Ranting on Facebook on Sunday evening, sacked by Monday lunchtime. Such was the lot of Ms Amy Cheong, formerly assistant director of the National Trades Union Congress’s (NTUC) membership department.

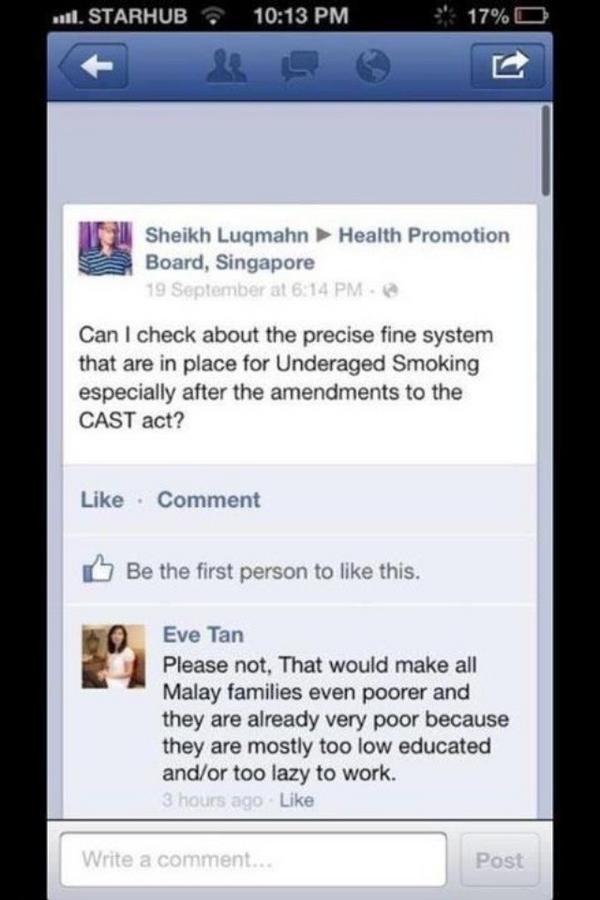

On Oct 7, she made a Facebook post complaining about Malay weddings and making derogatory remarks about Malays.

It went viral that night, attracting fire on Twitter and Facebook – as well as the attention of NTUC, who said just past midnight that it was investigating the matter. By lunchtime on Monday, it had fired Ms Cheong.

Some netizens praised NTUC’s swift reaction. But others wondered if it - together with the fierce campaign against her mounted by Netizens – was an overreaction.

One view often offered in mitigation in such incidents is that the perpetrator thought it was private or was simply young and foolish.

This type of reasoning is starting to sound increasingly hollow with every new incident.

First, most people - even children - have learnt by now that nothing on the Internet is really private unless locked down (and even then, a ‘friend’ or ‘follower’ might well expose you).

Second, it rests on the false assumption that an employee’s personal social media use is not an employer’s business.

This may be the first time a worker in Singapore has lost their job over a Facebook post – publicly, at least. But such sackings are old news on the Internet, with numerous articles and blogs on the phenomenon.

Virgin Atlantic flight attendants have been sacked for insulting passengers; radio hosts for off-the-air ranting. Racist remarks got a British pub landlord fired last year(2011) – as they did a bartender in Chicago this April.

And there are inarguable ways in which a Facebook post could be a sackable offence – if it reveals confidential information, for instance. The mere fact that the post was on Facebook does not make it off-limits for censure.

But even if Ms Cheong had reason to know that what she was doing was wrong and likely not private, was NTUC right in firing her for one racist Facebook remark?

Surely – goes the argument – NTUC could have counselled Ms Cheong instead (which it did, before firing her). Ms Cheong could have been allowed to continue in her post, hopefully wiser and more tolerant for the experience.

It is hard to say whether NTUC ‘overreacted’ in terms of being fair to Ms Cheong, or giving her a second chance. But it is easy to see why it did what it did – and in purely instrumental terms, it was no overreaction.

First, NTUC’s “zero tolerance” stance for racism is perfectly understandable in Singapore, given the sensitivity with which racial issues are treated here. Anything less than sacking Ms Cheong might be interpreted as compromising the central national value of racial harmony.

Secondly, as a labour movement built on “inclusiveness” and meant to represent all workers, NTUC has an especial responsibility to take a firm stance against bigotry. An organisation which does not condemn prejudice against minorities may alienate them with its inaction.

Thirdly, under the glare of social media’s spotlights, employers might feel an understandable pressure to come down harshly on any misdemeanour – and to be seen to be doing so. If NTUC had not fired Ms Cheong, it would likely have received flak for that.

The consequences of NTUC’s move are a separate matter. In previous episodes of online racism, some have criticised heavy-handed moves such as police reports, arguing that it is more fruitful to let racism be defeated in open debate. Ms Cheong’s sacking might also give ammunition to the anti-political correctness brigade, who think that any reaction to racism is overreaction and that minorities are just ‘being too sensitive’.

Still, if nothing else, Ms Cheong’s fate should make keyboard racists think twice before spewing their bile online. Yes, this would let such quiet bigots go scot-free, sparing them from public scrutiny – but it also spares the targets of racism from having to hear the same, old, ugly comments. And that must surely be worth something.

By Janice Heng

[email protected]

On Oct 7, she made a Facebook post complaining about Malay weddings and making derogatory remarks about Malays.

It went viral that night, attracting fire on Twitter and Facebook – as well as the attention of NTUC, who said just past midnight that it was investigating the matter. By lunchtime on Monday, it had fired Ms Cheong.

Some netizens praised NTUC’s swift reaction. But others wondered if it - together with the fierce campaign against her mounted by Netizens – was an overreaction.

One view often offered in mitigation in such incidents is that the perpetrator thought it was private or was simply young and foolish.

This type of reasoning is starting to sound increasingly hollow with every new incident.

First, most people - even children - have learnt by now that nothing on the Internet is really private unless locked down (and even then, a ‘friend’ or ‘follower’ might well expose you).

Second, it rests on the false assumption that an employee’s personal social media use is not an employer’s business.

This may be the first time a worker in Singapore has lost their job over a Facebook post – publicly, at least. But such sackings are old news on the Internet, with numerous articles and blogs on the phenomenon.

Virgin Atlantic flight attendants have been sacked for insulting passengers; radio hosts for off-the-air ranting. Racist remarks got a British pub landlord fired last year(2011) – as they did a bartender in Chicago this April.

And there are inarguable ways in which a Facebook post could be a sackable offence – if it reveals confidential information, for instance. The mere fact that the post was on Facebook does not make it off-limits for censure.

But even if Ms Cheong had reason to know that what she was doing was wrong and likely not private, was NTUC right in firing her for one racist Facebook remark?

Surely – goes the argument – NTUC could have counselled Ms Cheong instead (which it did, before firing her). Ms Cheong could have been allowed to continue in her post, hopefully wiser and more tolerant for the experience.

It is hard to say whether NTUC ‘overreacted’ in terms of being fair to Ms Cheong, or giving her a second chance. But it is easy to see why it did what it did – and in purely instrumental terms, it was no overreaction.

First, NTUC’s “zero tolerance” stance for racism is perfectly understandable in Singapore, given the sensitivity with which racial issues are treated here. Anything less than sacking Ms Cheong might be interpreted as compromising the central national value of racial harmony.

Secondly, as a labour movement built on “inclusiveness” and meant to represent all workers, NTUC has an especial responsibility to take a firm stance against bigotry. An organisation which does not condemn prejudice against minorities may alienate them with its inaction.

Thirdly, under the glare of social media’s spotlights, employers might feel an understandable pressure to come down harshly on any misdemeanour – and to be seen to be doing so. If NTUC had not fired Ms Cheong, it would likely have received flak for that.

The consequences of NTUC’s move are a separate matter. In previous episodes of online racism, some have criticised heavy-handed moves such as police reports, arguing that it is more fruitful to let racism be defeated in open debate. Ms Cheong’s sacking might also give ammunition to the anti-political correctness brigade, who think that any reaction to racism is overreaction and that minorities are just ‘being too sensitive’.

Still, if nothing else, Ms Cheong’s fate should make keyboard racists think twice before spewing their bile online. Yes, this would let such quiet bigots go scot-free, sparing them from public scrutiny – but it also spares the targets of racism from having to hear the same, old, ugly comments. And that must surely be worth something.

By Janice Heng

[email protected]