- Joined

- Oct 3, 2016

- Messages

- 35,356

- Points

- 113

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/sin...ate-children-kids-marriage-parenthood-3354451

IN FOCUS: The ‘declining value’ of having children in Singapore – and how to fix it

"The question is, why do I need to have a kid? And if I cannot answer that, I don't think it's right to have a kid born into this world," says one Singaporean.

Singapore's total fertility rate has dropped to a record low of 1.05. CNA spoke to residents about their concerns over having children. (Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

Ang Hwee Min

@HweeMinCNA18 Mar 2023 06:00AM (Updated: 18 Mar 2023 09:28AM)

Bookmark

WhatsApp Telegram Facebook Twitter Email LinkedIn

SINGAPORE: While she was dating her future husband, Ms Michelle Lim saw having children as a logical next step.

“I thought about having children two to three years into the marriage. That was my initial plan,” the 32-year-old told CNA. Her Christian faith also put the idea of procreating and parenting in a positive light. “I thought it was very natural – until I personally started feeling a bit uncomfortable. And I started questioning, is it really that natural to have kids?”

As time passed and her career progressed, Ms Lim and her husband decided to give it another five years to have a baby – a timeline they had previously discussed in a marriage preparation course. “I think at that point I already knew … he's not super keen on children as well,” said Ms Lim, who works in the public sector.

The couple are comfortable financially and believe they can afford to have up to two kids. But they worry about the unknowns and the disruptions that their offspring could bring.

“It’s a big ‘what if’ and I think we’d rather not take the risk of having a child, even though we sacrifice the so-called infinite joy and satisfaction in child-raising,” she said.

Today, after almost 10 years of marriage, the couple remain in agreement about not having kids.

“It’s worse when you actually have one and you cannot give 100 per cent of yourself to raising that child,” said Ms Lim, citing cases of neglect or absent parents. “Both of us don’t really want that, and I see that happening if we do have a child because of the way our careers are and the kind of lifestyle we have.

"I’m going to resent it. And I don’t think it’s fair for the kid.”

Ms Lim represents a younger generation of Singaporeans questioning the need to reproduce even as older folks - and politicians - continue to urge married couples to do their “duty”.

“For what?” is the riposte offered by Candice Wang, when quizzed by friends or relatives about her firm stance against child-bearing – and before she launches into a readymade laundry list of arguments.

As a teenager in the 2000s, she envisioned marriage in her mid-twenties followed by the eventuality of one, maybe two progeny. “Back then when I wanted kids, it wasn’t so much of a ‘why’ … I was just following what people say,” said Ms Wang. ‘But I think the current climate is that people are a lot more educated, and they think for themselves.”

Now 27 years old, Ms Wang has been single for most of her life, even as she looks for a partner on dating apps. “It’s not that I don’t like kids. I like kids a lot,” she said. “It’s more like the world is not getting any better. It’s very confusing and very stressful. Why would you bring a child to this Earth just so they can suffer?”

Parents also must consider how they want to raise kids in an increasingly competitive society, Ms Wang added. “Some people say ‘just be happy can already’ but in this world, I think you can’t … You need to be a bit more ambitious to survive.”

“WE WILL NEVER GO BACK TO REPLACEMENT RATE”

A 2021 survey conducted by the National Population and Talent Division (NPTD) - housed under the Strategy Group in the Prime Minister’s Office - found that 92 per cent of married respondents wanted to have two or more children. But in practice, about half of them, or 51 per cent, had one child or none.For respondents who were single, a majority of 77 per cent indicated that they wanted children.

In a YouGov poll conducted for CNA in March, 25 per cent of 1,023 respondents aged 18 to over 55 said that - like Ms Lim and Ms Wang - they did not have children and did not want children in future.

By standard demographic indicators, the warning signs are there as well. Singapore's resident total fertility rate hit an all-time low of 1.05 in 2022, dipping below the previous record of 1.1 in 2020 and 1.12 in 2021 – and way off the replacement rate of 2.1.

The total fertility rate estimates the average number of children a woman would have over her childbearing years of 15 to 49.

