, health care, and higher education.“Our income supposedly makes us upper middle class, but it sure doesn’t feel like it."

In the past year alone, home prices have leaped 20% and the cost of all goods is up 8.5%. Families are paying $3,500 more this year for the basic set of goods and services that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) follows than they did last year. Average hourly earnings, by contrast, are down 2.7% when adjusted for inflation. That squeeze has left many who identify as middle class reaching to afford the three H’s, especially housing. In March, U.S. consumer sentiment reached its lowest level since 2011, according to the University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers, and more households said they expected their finances to worsen than at any time since May 1980.