- Joined

- Apr 14, 2011

- Messages

- 20,647

- Points

- 113

Future-proofing malls with havens, hangouts and hubs

Global trends point to a reimagining of malls as community hubs where people go for meaningful connections, not just to shop

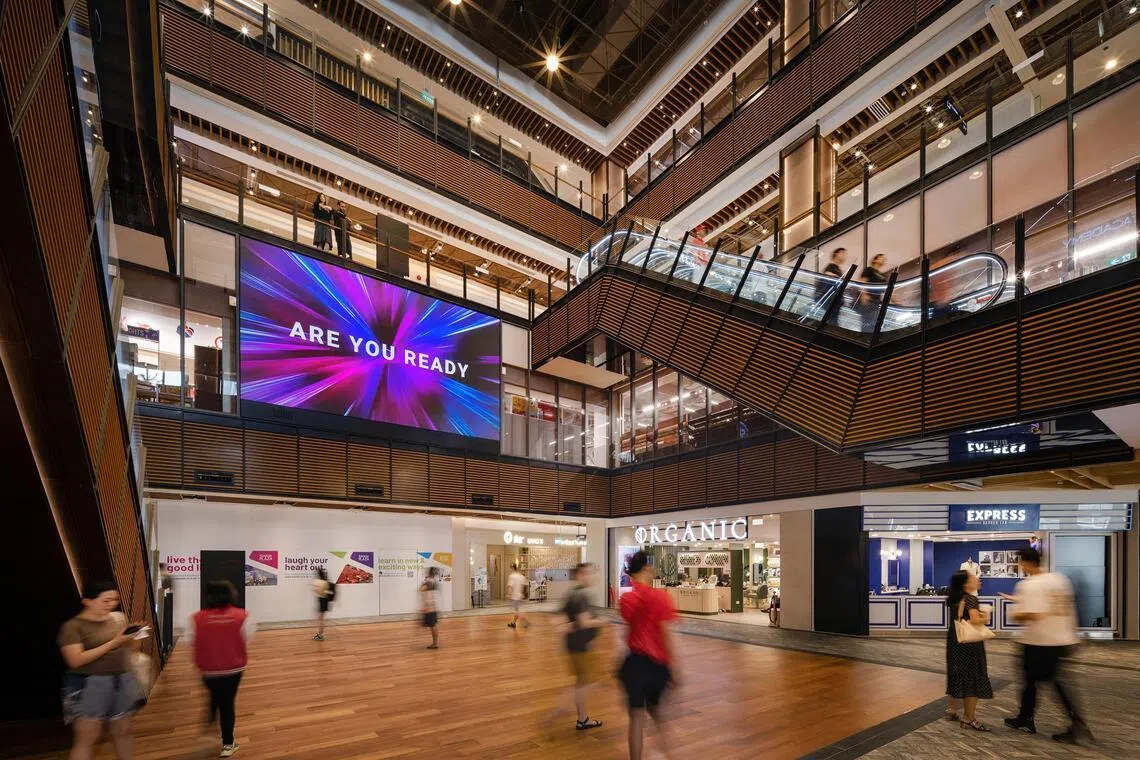

SINGAPORE – Shopping malls around the world are quietly reinventing themselves.

They are moving away from an unsustainable model of high rents and high yields per square foot to becoming “community living rooms”, where people go for urban experiences and connections in havens, hangouts and hubs instead of just browsing merchandise.

These are corners of a mall where people of all age groups linger, talk and return to, such as a pop-up community kitchen sharing recipes by home chefs or a maker space that draws both teenagers and seniors.

Data from a 2024 report by global professional services group PwC says that by 2030, 60 per cent of shoppers will expect shopping to be more personalised and centred on experiences in a multisensory physical store, instead of being focused on merchandise they can easily buy online.

Shopify echoes this lifestyle shift in its 2024 retail report. The global e-commerce platform flags experiential retail and brands using pop-ups in bricks-and-mortar stores to delight customers as mainstream strategies.

It says businesses are recognising the value of in-store shopping experiences and are crafting new ways to boost customer loyalty and generate foot traffic in competitive environments, instead of relying solely on traditional retail.

Urban anchors of a community

These “third places” anchor residents to a neighbourhood, holding the promise of deeper engagement with the community at large, says Dr Samer Elhajjar, a senior lecturer in marketing at NUS Business School.Top stories

Swipe. Select. Stay informed.