Like several other developed countries, Singapore’s total fertility rate has been declining for many years, while its people are living longer. Resident life expectancy at birth has risen to more than 83 years today, up from 72 in 1980. Around one in four Singapore citizens will be aged 65 and above by 2030.

Countries like South Korea - which currently has the world’s lowest total fertility rate at 0.78 - are also coming to grips with the dire consequences of plunging birth rates and ageing populations. In Japan, an aide to Prime Minister Fumio Kishida warned that the country would “disappear” if the situation did not improve.

In a one-on-one interview with CNA, one of Singapore’s highest-ranking government officials tasked to oversee the issue said, in no uncertain terms: “We will never go back to replacement rate.”

Deputy Secretary for the Strategy Group in the Prime Minister’s Office, Ms Cindy Khoo, stressed that Singapore’s population was ageing at an alarming rate – and that the effects of a decreasing old-age support ratio would be felt sooner than most people think.

“They think that this is something that's going to be like (in) 2040, 2050,” she said. “But actually, it’s as soon as 2030, which is … just seven years away.”

By then, the ratio of working adults to seniors aged 65 and above will be 2:1, compared with 3:1 today. “Whatever you’re feeling now, come 2030, will be 33 per cent more,” said Ms Khoo.

About 40 per cent of respondents to the YouGov survey aged below 35, however, said they did not care for the consequences of Singapore having a low birth rate, while 18 per cent of respondents aged 35 and above were of the same view.

Still, with the problem escalating, the Singapore government has said that it will need to welcome immigrants to become naturalised citizens or as part of a transient workforce. “With the structure of society, it is inevitable now,” said Ms Khoo.

“We’ve kind of accepted it … The general trend (of dwindling fertility rates), I will say, is very hard to reverse.”

