What a brain injury looks like: scientists examine blast victims

From first world war to Afghanistan, a study shines a light on a disease affecting blast victims

PUBLISHED : Saturday, 17 January, 2015, 4:16am

UPDATED : Saturday, 17 January, 2015, 4:16am

The Washington Post

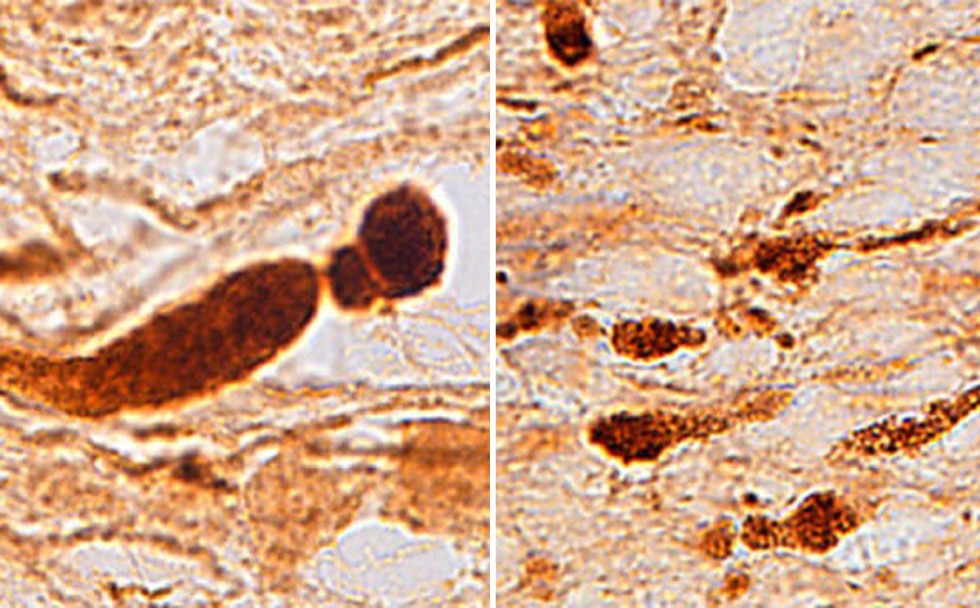

A honeycomb pattern of broken connections, primarily in the frontal lobes, are signs of a brain injury. Photos: The Washington Post

Johns Hopkins scientists have discovered what a traumatic brain injury suffered by a quarter million US combat veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan looks like and it's unlike anything they've seen before: a honeycomb pattern of broken connections, primarily in the frontal lobes, our emotional control centre and the seat of our personality.

"In some ways it's a 100-year-old problem," said lead author Vassilis Koliatsos, referring to the shell-shock victims of the first world war, tens of thousands of British soldiers who returned home physically sound but mentally wounded, haunted by their experiences and unable to fully resume their lives.

"When we started shelling each other on the Western Front of World War I it created a lot of sick people … (In a way) we've gone back to the Western Front and created veterans who come back and do poorly and we're back to the Battle of the Somme. They have mood changes, commit suicide, substance abuse … and they really do poorly and can't function. It's a huge problem."

Many of the lingering symptoms of shell-shock, or what today is known as neurotrauma, are the same as they were 100 years ago.

Only the nature of the blast has changed, from high-explosive artillery to Improvised Explosive Devices.

Koliatsos and his team examined the brains of of five recent US combat veterans, all of whom suffered a traumatic brain injury from an IED but died of unrelated causes back home.

He notes that in most Traumatic Brain Injury cases, "their attention is off, mood is off, personality is off. They're impulsive, aggressive, do poorly in school … I wanted to help my patients by trying to understand what is going on in their brains."

What he found surprised him.

"We saw a type of disease in the brain not seen before," he said. "We didn't even know if we'd see any sign of disease."

Koliatsos and his team began their research by searching for the presence of a protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is transmitted between neurons along a fibre known as an axon.

TBIs cause those axons to break and APP coalesces at those brakes, causing a swelling. In car accidents those swellings are large and bulbous, but in the veterans' brains they were medium-sized, more spheroidal and formed a honeycomb pattern near blood vessels.

The researchers also noticed these unusual swellings were particularly evident in the frontal lobes, the seat of executive functions.

Blast injuries, in large numbers, were not seen in combat veterans between the first world war and Iraq.

Vietnam, however, did produce the first diagnosed cases of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which Koliatsos believes has helped to further stigmatise current combat veterans who survive IED explosions but come back unable to resume their lives.

"We thought it was hysteria in World War I and then came PTSD in Vietnam," he said, "so we continued to think of this (hidden) injuries only as psychological."