- Joined

- Mar 31, 2020

- Messages

- 9,153

- Points

- 113

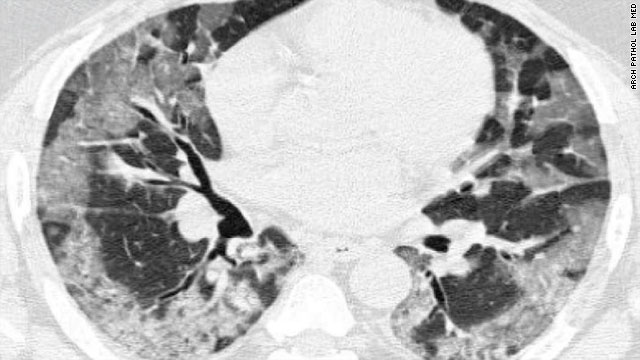

Horrifying Images Show How the Coronavirus Ravages Our Lungs

![[IMG] [IMG]](https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/c_scale,f_auto,fl_progressive,pg_1,q_80,w_1600/hnub90oz0rwps87etlol.png)

An image of SARS-COV-2 virions infecting the cells that line the airways of our lungs. The image is taken at 1 micrometer magnification.

Image: Camille Ehre/The New England Journal of Medicine ©2020

Horrifying Images Show How the Coronavirus Ravages Our Lungs

Here’s a closer look at the coronavirus that causes covid-19, courtesy of new research published in the New England Journal of Medicine Thursday. These images depicting the coronavirus en masse infecting human lung cells aren’t just for show either—they might just provide a hint as to why covid-19 can be so devastating to our bodies.

Camille Ehre, a pediatric pulmonologist and lung researcher at the University of North Carolina, and her team created the photo opportunity to understand exactly how the coronavirus interacts with the lung’s airways upon infection, as well as how these infected cells behaved once they were hijacked by the virus. They used cells from the epithelium, or surface, of the lung’s tree-like airways, taken from transplanted lungs, and grew them in the lab. Then they exposed the cells to the coronavirus, officially dubbed SARS-CoV-2, and let nature take over from there. The infection experiments all took in a Biosafety Level 3 lab, reserved for studying some of the most dangerous germs in the world.

Viruses are essentially a tiny package of proteins and genetic material (either DNA or RNA, as with SARS-CoV-2) that break into and hijack living cells. Then they force these infected cells to produce and send out more copies of themselves into the world, which starts the process all over again. Usually, this process eventually leads to the death of the cell itself. Viruses are so dependent on other organisms that it’s still a fierce debate among scientists on whether they should be considered a living thing or not.

The images above and below show individual fully intact copies of the virus, called virons, roaming free around the airway cells 96 hours post-infection. They were taken under a scanning electron microscope (SEM), which is needed to see incredibly small things like viruses. The ball-looking things are SARS-CoV-2, while the bendy churro-looking structures are cells with cilia, the hair-like projections that move in rhythm to clear debris, mucus and microbes from the airways, allowing us to breathe normally. Ehre found that SARS-CoV-2 was particularly fond of infecting these cililated cells, and that once it did, it went to town making more of itself.

![[IMG] [IMG]](https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/c_scale,f_auto,fl_progressive,pg_1,q_80,w_1600/sn9njzbv21ahflknmh3f.png)

An image of SARS-COV-2 virions infecting the cells that line the airways of our lungs. This image is at 100 nanometers, or 10 times closer than the top image. Image: Camille Ehre/The New England Journal of Medicine ©2020

“When we looked at these infected cultures under an SEM microscope, the most striking observation was the astonishing number of virions produced by a single infected cell,” Ehre said over email. “Some of these infected cells were so engorged with viruses that they rounded up and detached from the epithelium, giving the impression that they were about to burst.”

The high levels of SARS-CoV-2 produced by airway cells (a 3-to-1 ratio in the study) aptly helps explain why the coronavirus can so greatly affect different parts of the body nearby, like the lining of our nasal cavity, which is crucial to our sense of smell, according to Ehre.

“A huge viral load is available to spread within an infected individual and infect the olfactory epithelium, explaining the common symptom of loss of smell, and also infect the salivary glands, which would explain the symptom of dry mouth,” she said. “The worst is when viruses go to the lungs and produce pneumonia that causes shortness of breath and ultimately can lead to death.”