Singapore

MOE makes headway in rethinking teachers’ duties, continues efforts to ease workload: Desmond Lee

AsiaChina says it cannot accept countries acting as ‘world judge’ after US captures Maduro

SingaporeVape sellers targeting the young with devices that can play music, games

AsiaMan who allegedly filled S’pore-registered car with RON95 at Johor petrol station identified

SingaporeSingaporean of the Year finalist: Doctor gives those with intellectual disabilities dignity through healthcare

LifeRail travel, hotel rewards and more: 5 trends to shape your next vacation

OpinionAustralia’s double bonanza from rare earths

BusinessSGX rebrands equities business to SGX Stock Exchange as STI marks 60th anniversary

In urban design, the third place is a vital social setting outside of home (first place) and work (second place) where people gather informally, build community and foster a vibrant civic life. It is often public spaces such as cafes, libraries and plazas.“If landlords partnered seriously with social service agencies, malls could shift from being ‘traffic machines’ to a vital part of Singapore’s social infrastructure. And all this social energy can be observed and tracked,” Dr Samer tells The Straits Times. His broader expertise encompasses digital marketing, consumer behaviour and strategic marketing.

He says that shoppers’ time spent in shared spaces, the frequency of repeat visits, and the diversity of users across age and income will produce outcomes daily.

“A flexible studio used for intergenerational workshops or maker programmes generates vital data, while an empty show unit produces none. The data is there if landlords choose to look beyond sales conversion,” he says.

This approach reframes community programmes as strategic investments. When residents use a space regularly, they build routines around it, encounter the same people and feel safe taking children or elderly parents there.

Dr Samer adds: “For instance, a pop-up in the mall’s atrium could showcase the work of social service agencies such as the Goodlife Makan community kitchen, where shoppers can take time out from browsing goods to see how seniors living alone away from their homes reintegrate into society.”

Goodlife Makan in Marine Parade provides a sense of community for elderly residents living alone.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Goodlife Makan, run by Montfort Care, is Singapore’s first community kitchen for seniors, located at the void deck of a block of Housing Board flats in Marine Parade.

One initiative that has turned the entire shopping mall concept on its head is New Bahru in Kim Yam Road. In 2024, home-grown hospitality brand The Lo & Behold Group launched the mall as a curated campus of home-grown creativity.

Housed in the restored former Nan Chiau High School, it is a retail cluster that shines the spotlight on more than 40 Singapore brands across food, retail, wellness, education and the arts.

Apart from glitzy downtown shopping centres such as Ngee Ann City and Ion, Dr Samer argues that Singapore’s neighbourhood mallsalso have an edge.

They are woven into the housing fabric rather than standing apart from it, and are perfectly placed to act as civic stages where people talk, create, learn and access services seamlessly.

One example is Limbang Shopping Centre in Choa Chu Kang, a neighbourhood mall that relaunched in 2024 after a two-year revamp by the Housing Board.

A 2024 photo of the interior of Limbang Shopping Centre.

PHOTO: ST FILE

It reopened with more amenities, dining options and improved accessibility for residents.

Among the mall’s biggest draws is the Indian Barber Shop, which gives free haircuts to seniors aged 70 and older, as well as people with disabilities.

The Indian Barber Shop at Limbang Shopping Centre has been giving free haircuts to seniors and people with disabilities.

PHOTO: ST FILE

The indoor playground at Limbang Shopping Centre features murals of village scenes.

PHOTO: HDB

And more neighbourhood malls are being retrofitted. These include Dawson Place in Queenstown, Fajar Shopping Centre in Bukit Panjang and Joo Chiat Complex near Geylang Serai.

Over at One Holland Village – a low-rise, pet-friendly neighbourhood mall in Holland Village Way – a 1,000 sq m community hub called A Good Place was launched in February 2025.

Run by social agency Presbyterian Community Social Services, and which cost $2 million to build, the community hub supports youth with special needs and seniors through affordable enrichment and ongoing learning beyond school.

It also serves as a research site for novel calming therapies, such as a 15 deg C “cold room” with sound-based interventions, developed in partnership with local and overseas universities. Such moves position the mall as a neighbourhood support node, rather than a purely commercial space.

A Good Place is a community hub at One Holland Village.

ST PHOTO: SHINTARO TAY

Dr Samer points out that over time, a mall becomes part of the neighbourhood rhythm rather than an occasional destination. This reduces tenant risk, stabilises demand and increases long-term relevance.

“Social energy becomes a leading indicator of commercial health and resilience, not something separate. More importantly, this is not philanthropy. It is long-term asset thinking.

“When residents use a space regularly, they build habits around it and develop a sense of ownership. The mall becomes part of their daily routine rather than a transactional pit stop,” he says.

Malls as design incubators

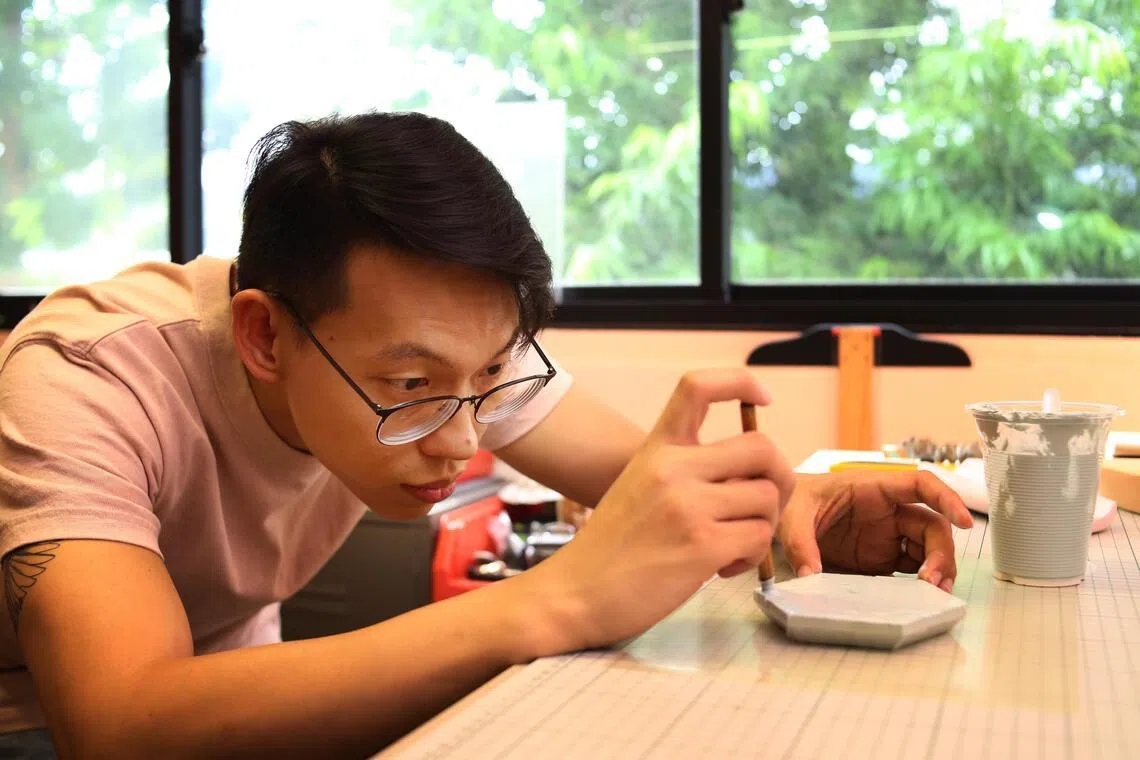

Dr Samer says another important development that local malls can be a part of is talent incubation. To do this, mall owners need to relook available space where designers who lack visibility can show their creations in selected units.Also called “urban commons”, this refers to a few high-visibility units in a mall that are deliberately treated as shared, common spaces.

The landlord curates and partly underwrites these spaces as long-term community and culture infrastructure, measuring success in participation, diversity of users and repeat visits, rather than monetisation through rental income.

Dr Samer says these spaces can also be used as maker studios where established and young designers bring their ideas to life in real time through short residencies. It allows the public to appreciate the design process, not just the end-product.

The return is not just financial. It is also reputational, social and cumulative, and dovetails with Singapore’s global status since 2015 as a Unesco Creative City of Design.

The Unesco Creative Cities Network was created in 2004 to promote co-operation with and among cities that see creativity as a strategic driver of sustainable urban development. There are now about 40 Creative Cities of Design worldwide, including Bandung, Buenos Aires, Cape Town and Shanghai.

“This model builds design literacy in the community. While shoppers learn why something costs more and what skill sets are behind it, designers gain feedback, confidence and real-world exposure. Local malls also gain identity and cultural depth that cannot be copied by foreign brands,” Dr Samer adds.

“What makes it work is not retail, branding or sales. It is purpose and continuity.”

Redefining success

Over at the Singapore office of Gensler, managing director Angela Spathonis says footfall has long been the default way to judge the success of retail and commercial spaces.She notes that footfall is easy to measure, and aligns neatly with traditional leasing and asset models.

But in heartland malls and neighbourhood centres, high numbers often reflect convenience rather than connection, with people simply passing through to run errands, pick up food or commute. Recent research conducted during Gensler’s City in 60 exhibition in Singapore suggests something different is driving meaningful use.

People linger in spaces that feel clean, green, comfortable and welcoming, with seating, shelter, and the option to eat and stay without pressure. Social interaction tends to cluster at comfortable edges and transition spaces, with food consistently acting as a social anchor.

These findings indicate that social energy depends less on spectacle than on everyday conditions that help people feel at ease.

As traditional civic spaces come under pressure, malls and neighbourhood centres have become some of the most accessible shared environments in daily life.

Shaw Plaza in Balestier Road shows how a neighbourhood mall can be repositioned as everyday social infrastructure.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Ms Spathonis says collaboration between landlords, social service agencies and designers can bring lived, ground-level knowledge into these spaces – but only if all parties are prepared to broaden their notion of success.

The firm’s recently released annual design trends report, the Gensler Design Forecast 2026, points to a wider shift away from purely transactional environments towards experience-led, relationship-driven places, especially in cities with ageing populations and rising social isolation.

In this context, value is increasingly created through emotional connection, relevance to daily life and a sense of belonging, beyond just movement and spend.

By combining retail with lifestyle- and community-oriented uses, Shaw Plaza supports routine visits and informal encounters rather than one-off transactions.

PHOTO: GENSLER

One of Gensler’s recent projects, Shaw Plaza in Balestier Road, shows how a neighbourhood mall can be repositioned as everyday social infrastructure. By combining retail with lifestyle and community-oriented uses, it supports routine visits and informal encounters rather than one-off transactions.

It now houses child-focused enrichment and care centres such as Little Splashes Aquatics, a swimming school that runs indoor heated pools and teaches babies to adults to swimmers with special needs in a controlled, warm-water environment.

These amenities are designed to draw children and parents into the mall on a routine, weekly basis, not just for shopping.

It also features family-friendly public spaces such as a landscaped sky terrace with an outdoor playground, and an 11-screen cinema with a “Dreamers” hall tailored for young children, turning the complex into a regular social outing spot for neighbourhood families.

Shaw Plaza in Balestier Road features family-friendly public spaces and an 11-screen cinema.

PHOTO: GENSLER

“While the development remains commercially viable, its relevance increasingly lies in how it encourages people to return and interact, outcomes that footfall alone cannot fully capture,” says Ms Spathonis.

On malls as incubators for smaller brands and independent design talent, she stresses that the issue is not displacing global labels, but expanding what retail space is allowed to do.

Many independent makers work in small batches, sell primarily online and lack access to visible, affordable physical space, so their work stays largely unseen in everyday settings.

Supporting them requires a departure from standard leasing logic, as independent design does not sit comfortably within fixed rents, long tenures or purely sales-driven metrics. Without structural flexibility, such initiatives risk becoming one-off pop-ups rather than sustained platforms.

But there are real-world models that are showing how this can be done.

Gensler’s Silver Room Design Lab in Chicago, the US, operates as a hybrid retail, exhibition and community space.

PHOTO: GENSLER

In Chicago, the US, the Silver Room Design Lab – designed by Gensler – operates as a hybrid of retail, exhibition and community space. It gives independent creatives a physical presence while also hosting events, workshops and cultural programmes.

The space functions less like a conventional shop and more like a platform, building visibility, dialogue and cultural relevance alongside commerce.

The Silver Room Design Lab in Chicago gives independent creatives a physical presence while also hosting events, workshops and cultural programmes.

PHOTO: GENSLER

“The deeper question is whether we are prepared to see design as part of everyday life, rather than something confined to festivals, galleries or niche audiences,” Ms Spathonis adds.

“If that mindset shifts, malls can play a meaningful role, not as full-scale incubators, but as part of a broader ecosystem that gives independent designers space to be seen and to connect with the public.”

Experiential jumping-off points

Urbanist, strategist and author Sarah Ichioka says shopping malls are a core feature of life in Singapore, so they deserve careful stewardship to ensure they serve the best interests of the majority of users.“I see many exciting opportunities for more forward-looking landlords and business improvement districts to up their game by working with partners such as social enterprises, trade associations, institutes of higher learning, and others to bring beauty, fresh thinking, meaningful employment and rewarding community interactions to selected mall units,” says Ichioka, speaking to ST from London.

