It's gonna pop soon after October's 19th Congress.

China Is Playing a $9 Trillion Game of Chicken With Savers

WMPs have proliferated thanks to implicit state guarantees

Government wants to reduce moral hazard, but it won’t be easy

Like many individual investors in China, Yang Mo has no idea what’s in the wealth management products that make up a big chunk of her net worth.

She says there’s really no point in finding out. Sure, WMPs invest in all kinds of risky assets, but the government would never let a big one fail, she says.

“It’s not how the Chinese government does things, and it’s not even Chinese culture,” explains Yang, a 29-year-old public relations professional in Beijing.

Hers is a common refrain in Asia’s largest economy, where savers have poured $9 trillion into WMPs and similar products on the assumption that they’ll get bailed out if the investments sour. Even after news in February that policy makers are drafting rules to make it clear that state guarantees don’t exist, Yang is undaunted. She says she’ll only withdraw money from WMPs in the unlikely event that they start to suffer losses.

“Cracking down on implicit guarantees is just like curbing home prices,” she says. “It’s something that the government needs to say, but it’s not something they will eventually do.”

Yang’s steadfast faith in bailouts illustrates the dilemma for authorities as they try to reduce moral hazard and improve the pricing of risk in China’s financial system: It may require a major WMP blowup to shake investors out of their complacency, an event that could wreak havoc on banks that increasingly rely on the products for funding.

“Only after a WMP defaults in a high-profile way will investors start worrying about their money,” says Hao Hong, a Hong Kong-based strategist at Bocom International Holdings Co. who’s known for his prescient calls on Chinese markets.

While Hong characterizes the proliferation of WMPs as a “bubble” that will eventually burst, he says imminent losses are unlikely because policy makers are focused on maintaining market stability before a leadership reshuffle at the end of 2017.

Still, that doesn’t mean it will be smooth sailing this year. WMPs -- a key part of China’s shadow banking system -- are getting squeezed as the nation’s central bank increases interest rates to discourage excessive leverage. That’s not only putting pressure on products that use borrowed funds to meet their fixed return targets, it’s also weighing on the Chinese bond market, where WMPs allocate the biggest portion of their funds.

For as long as they can, banks will make investors whole when WMPs run into trouble because they fear the reputational damage of a failed product, according to Hong. At some point, though, WMP shortfalls may be too large for the banks to cover, forcing policy makers to decide whether they’re willing to allow losses.

Intervention is becoming less likely, if the new draft rules are anything to go by. Regulators are working on language that would make clear there are no state guarantees on asset-management products -- which include WMPs, trusts, mutual funds and other products -- people familiar with the matter said in February.

On Monday, the China Banking Regulatory Commission issued risk management guidelines for lenders that included a section on WMPs. The regulator said the products should be simple and transparent, avoid excessive leverage and invest in distinct assets -- rather than pooling funds with other WMPs. Banks should only steer customers into products that are appropriate for their risk tolerance, the CBRC added.