These sorts of findings are important for filling in a piece of the scientific puzzle that is SARS-CoV-2 and covid-19. But for the average person, they might serve as more motivation to keep yourself and others as safe from infection as possible.

“These images of SARS-CoV-2 infected cultures showing ciliated cells jam-packed with viruses releasing large clumps of virus particles make a strong case for the use of masks by infected and uninfected individuals to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission,” Ehre said.

Personally, the last thing I want is those dirty-looking cotton balls from hell doing the above to my lungs.

![[IMG] [IMG]](https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/c_scale,f_auto,fl_progressive,pg_1,q_80,w_1600/hnub90oz0rwps87etlol.png)

An image of SARS-COV-2 virions infecting the cells that line the airways of our lungs. The image is taken at 1 micrometer magnification.

Image: Camille Ehre/The New England Journal of Medicine ©2020

Horrifying Images Show How the Coronavirus Ravages Our Lungs

Here’s a closer look at the coronavirus that causes covid-19, courtesy of new research published in the New England Journal of Medicine Thursday. These images depicting the coronavirus en masse infecting human lung cells aren’t just for show either—they might just provide a hint as to why covid-19 can be so devastating to our bodies.

Camille Ehre, a pediatric pulmonologist and lung researcher at the University of North Carolina, and her team created the photo opportunity to understand exactly how the coronavirus interacts with the lung’s airways upon infection, as well as how these infected cells behaved once they were hijacked by the virus. They used cells from the epithelium, or surface, of the lung’s tree-like airways, taken from transplanted lungs, and grew them in the lab. Then they exposed the cells to the coronavirus, officially dubbed SARS-CoV-2, and let nature take over from there. The infection experiments all took in a Biosafety Level 3 lab, reserved for studying some of the most dangerous germs in the world.

Viruses are essentially a tiny package of proteins and genetic material (either DNA or RNA, as with SARS-CoV-2) that break into and hijack living cells. Then they force these infected cells to produce and send out more copies of themselves into the world, which starts the process all over again. Usually, this process eventually leads to the death of the cell itself. Viruses are so dependent on other organisms that it’s still a fierce debate among scientists on whether they should be considered a living thing or not.

The images above and below show individual fully intact copies of the virus, called virons, roaming free around the airway cells 96 hours post-infection. They were taken under a scanning electron microscope (SEM), which is needed to see incredibly small things like viruses. The ball-looking things are SARS-CoV-2, while the bendy churro-looking structures are cells with cilia, the hair-like projections that move in rhythm to clear debris, mucus and microbes from the airways, allowing us to breathe normally. Ehre found that SARS-CoV-2 was particularly fond of infecting these cililated cells, and that once it did, it went to town making more of itself.

![[IMG] [IMG]](https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/c_scale,f_auto,fl_progressive,pg_1,q_80,w_1600/sn9njzbv21ahflknmh3f.png)

An image of SARS-COV-2 virions infecting the cells that line the airways of our lungs. This image is at 100 nanometers, or 10 times closer than the top image. Image: Camille Ehre/The New England Journal of Medicine ©2020

“When we looked at these infected cultures under an SEM microscope, the most striking observation was the astonishing number of virions produced by a single infected cell,” Ehre said over email. “Some of these infected cells were so engorged with viruses that they rounded up and detached from the epithelium, giving the impression that they were about to burst.”

The high levels of SARS-CoV-2 produced by airway cells (a 3-to-1 ratio in the study) aptly helps explain why the coronavirus can so greatly affect different parts of the body nearby, like the lining of our nasal cavity, which is crucial to our sense of smell, according to Ehre.

“A huge viral load is available to spread within an infected individual and infect the olfactory epithelium, explaining the common symptom of loss of smell, and also infect the salivary glands, which would explain the symptom of dry mouth,” she said. “The worst is when viruses go to the lungs and produce pneumonia that causes shortness of breath and ultimately can lead to death.”

These sorts of findings are important for filling in a piece of the scientific puzzle that is SARS-CoV-2 and covid-19. But for the average person, they might serve as more motivation to keep yourself and others as safe from infection as possible.

“These images of SARS-CoV-2 infected cultures showing ciliated cells jam-packed with viruses releasing large clumps of virus particles make a strong case for the use of masks by infected and uninfected individuals to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission,” Ehre said.

Personally, the last thing I want is those dirty-looking cotton balls from hell doing the above to my lungs.

Last edited: