- Joined

- Mar 11, 2013

- Messages

- 14,512

- Points

- 113

No other word in the modern world produces so much noise, yet so little meaning, as Islam.

The Arab weeps at the mosque for the “fall” of Islam—though he would not recognize it if it stood before him. The Westerner panics over the “rise” of Islam—though what rises is not a religion, but a people broken by the absence of one.

Islam today is not feared because it is strong, nor mourned because it is sacred. It is feared because it is present without form, and mourned because it is named without substance. The Islamist raises his fist in its name, while knowing nothing of its faith. The post-Christian European recoils from its sound, while having long abandoned his own.

It has become the sacred placeholder of a faithless world without meaning.

Islam today is a source of anxiety not because it is believed, but because it is no longer believable. Not by its own followers, and certainly not by its critics. What both East and West confront is the specter of a religion that speaks its name, but has no memory of its soul. The Arab imagines Islam as a lost golden age. The Western liberal imagines it as a pre-modern fossil that refuses to die. Both are wrong. What we call “Islam” today is neither threat nor salvation. It is a ruin still giving off heat—a haunted name attached to broken minds, inherited traumas, and dead concepts performing themselves by rote.

The Arab doesn’t want Islam. He wants its glory without its grammar—its pride without its prayer, its honor without its humility. The West doesn’t fear Islam. It fears the reminder that for others, belief is still possible, while for itself, it refuses to commit to anything but disbelief.

Yet honesty demands more than metaphysical diagnosis. It demands an acknowledgment of fact. The Western fears are not mere hallucinations of guilt and lost faith. They are responses to real violence, real radicalism, and real civilizational decay made flesh. There are mosques that preach death. There are many communities that seethe with resentment, that see themselves not as citizens but as avengers. There are men for whom the memory of Islam is not a mirror for introspection, but a weapon for conquest. To speak only of metaphysical confusion without speaking of these realities would be as dishonest as those who imagine that terrorism is a statistical illusion, or that cultural disintegration is an Islamophobic myth. What the West fears is not Islam itself—but the fragments of Islamism: the broken, the weaponized, the post-theological rage that wraps itself in sacred language while carrying out profane acts. It is not Islam that marches through the streets of Europe with knives and slogans. It is the wreckage of Islam, sharpened into a blade.

And it is this wreckage—psychological, political, spiritual—that we must now name, dissect, and understand without euphemism, without apology, and without hope for easy reconciliation.

What Went Wrong Revisited

Political radicalism in Muslim societies is not an eruption of atavism, nor the natural expression of Islam. It is the downstream effect of a civilizational breakdown—one in which Islam, as a normative order, was first hollowed out, then politicized, then reassembled as an ideological instrument in the vacuum left by failed attempts at Western mimicry.

Modern Arab radicalism is not a return to tradition. It is the reaction of post-traditional societies to the collapse of meaning. The late Ottoman and colonial periods severed the transmission of classical Islamic knowledge and governance. What followed was not reform but rupture. The Arab world entered the modern age not through intellectual evolution but through political humiliation—military defeat, colonial subjugation, and the dismantling of its moral and institutional universe.

The postcolonial Arab state was not a continuation of an Islamic political civilization but its negation. It emerged as a centralized, militarized apparatus modeled on European nation-states, cut off from the historical Islam, allergic to pluralism, and hostile to the remnants of religious authority it could not control. Arab nationalism, Baathism, and other secular ideologies did not fail to modernize—they succeeded in disfiguring their societies beyond recognition. They stripped Islam of its juridical and spiritual complexity and left behind only the shell of an identity, ripe for ideological reconstitution.

It is from this debris that Islamism emerged—not as a recovery of Islamic tradition, but as a post-Islamic phenomenon: a revolutionary theology manufactured in prisons, universities, and the pages of totalizing manifestos. It replaced law with rage, spiritual hierarchy with populist resentment, and jurisprudence with political will. It does not descend from al-Ash‘ari or al-Ghazali, but from Rousseau and Lenin, filtered through an inferiority complex and dressed in scriptural costume.

To ask whether Islam causes radicalism is to misread the order of causality.

Radicalism in the Arab world is not caused by Islam; it is the consequence of Islam’s evacuation—its displacement by the nation-state, its suppression by the military regime, and its reanimation in the form of ideology by those who inherited its ruins but none of its grammar.

In this sense, political Islam is not premodern but hypermodern. It is Islam abstracted, weaponized, and made legible to the postcolonial mind. It emerges not from the continuity of Islamic civilization, but from its mutilation.

