Chinese the most dishonest, Japanese and British the least, study finds

People in 15 countries took part in two tests in which they had a financial incentive to cheat; Asia’s poor showing on coin-flip test may reflect different attitudes to gambling, study’s lead author says

PUBLISHED : Tuesday, 17 November, 2015, 6:45pm

UPDATED : Tuesday, 17 November, 2015, 6:45pm

Jeanette Wang

[email protected]

Seventy per cent of Chinese tested lied about which side a coin landed on, British researchers say.

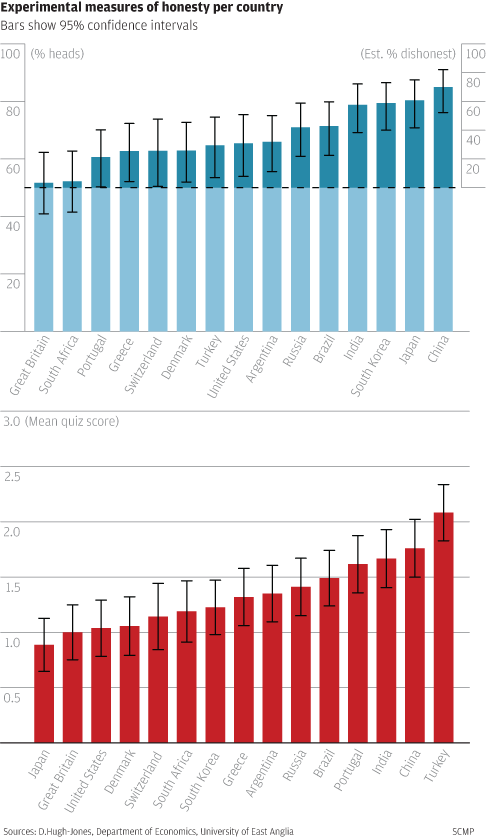

Chinese people are the most dishonest and British and Japanese people the most honest, according to a study of truthfulness involving more than 1,500 people from 15 countries.

Seventy per cent of the research participants from China cheated in one of two online tests, said researchers at the University of East Anglia in Britain. They found some dishonesty among people in all 15 countries.

In the first test, participants were asked to flip a coin and state whether it landed on “heads” or “tails”. They knew if they reported that it landed on heads, they would be rewarded with US$3 or US$5.

If the proportion reporting heads was more than 50 per cent in a given country, this indicated that people were being dishonest, the researcher said.

Participants from China were found to be the least honest, with 70 per cent estimated to have lied about which side coins landed on, compared to 3.4 per cent of British participants, who emerged as the most honest in this test.

The same participants were then asked to complete a music quiz where they were again rewarded financially if they answered all questions correctly. They were asked not to search for the answers on the internet, and had to tick a box confirming they had answered on their own before moving on to the next question.

Three of the questions were deliberately difficult so it would be highly likely that participants would need to look up the answer – meaning that getting more than one of these questions right indicated cheating.

Respondents in Japan were found to give the most honest answers to the quiz, followed by Britain, while those in Turkey were the least truthful, followed by China.

The countries studied – Brazil, China, Greece, Japan, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, the United States, Argentina, Denmark, Britain, India, Portugal, South Africa, and South Korea – were chosen to provide a mix of regions, levels of

development and levels of social trust.

Based on the results, the study’s lead author, Dr David Hugh-Jones, a senior lecturer in the university’s school of economics, noted that people’s honesty was related to the rate of economic growth of their countries, with those from

poor countries less honest than those from rich ones. However, this relationship was stronger for economic growth that took place before 1950.

Dr David Hugh-Jones of the school of economics at the University of East Anglia, which carried out the research.

“I suggest that the relationship between honesty and economic growth has been weaker over the past 60 years and there is little evidence for a link between current growth and honesty,” says Hugh-Jones, who presented his findings

last weekend at the London Experimental Workshop conference, hosted by Middlesex University, London.

“One explanation is that when institutions and technology are underdeveloped, honesty is important as a substitute for formal contract enforcement. Countries that develop cultures putting a high value on honesty are able to reap

economic gains. Later, this economic growth itself improves institutions and technology, making contracts easier to monitor and enforce, so that a culture of honesty is no longer necessary for further growth.”

In the coin flip test, the four least honest countries were China, Japan, South Korea and India. However, Asian countries were not significantly more dishonest than others in the quiz, with Japan having the lowest level of dishonesty.

Hugh-Jones says the difference between Asian and other countries in the coin flip may be explained by cultural views specific to this type of test, such as attitudes to gambling, rather than differences in honesty as such.

Participants were also asked to predict the average honesty of those from other countries by guessing how many respondents out of 100 from a particular country would report coins landing on heads in the coin flip test. Their responses

were wide of the mark.

People expected Greece to be the least honest country, but in the coin flip it was one of the most honest, while in the quiz it ranked in the middle. Of the respondents who expected less honesty in their own country, Greece and China

were the most pessimistic.

“Differences in honesty were found between countries, but this did not necessarily correspond to what people expected,” says Hugh-Jones. “Beliefs about honesty seem to be driven by psychological features, such as self-projection.

Surprisingly, people were more pessimistic about the honesty of people in their own country than of people in other countries. One explanation for this could be that people are more exposed to news stories about dishonesty taking

place in their own country than in others.”

Another finding was that less honest respondents also expected others to be less honest, as, unexpectedly, did those from more honest countries.

“People’s beliefs about the honesty of their fellow citizens and those in other countries may or may not be accurate, and these beliefs can affect how they interact,” says Hugh-Jones. “For example, a country’s willingness to support

debt bailouts may be affected by stereotypes about people in the countries needing help. So it is important to understand how these beliefs are formed.”

The study was funded by a British Academy Leverhulme Small Research Grant.