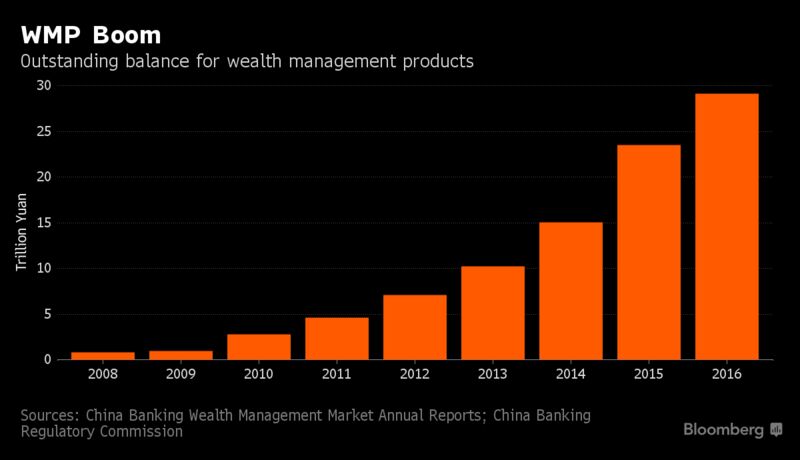

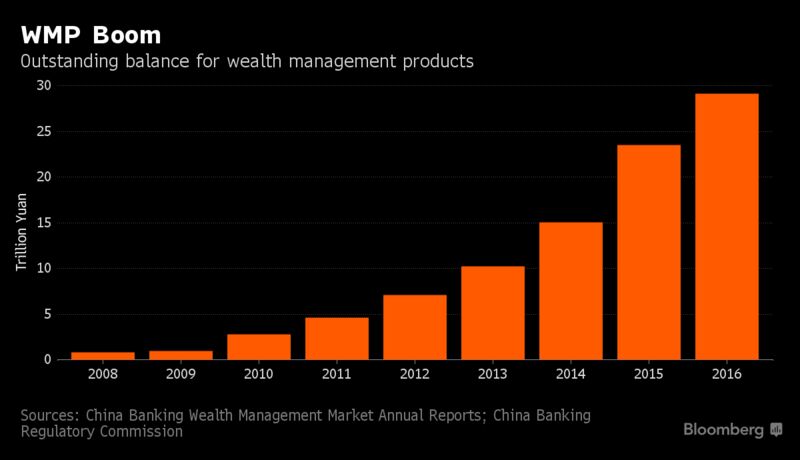

The investments’ sheer size shows why Beijing is keen to quash the notion of a government backstop. Assets in AMPs amounted to about 80 percent of China’s gross domestic product as of June, data compiled by the China Securities Regulatory Commission and Bloomberg show.

WMPs are the biggest category of AMPs, with assets of around 29.1 trillion yuan ($4.2 trillion) at the end of December, according to the CBRC. They’re also the products most widely viewed as risk free by Chinese savers.

It’s easy to see why. Despite investing in volatile assets from corporate bonds to stocks and real estate, WMPs have produced remarkably steady returns. Among the more than 181,000 products that matured in 2015, just 44 suffered a loss, most of which were sold by foreign banks. WMPs issued last week advertised an average annualized return of about 4.3 percent, according to Chengdu-based research firm PY Standard, versus the benchmark one-year deposit rate of 1.5 percent.

While public evidence of WMP bailouts is scarce, the People’s Bank of China has said that when products struggle to meet their return targets, the banks that distribute them often make up the shortfall. Most of the nation’s biggest lenders are majority-owned by China’s government.

“Major banks appear to have sufficient capabilities to offset the potential losses," says Weiwei Fang, 35, who works at a consulting firm in Shanghai and keeps about 90 percent of her personal savings in WMPs. “At least I think my principal should be safe."

The PBOC, the CSRC and the CBRC didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Even Michelle He, a 30-year-old client manager at a state-owned bank in Sichuan province, says her faith in WMPs has limits. He, who buys the products on her mobile phone, says she’s confident that banks or the government will step in to prevent failures, but concedes that any sign of losses in WMPs would prompt her to pull out.

The challenge for policy makers is to create an environment where troubled WMPs can inflict losses on investors without sparking a mass exodus. The government’s most likely approach is to let loss-making WMPs fail, before stepping in to contain the fallout, according to Andrew Collier, managing director at Orient Capital Research and author of a book on shadow banking. That could result in a “limited financial crisis” centered on smaller banks, he says, adding that some institutions would likely be recapitalized by the government or merged with larger peers.

As for the Chinese savers who lose their money, Collier says it would be an important learning experience. “Shadow banking has been a great lesson in capitalism and it has allowed many Chinese to learn how to manage their money in a free-market environment,” he says. “However, the real lessons about the risks of capitalism have yet to be learned by the average investor.”

China Is Playing a $9 Trillion Game of Chicken With Savers

WMPs have proliferated thanks to implicit state guarantees

Government wants to reduce moral hazard, but it won’t be easy

Like many individual investors in China, Yang Mo has no idea what’s in the wealth management products that make up a big chunk of her net worth.

She says there’s really no point in finding out. Sure, WMPs invest in all kinds of risky assets, but the government would never let a big one fail, she says.

“It’s not how the Chinese government does things, and it’s not even Chinese culture,” explains Yang, a 29-year-old public relations professional in Beijing.

Hers is a common refrain in Asia’s largest economy, where savers have poured $9 trillion into WMPs and similar products on the assumption that they’ll get bailed out if the investments sour. Even after news in February that policy makers are drafting rules to make it clear that state guarantees don’t exist, Yang is undaunted. She says she’ll only withdraw money from WMPs in the unlikely event that they start to suffer losses.