A MATTER OF ECONOMICS AND EMOTIONS

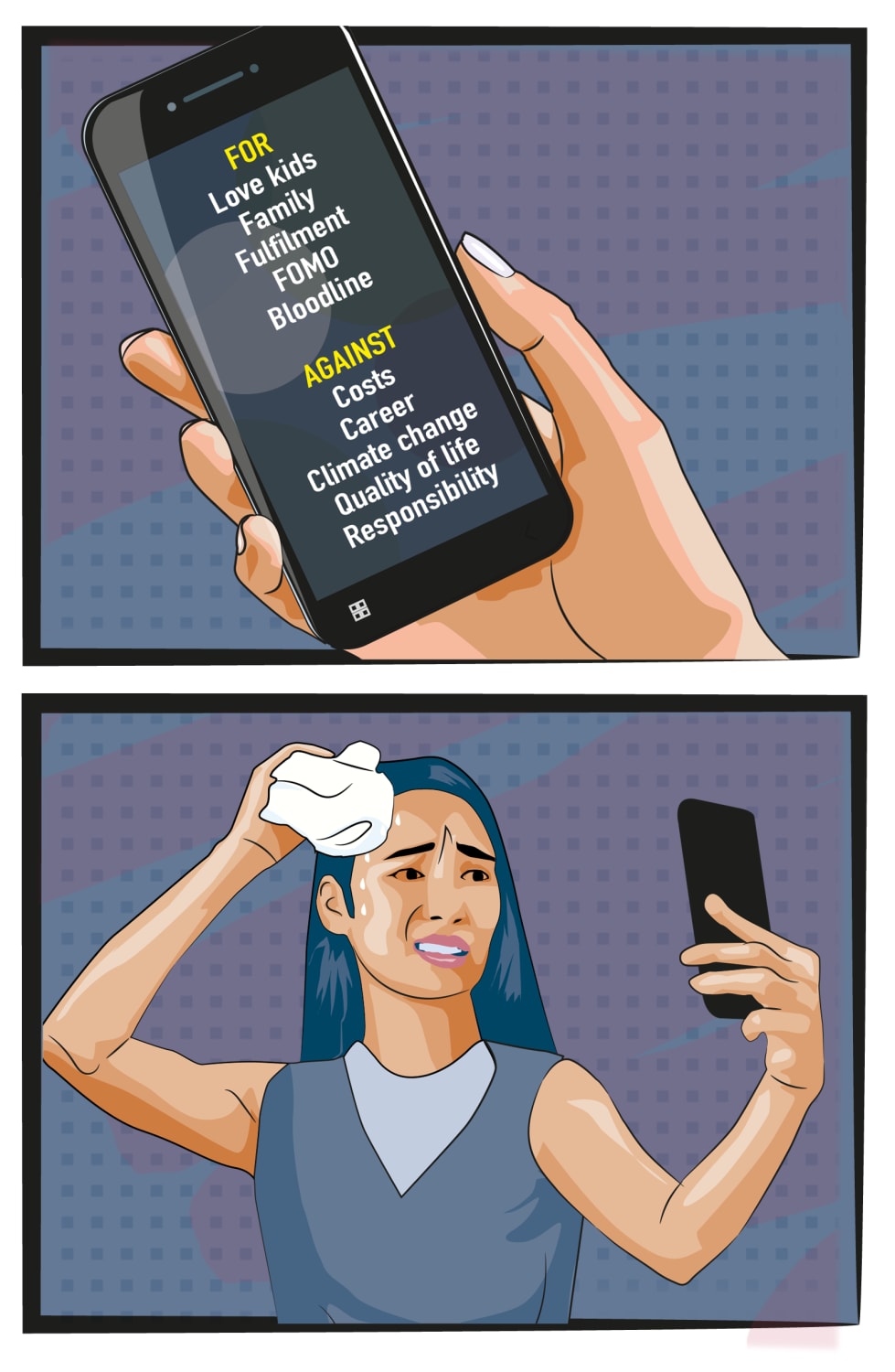

Why are Singaporeans not having more children – or not having them at all? And what would it take to make them parents? Apart from the YouGov survey, CNA spoke to 20 people - both single and married - who brought a range of views to the table.Practical factors like the cost of child-raising were cited by almost all, regardless of their opinions. This was in line with what both the YouGov and NPTD surveys found: That financial security and concerns over affordability were the most important considerations when deciding whether to have a child.

But others also highlighted reasons such as anxiety about the state of the world and Singapore society; lack of desire to parent; and reluctance to alter lifestyles for the sake of children.

Sociologist Tan Poh Lin, who studies Singapore’s birth rate, said there were three dimensions to people deciding whether to have kids: How children contribute to the well-being of a family from an economics perspective; the emotional value of having children; and the effect of parenthood on social standing.

“If you look at it from all three perspectives, there has actually been a decline in the value of (having) children,” added the assistant professor at the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

For Marsiat Jahan, building a family with kids remains on the books – but only after achieving a stable income and a place to stay. The 27-year-old is figuring out her career while her fiance currently lives in Qatar managing his own business. He hopes to move to Singapore to settle down together with her.

“The cost of living in Singapore is very high, so having children is not feasible on just a single parent’s income … if you want to provide a good future for your kids,” said Ms Jahan. “You have to start with some kind of capital.”

She still wants to eventually become a stay-at-home mother but worries her hand will be forced otherwise, due to the sheer expenses involved in raising children. “Then I would have to deal with the stress of a full-time job, the stress of being a mum, the stress of dealing with kids and everything … That would make me want to delay having kids even more.”

In these areas, Singapore has attempted to pull out the stops with a constant stream of measures and incentives to support marriage and parenthood. In last month’s Budget plan, the government increased a “Baby Bonus” cash grant by S$3,000 and adjusted the payout schedule to regular six-month intervals until the child turns six-and-a-half years old.

On the housing front, grants for families buying resale flats for the first time were raised by up to S$30,000; while young married couples were given additional ballots for their Build-to-Order (BTO) flat applications.

The Baby Bonus played its part in aesthetic therapist Thessa Young’s decision to get married while still a student – and while carrying a child conceived out of wedlock. “We had to drop out (of school), so we were quite tight (financially). We planned to get married because of the bonus to cover expenses for the time being,” she said.

Now divorced with full custody of her daughter, the 31-year-old receives alimony from her ex-husband and does her best to give the kid - currently studying in primary school - whatever she wants. “Usually I will just spend (on) her, then if I find myself feeling that my expenses are too tight, then I will just hold back on myself,” said Ms Young, adding that she has successfully applied for a BTO flat in her and her daughter’s name.

“I think now I’m a better person,” she said, adding that she used to be the carefree sort who would not come home for days on end. While the modifications to her lifestyle were difficult at first, she was so busy as a young mother that she didn’t realise she had changed her ways for her daughter.

“She did ask me before, why did I have her,” Ms Young said with a chuckle. “I didn’t know how to reply.”

Related:

'Every cent helps': More parental support welcome, but couples say it won't push them to have more children

Commentary: Parenthood incentives – Singapore cannot keep doing more of the same without knowing whether these really work

CHILDREN: “NOT REALLY VERY GOOD INVESTMENTS”?

The increasing cost of raising children - including accoutrements such as a S$1.4 billion tuition industry - comes in tandem with what Asst Prof Tan referred to as a changing “generational contract”.Today, children are not really expected to work and contribute to household expenses, so “it’s no longer a system where (they) necessarily repay their parents because they’re grateful for their upbringing”, she said. Instead of depending on their children to provide for them, people now look to the healthcare system and their own savings.

“That means that if I'm a very rational person and I only value children from a comfort perspective, actually children nowadays are not really very good investments,” the sociologist added. “In fact, they’re a net drain.”

Camille Tan, 28, and her partner Jeryl, who only wanted to be known by his first name, disagreed with this perception of children. “If you want children, you shouldn't see them as an investment for retirement,” she said, describing such thoughts as selfish.

The couple have dated for close to two years and do not intend to have children if they get married – a choice which left Ms Tan’s parents “quite upset” and Jeryl’s “a bit bummed”.

In YouGov’s survey, younger Singaporeans appeared to feel more pressure to have children from their peers, family and social groups. Among respondents aged below 35, 33 per cent agreed with this statement, compared with 18 per cent of those aged 35 and older.

“I think a lot of parents are very worried, (thinking) ‘What if you don’t have children and in future how are you going to take care of yourself?’,” said Ms Tan. “But that is something that I cannot agree on … It's your job to be financially ready to take care of yourself in the future. So, I think it's a very unfair mindset.”

Should they come to regret their decision, the couple remains open to adoption. But there are others like 39-year-old Jasmine Gunaratnam who said she has “never enjoyed the company of children”.

While she supports parenthood and pro-natalist policies from a societal standpoint, the senior director, who works in insurance, was so set in her convictions that she started thinking about how to provide for her own retirement when she was just 13 years old.

Going through school, she questioned why she felt this way, and wondered if there was something wrong with her. “Why am I not like the others, how come I don't think about marriage? Or why don’t I care about things like having a family or playing with little baby dolls, or all these expected maternal feelings?” said Ms Gunaratnam, who has been with her husband for 18 years.

Though she has since faced many questions on whether she might rue not having children in the future, her candid answers often stop her inquisitors in their tracks. “It (becomes) quite clear to them – if you don't enjoy children, then it's not good for a child where a parent doesn't enjoy their company.”

Alex Law, 38, who has been married for five years, concurred. “If you don't truly love kids, I don't think there’s a need for you to bring another life to this world. I think there's a lot more purpose to being a human or a person on Earth,” he said.

The project manager in an interior design firm travels often with his wife, doing “pretty much everything” his friends can’t do, he joked. For his peers who are parents, vacations are limited to school holiday periods; Mr Law claimed that many of them who had babies right after marriage regretted not waiting a few more years.

“Me and my wife, we both are people that know exactly what we want in life. We have a bucket list to complete, and kids are just not part of the plan. At least not for now,” he said.

“People will say I am selfish, and I agree. I am selfish, I want my life for myself.

“I’ve got nothing against kids … I know I can be a good father if I have one. But the question is, why do I need to have a kid? And if I cannot answer that, I don't think it's right to have a kid born into this world.”

The YouGov poll found that just 14 per cent of respondents aged below 35 believed that couples who can have children but choose not to were selfish. A higher proportion - 23 per cent - of older respondents aged 35 and above agreed with the statement.