She founded Desire Lines in Singapore in 2017, a cross-disciplinary studio that helps places, communities and organisations chart paths towards thriving futures. In 2021, she co-authored Flourish: Design Paradigms For Our Planetary Emergency with British architect Michael Pawlyn, which encourages readers to exercise their own agency in building regenerative places and cultures.

She says more has to be done to improve the mall experience to provide rewarding jobs, improve the lives of visitors and enhance the ambience for neighbouring businesses.

Some standout ideas for upping the ante include retail concepts such as clothes-swopping boutique The Fashion Pulpit’s Circular Fashion Hub in Jalan Besar. The store brings together 10 sustainable and equitable fashion brands, together with a host of other community services such as book swops and dance workshops.

The Fashion Pulpit’s founder Raye Padit. The second-hand store’s Circular Fashion Hub in Jalan Besar brings together 10 sustainable brands, together with other community services such as book swops and dance workshops.

PHOTO: BT FILE

Another way could be to use mall spaces as jumping-off points for immersive and place-specific cultural experiences such as social enterprise The Black Sampan’s tours, community events and heritage programmes centred on the Orang Laut, says Ms Ichioka.

The Orang Laut are indigenous sea nomads of the Malay Archipelago, known since the 14th century for their deep connection to the sea. They live mainly in boats and are renowned for their expertise as mariners, fishermen and traders.

“Mall spaces can also include credible and consistent on-site programming, such as advice for existing small business owners, workshops in specialist skills for would-be entrepreneurs, and care-and-repair sessions for customers to complement rather than compete with the growing number of pop-up markets and standalone kiosks,” she adds.

Conceptual revamp ‘long overdue’

Singaporean designer Melvin Ong prefers selling his creations online to maintaining a physical store.Renting a space can be prohibitively expensive, with monthly rentals hovering around $38,000 for a 2,600 sq ft shop space in the central District 10 area.

Mr Ong is one of many local designers who rely on teaching and sharing skills through workshops for a steadier income, rather than on revenue from the sale of his creations.

The 41-year-old founder of design studio Desinere studied furniture and interior design at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in 2005 before pursuing his degree studies in 2008 at Central Saint Martin’s School of Art and Design in London.

Mr Melvin Ong, founder of local design studio Desinere.

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

In 2012, he opened online studio Desinere, and works mainly on corporate commissions such as installations for fashion and furniture events. He also sells a curated line of designs on his webstore as well as on online art and design platform Vermillion.

He says a change in the way malls are currently managed – with an overemphasis on dollar value per sq ft – is long overdue.

There are other soft powers malls possess that are often overlooked because they cannot be quantified, he says, but which serve as community anchors that draw footfall.

“If you sit in a heartland mall long enough, a pattern emerges. People are rarely rushing. They wait. They rest. They linger between errands or after school. Some come with no clear intention to buy anything at all. These moments do not look efficient, but they are deeply habitual,” Mr Ong notes.

“Yet, heartland malls are still assessed using the same benchmarks as downtown malls, by footfall, yield and turnover. Those numbers tell us how busy a place is, but not how rooted it makes residents feel.

“They miss the quieter signs of value, how often people return, how long they stay, and whether the space feels welcoming across ages and needs.”

Thambi Magazine Store’s third-generation owner, Mr Periathambi Senthilmurugan, took over the stall from his father. He shut the store in 2024.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Mr Ong cites the closure of newsstand Thambi Magazine Store in Holland Village which brought this tension into focus.

The store’s third-generation owner, Mr Periathambi Senthilmurugan, who took over the ground-floor stall from his father, shuttered it in May 2024 due to space restrictions on his display of magazines.

“Even if it made sound commercial sense, the disappearance of Thambi Magazine Store altered the vibe and feel of the area. When familiar urban anchors vanish, something harder to replace goes with them,” Mr Ong recounts.

Artist Ronnie Tan and Mr Periathambi Senthilmurugan, owner of the former Thambi Magazine Store, in front of a mural at Holland Village MRT Station that depicts the famous newsstand.

PHOTO: ST FILE

He would like to see heartland malls reflect the spirit of their neighbourhoods in the way they curate experiences, instead of competing with the glitz and glamour of downtown shopping centres.

By including more maker spaces, residencies for designers to showcase their creations and a celebration of all things made in Singapore, heartland malls can chart their own course.

Mr Ong adds: “The works of independent designers and craftspeople offer an alternative. Their value lies not in scale, but in their presence. You see the work, the process, sometimes even the person behind it. The challenge is that most of them cannot survive long under conventional retail terms.”