“Cracking down on implicit guarantees is just like curbing home prices,” she says. “It’s something that the government needs to say, but it’s not something they will eventually do.”

Yang’s steadfast faith in bailouts illustrates the dilemma for authorities as they try to reduce moral hazard and improve the pricing of risk in China’s financial system: It may require a major WMP blowup to shake investors out of their complacency, an event that could wreak havoc on banks that increasingly rely on the products for funding.

“Only after a WMP defaults in a high-profile way will investors start worrying about their money,” says Hao Hong, a Hong Kong-based strategist at Bocom International Holdings Co. who’s known for his prescient calls on Chinese markets.

While Hong characterizes the proliferation of WMPs as a “bubble” that will eventually burst, he says imminent losses are unlikely because policy makers are focused on maintaining market stability before a leadership reshuffle at the end of 2017.

Still, that doesn’t mean it will be smooth sailing this year. WMPs -- a key part of China’s shadow banking system -- are getting squeezed as the nation’s central bank increases interest rates to discourage excessive leverage. That’s not only putting pressure on products that use borrowed funds to meet their fixed return targets, it’s also weighing on the Chinese bond market, where WMPs allocate the biggest portion of their funds.

For as long as they can, banks will make investors whole when WMPs run into trouble because they fear the reputational damage of a failed product, according to Hong. At some point, though, WMP shortfalls may be too large for the banks to cover, forcing policy makers to decide whether they’re willing to allow losses.

Intervention is becoming less likely, if the new draft rules are anything to go by. Regulators are working on language that would make clear there are no state guarantees on asset-management products -- which include WMPs, trusts, mutual funds and other products -- people familiar with the matter said in February.

On Monday, the China Banking Regulatory Commission issued risk management guidelines for lenders that included a section on WMPs. The regulator said the products should be simple and transparent, avoid excessive leverage and invest in distinct assets -- rather than pooling funds with other WMPs. Banks should only steer customers into products that are appropriate for their risk tolerance, the CBRC added.

The investments’ sheer size shows why Beijing is keen to quash the notion of a government backstop. Assets in AMPs amounted to about 80 percent of China’s gross domestic product as of June, data compiled by the China Securities Regulatory Commission and Bloomberg show.

WMPs are the biggest category of AMPs, with assets of around 29.1 trillion yuan ($4.2 trillion) at the end of December, according to the CBRC. They’re also the products most widely viewed as risk free by Chinese savers.

It’s easy to see why. Despite investing in volatile assets from corporate bonds to stocks and real estate, WMPs have produced remarkably steady returns. Among the more than 181,000 products that matured in 2015, just 44 suffered a loss, most of which were sold by foreign banks. WMPs issued last week advertised an average annualized return of about 4.3 percent, according to Chengdu-based research firm PY Standard, versus the benchmark one-year deposit rate of 1.5 percent.

While public evidence of WMP bailouts is scarce, the People’s Bank of China has said that when products struggle to meet their return targets, the banks that distribute them often make up the shortfall. Most of the nation’s biggest lenders are majority-owned by China’s government.

“Major banks appear to have sufficient capabilities to offset the potential losses," says Weiwei Fang, 35, who works at a consulting firm in Shanghai and keeps about 90 percent of her personal savings in WMPs. “At least I think my principal should be safe."

The PBOC, the CSRC and the CBRC didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Even Michelle He, a 30-year-old client manager at a state-owned bank in Sichuan province, says her faith in WMPs has limits. He, who buys the products on her mobile phone, says she’s confident that banks or the government will step in to prevent failures, but concedes that any sign of losses in WMPs would prompt her to pull out.

The challenge for policy makers is to create an environment where troubled WMPs can inflict losses on investors without sparking a mass exodus. The government’s most likely approach is to let loss-making WMPs fail, before stepping in to contain the fallout, according to Andrew Collier, managing director at Orient Capital Research and author of a book on shadow banking. That could result in a “limited financial crisis” centered on smaller banks, he says, adding that some institutions would likely be recapitalized by the government or merged with larger peers.

As for the Chinese savers who lose their money, Collier says it would be an important learning experience. “Shadow banking has been a great lesson in capitalism and it has allowed many Chinese to learn how to manage their money in a free-market environment,” he says. “However, the real lessons about the risks of capitalism have yet to be learned by the average investor.”