“MOTHERS HAVE LOST MORAL SUPPORT”

Since she was young, dance teacher Dinie, who asked to be identified by just her first name, has told her parents that she would never want children of her own. “They were always like ‘Oh, you'll understand when you're older’. But I got older (and) that hasn't changed,” said the 25-year-old. “I have a multitude of reasons why I don't want kids and as I got older, those reasons just piled on.”Dinie, who is bipolar, said that for factors related to both her temperament and the cost of child-raising, she would not be able to give her kids the best of what life has to offer. “You won’t really know what you’re going to be like as a parent, until you become a parent,” she added. “It’s very much trial and error, and I’m not willing to put a child through that.”

Others CNA spoke to also started out dead set against having children – but changed their minds later.

Not too long ago, 28-year-old jagua artist Ng See Min thought she was not “anywhere near ready” to have a kid – and for that matter, still saw herself as one. Therapy helped her realise that she did want to start a family, but only after she and her fiance, a videographer, were more financially stable.

She has made peace with the possibility of not being able to afford luxuries like tuition or ballet classes for her children. “Last time, I was a lot more affected (by) this thought that having a child is really so expensive, if I do want to give the child the best. But then I realised all those things are external.

"The best thing I can give my child is unconditional love and time and care,” said Ms Ng. “My family grew up with nothing much. My mum … She tried her best, as much as she could, but I didn’t have a lot of things my friends had. But I feel like my childhood was not compromised in any way and I still grew up great.”

Diane Tan, 33, also recalled not being particularly enticed, in earlier years, by notions of marriage or parenting. “It meant that I needed to give up freedoms; (kids) are expensive; the idea that the woman in the household will be holding most of the caregiving arrangements. That would also mean that I might possibly have to give up my career,” she told CNA, as her one-year-old daughter crawled towards her waving a clothes hanger.

Her husband, on the other hand, always wanted children. Attending counselling together helped shape her thoughts and eventually change her mind. “What are our mutual values? What type of marriage do we want to build? That in itself gave me confidence to be like, okay, maybe I can consider having a child with this person,” said Ms Tan, who works in communications.

She said a big contributing factor to her initial uncertainty was whether she would be “a good mum”. The mindset that women have some sort of natural motherly instinct is not helpful and needs to change, said Ms Tan.

NUS’ Asst Prof Tan highlighted that other perceptions around motherhood have changed – namely in terms of status. Being a mother used to be something that was highly regarded but “more and more, mothers have lost moral support, especially if they don’t have a job”.

“It doesn’t fit in with the standard metrics of success that we now all recognise,” she said, adding that people now consider their occupation and income level when measuring social standing.

“Being a mother is not an occupation that people think of at all as work. In fact, you even have to clarify that unpaid work is actually work."

Asst Prof Tan added that where people once felt judged if they did not have children, this was increasingly no longer the case, due to greater access to other forms of gratification or sources of enjoyment in life. “Nowadays, children face a lot of competition in terms of being a source of emotional wellbeing,” she said.

“What used to give people a lot of satisfaction back then was being a mother. Nowadays, instead of being a mother, you can get other sources of fulfilment, including from your career.”

Related:

Commentary: More paternity leave is promising, but Singapore could be so much bolder

Bigger baby bonus, more paternity leave: 7 takeaways for parents from Budget 2023

“ARE WE JUST CREATING WORKERS?”

One key factor raised by those CNA spoke to was the ability to juggle their careers with finding the time and energy to take care of children.Lawyer Fattah Lattif moved overseas to the United Kingdom partly because he wanted to raise kids in an environment he considers more family-friendly. The 27-year-old, who is in a relationship but not yet married, said that while the cost of living was generally the same, a house and car were “much more attainable” – and that he enjoyed better work-life balance than in Singapore.

“If I needed to leave work at 4pm and pick my kids up, nobody would bat an eyelid. They’d just say, ‘all right, see you tomorrow’. It's never really an issue … because there is no alternative,” he said. But in Singapore, where having migrant domestic help is commonplace, employers often expect parents to choose work over their children, said Mr Fattah, adding that live-in domestic helpers were extremely rare in the UK.

Among younger respondents (aged below 35) to the YouGov survey, 35 per cent were open to having children if they could raise them overseas, compared to 19 per cent for those aged 35 and older.