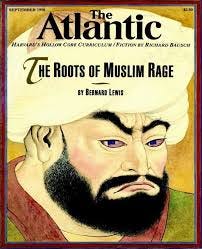

Political radicalism in the Arab world is not only a sociopolitical phenomenon—it is a psychic formation. It is the product of a soul that has been displaced from its traditional moral cosmos and reconstituted around a singular obsession: vengeance disguised as virtue.The psychology of post-Islamic radicalism is structured by resentment—not as a passing emotion, but as a metaphysical orientation. It is born from the simultaneous recognition of civilizational decline and the refusal to accept it. (This is the famous thesis of Bernard Lewis.) The radical is not simply angry; he is humiliated. And that humiliation is not processed as tragedy, but as betrayal—by history, by the West, by internal decadence, and above all, by the silent God who no longer seems to answer.

In classical Islam, dignity (karāma) was grounded in submission to divine law. But that law has been politically neutralized and culturally forgotten. In its absence, dignity must now be asserted through power. Not the power of intellectual excellence or moral exemplarity—but the brute power of retaliation. The jihadist does not want to purify society; he wants to punish it. His religion is not a source of transcendent humility, but of absolute self-righteousness. His God does not judge him; his God affirms him.

This inversion is critical: the classical Muslim feared God; the radical invokes Him to sanctify his fury.

Radical Islamism, therefore, is not too Islamic—it is insufficiently so. It lacks the memory, the intellectual patience, and the theological restraint of the tradition it claims to represent. It is the Islam of the orphaned soul, the uprooted ego, the trauma seeking metaphysical resolution through historical bloodletting. Its moral vocabulary is binary: purity and filth, submission and treason, martyrdom and apostasy. There is no room for confusion, ambiguity, or introspection—only the raw certitude of the aggrieved.

And central to this aggrievement is the Jew.

Not because of theological continuity, but because, in the footsteps of the German genius, the Jew becomes the perfect symbolic container for Arab self-contempt projected outward. The Jew, especially the sovereign Israeli Jew, embodies everything the radical cannot reconcile: historical continuity, technological competence, democratic survival, theological confidence. The Jew is not hated as a person, but as a mirror. A mirror that reflects the Arab world’s fall, and thus must be shattered.

This is why antisemitism in Arab radicalism is not a fringe impulse—it is the very theological grammar by which the radical makes sense of his defeat. The destruction of Israel is not just a political goal; it is a sacrament of self-repair.

But of course, it repairs nothing.

The radical’s rage is bottomless, because its true object—the restoration of a meaningful world—cannot be accomplished through destruction. And so the cycle deepens: humiliation, rage, sanctification of rage, violence, more humiliation. A psychic ouroboros fed by borrowed texts and amputated metaphysics.

Until the sources of moral form are reencountered, not mimicked; until the theological grammar of Islam is retrieved, not replaced; until shame is metabolized into reform, not redirected into revenge—this cycle will continue, devouring what remains of Arab and Muslim civilization from within.

We must now turn the blade inward—not only toward the object of critique, but toward the conceptual language by which that object is made visible. For the very structure we have described—the psyche of the radical as one marked by humiliation, alienation, and theological silence—is not unique to the Arab world, nor to Islam. It is, in fact, the inherited psychological architecture of modern European revolutionary thought.The idea that one lives in the shadow of a lost civilizational grandeur; that history has conspired against human dignity; that suffering is not to be endured but rectified through transformative violence—this is not an Islamic consciousness. It is a post-Enlightenment secular theodicy, born of Europe’s own metaphysical crisis.

The Enlightenment promised a rational and liberated order in place of sacred hierarchy. When this failed to materialize—when reason led to Reign of Terror, to the guillotine, to technocratic annihilation—the West produced a new myth: that redemption could be found not in God, but in revolution. Rousseau, Marx, Nietzsche—each in his way recoded the Biblical fall into a political mythos. The world is broken not because of sin, but because of power. It must be remade, not through repentance, but through revolt. Evil is no longer metaphysical; it is structural. And it must be destroyed.

It is this modern revolutionary grammar, not classical Islam, that structures the psychic language of contemporary Arab radicalism. What we call “humiliation” is, in this light, a narrative frame inherited from a secularized theology of history. The radical’s belief that his civilization has been betrayed—by Western imperialism, by secular elites, by colonial fragmentation—is not merely an emotion. It is a doctrinal conviction: that there was once unity, purity, moral coherence—and that its loss must be avenged.

This idea—that history owes us satisfaction—is a thoroughly modern fantasy. It is alien to traditional Islamic thought, which recognizes the cyclical nature of history, the inevitability of trial (fitna), and the centrality of divine sovereignty over temporal affairs. The early Muslim response to catastrophe was not revolution but renewal (tajdīd), not rupture but return (rujūʿ). The proper human response to civilizational decline was repentance, introspection, reordering—not ideological insurrection.

That this posture has been replaced by slogans of vengeance—by demands for purity through violence, by accusations of treason against metaphysical traitors—reflects the infiltration of modern revolutionary subjectivity into the postcolonial Muslim imagination. The Islamist is not a throwback to the medieval jurist; he is the mirror of the Jacobin, the Bolshevik, the committed post-Sartrean militant—mobilized by the same myth: that suffering is a cosmic injustice, and that utopia is possible if only enough blood is spilled.

Thus, the radical’s humiliation is not merely personal or cultural. It is scripted. It is the symptom of having absorbed a European eschatology of despair without the metaphysical grounding that once restrained it. The result is a psyche that rages against history as if it were a conscious betrayer, and seeks redemption not through transcendence, but through annihilation.

In this light, the Arab radical is not an expression of authentic Islam. He is the heir to a disenchanted Europe, speaking in Qur'anic idioms but dreaming in revolutionary French.

The Hidden Architecture: Civilization as a Secular Theological Concept

The modern Arab imagination has internalized “civilization” (ḥaḍāra) as both a self-description and a moral aspiration. Yet few pause to ask what this word signifies, whence it originates, and what invisible assumptions it smuggles into the very heart of Muslim self-understanding.The concept of “civilization” is a European modern construct, not an ancient or universal term. It emerges in the 18th century, particularly in French and Scottish Enlightenment thought, as a way of narrating the progressive epochal development of humanity from barbarism toward rational, moral, and political refinement. Montesquieu, Ferguson, Condorcet, and others did not merely observe differences between peoples; they constructed a hierarchy of being—one that implicitly justified imperialism, tutelage, and conquest.

Civilization, in this sense, was not descriptive. It was normative. It was the standard by which societies were judged to be legitimate or obsolete, superior or inferior, mature or primitive. Christianity had posited salvation as the telos of history. Enlightenment thought secularized this telos: salvation became civilization. To be civilized was no longer to be redeemed; it was to have conformed to an immanent, historical criterion of progress.

This shift had enormous consequences. History itself became a theological arena, but now without transcendence. It was not God who would judge the nations, but Hegel’s History—the silent tribunal, in German mold, punishing those who failed to evolve. “Progress” became the new eschaton. “Civilization” became the new Eden.

When European empires encountered the Muslim world, they found peoples whose self-understanding was not structured by this category. Classical Islamic thought had no analogue to "civilization" in the Enlightenment sense. Muslims distinguished between belief (īmān) and unbelief (kufr), between dar al-Islam and dar al-harb, between just rule and tyranny—but never between “civilized” and “uncivilized” as ontological categories of human worth. The Qur’an speaks of nations (umam) judged by their faithfulness to divine command, not their technological or political sophistication.

The Islamic view of history was moral, not developmental. Victory was not proof of virtue, nor defeat proof of backwardness. God raises and lowers nations according to wisdom hidden from human view. Thus, dignity (karāma) was anchored in submission to the divine will (islām), not in historical achievement.

It is only after military defeat, colonial subjugation, and epistemic disorientation that Arab intellectuals began to adopt the language of “civilization.” Figures like Rifa‘a al-Tahtawi, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, and later Muhammad Abduh internalized the European gaze. They sought not to reject it, but to prove that Islam could meet its standards. Thus began the long and catastrophic shift: Islam was no longer the supreme and sufficient framework of human flourishing; it was repositioned as an ingredient within “civilization”—a civilization now implicitly defined by European metrics of science, governance, and historical success, a pathological philosophy of History.

In this transformation, the concept of dīn—a total way of life submitted to God—was quietly replaced by ḥaḍāra—a historical project measured by human progress. Islam ceased to be the criterion of judgment and became itself a judged object.

Thus, the modern Arab Muslim finds himself trapped within a double alienation: he yearns for the dignity of “civilization,” but he seeks it through categories and criteria that already declare him insufficient. His rage at civilizational decline is the rage of a man who has accepted the judgment of an alien tribunal but resents the sentence.

This psychic structure is not Islamic. It is post-Christian and post-Enlightenment.

It is the secularized revenge of history masquerading as moral self-critique.

The tragedy is profound: by accepting “civilization” as the measure, Arab intellectual life guaranteed that it would forever pursue a receding horizon—chasing a redemption whose terms were set by those who first declared it deficient.

Until this architecture is dismantled—until the borrowed metaphysics of “civilization” is cast aside—no true renewal is possible. Only mimicry, resentment, and ideological revolt without end.