Take Mr YC Chua, 33, who was against having children just two years ago. His move to the United States with his Vietnamese wife has since shifted the needle. Like Mr Fattah, he sees colleagues leaving at 3pm or 4pm to pick their kids from school – in contrast to the Singaporean workers who typically stay until 7pm or 8pm, said Mr Chua, who works in the tech industry.

“Singapore is really a stressful city, it’s so dense, it’s so crowded, we don’t really have personal space,” he added. “And your working life is so stressed, so packed, you hardly have time for yourself. And then you want to have kids?”

Where most people in the US see work as part of life, in Singapore, “working is our life”, Mr Chua claimed. “It's not very healthy for our psyche … If working is our life, then when having kids, are we just creating workers?”

All this, before even considering gender inequality in and outside the workplace – which Ms Corinna Lim, executive director of the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) rights group, pointed to as a significant factor in Singapore’s low fertility rate.

She painted a picture of more women entering the workplace and more girls graduating from universities over the past decades, with men not moving into the domestic sphere at the same rate. “This asymmetry makes child-rearing less attractive for women in Singapore, who are faced with empirical evidence that having kids is detrimental to their productivity, financial independence and retirement adequacy,” said Ms Lim.

Traditional gender norms that view women as caregivers and fathers as breadwinners create an incompatibility between work and childcare, she added. When women reach their 30s and start having children, the so-called “motherhood penalty” kicks in – where they are demoted, forced to take lower-paying, more flexible jobs, or end up leaving the workforce entirely.

The Manpower Ministry’s 2022 Labour Force Survey found that among women outside the labour force, 75 per cent in their 30s and 40s cited housework or caring for family members as reasons for not working. Childcare was the most common reason cited by those in their 30s.

Ms Lim further highlighted that workplaces in Singapore were not yet designed to facilitate women having children, or to adequately compensate them if they did. “Women have been asked during job interviews about whether they plan to have children, with breastfeeding accommodations in the office remaining uncommon,” she added, noting that there was still a 12-week difference between the allotted period for maternity and paternity leave.

Related:

Commentary: Singapore women have more equal opportunities, but some way to go for equitable outcomes

Commentary: Singapore is trying to make things better for families, but employers and employees too need to walk the talk

BALANCING THE “COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS”

The question, then, is whether there are bright spots for Singapore to cling to, in the face of an increasingly Sisyphean task of arresting a birth rate in free fall.Turning to the analogy of a cost-benefit analysis, Ms Khoo from the Prime Minister’s Office said: “I can understand if (people) feel that the choice is skewed towards not having children because it feels like the opportunity cost is too much and they cannot balance it.

“But if I increasingly make it easier for people to manage their career or make peace with whatever sacrifices they may need to make - make it not so painful, not so sharp - then maybe that balance will tilt a little bit, to make them feel ‘Okay, I need to make some adjustments, but it’s still worthwhile because of the joys of parenthood’.”

That younger Singaporeans look to the state for support in their parenting efforts seems clear, with almost half - 46 per cent - of respondents aged below 35 in the YouGov survey believing that the Singapore government was not doing enough to encourage childbearing.

But government doesn’t hold all the answers. Ms Khoo gave the example of how additional parental leave entitlements can be made into law but people may still choose not to utilise them. “I think this really requires a much broader societal coming-together, (shifting) our expectations, recognising that this is something worthwhile,” she said. “And that we should support one another in doing it, rather than make everything sort of overly legislative or hardwired.”

She said Singapore was still “in a good place” because the general societal norm remained that of a “pro-family” value system.

What about Singaporeans who don't want children at all? The government will track this “not very big” group over time, and “try to stem” shifts in this proportion, said Ms Khoo, while noting that any such change would be natural for developed countries.

But she emphasised that it would not be right to try to change the beliefs and attitudes held by this group. “At the end of it, it's still a very personal choice. They have, for whatever reason, decided that this is not for them, and I don't think we're in a position to say we want to challenge that mindset … So long as they are not saying this should be a way for society,” she added.

“What they’re asking for is ‘freedom for me to live my life my way’, and I think Singapore has space for that.”