Conflicting Arguments arise again and again among doctors these days. They are NOT SURE actually how medicine and bacterial works! If you are ill you are screwed! You are not too far from doomed!

http://edition.cnn.com/2017/07/27/health/antibiotics-course-advice-study/index.html

Researchers question whether you should really finish your antibiotics

By Zamira Rahim, CNN

Updated 1354 GMT (2154 HKT) July 27, 2017

How bugs become superbugs

How bugs become superbugs

How bugs become superbugs 00:58

Story highlights

A group of experts suggests traditional advice on completing antibiotics could do more harm than good

Other doctors say it's too early to urge patients to change behavior on antibiotics

(CNN)The standing argument that failing to complete a course of antibiotics could fuel the rise of antibiotic resistance has little evidence, a group of United Kingdom researchers argue in a new paper. In an analysis published in the medical journal the BMJ on Thursday, they say that completing a course of antibiotics may instead increase the risk of resistance.

The "complete the course" advice given to patients taking antibiotics is "fallacious" and backed by little evidence, they state in their article, and could lead to antibiotic overuse -- and further resistance.

But other doctors urge caution, and say they aren't ready to change standard advice around taking antibiotics.

5 things you need to know about antimicrobial resistance

5 things you need to know about antimicrobial resistance

The opinion piece suggests that an alternative message, such as "stop when you feel better" could be developed. But the authors accept that more research is needed before this is implemented -- and that this may not apply to all infections.

"We're not at all saying that patients should stop when they feel like it or that patients should ignore their doctor's advice," Tim Peto, professor of medicine at the University of Oxford and a co-author of the article, told CNN.

But Peto believes that ending a course of antibiotics to prevent resistance is a counter-intuitive view and that there is "not enough knowledge" for doctors to know how long antibiotics should be prescribed for.

This STD is becoming 'smarter' and harder to treat

This STD is becoming 'smarter' and harder to treat

Current advice to complete your course of antibiotics stems from the early days of antibiotic use, the authors describe. They note that Alexander Fleming's Nobel speech in 1945 includes a vivid story of an imagined patient who takes an insufficient amount of penicillin, leading to a death in another patient who is infected and becomes resistant. "If you use penicillin, use enough," Fleming urged in the speech.

"No one has questioned (this advice) for all this time," said Peto.

"In the scientific world, it's an accepted view that there is too much usage of antibiotics and we want to minimize that. We want to only give them to people who need antibiotics to get better," he said.

The paper then concludes that the public should be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved.

But the group's stance has received mixed responses from the medical community.

Don't change behavior just yet

The Royal College of General Practitioners, a network of more than 52,000 family doctors in the UK, urged caution.

See for yourself: A giant petri dish models antibiotic resistance

See for yourself: A giant petri dish models antibiotic resistance

"It's important that we take new evidence around how to curb this on board, but we cannot advocate widespread behavior change on the results of just one study," said Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, the group's chairwoman, in a statement.

Stokes-Lampard recommended that the public should continue following "complete the course" advice until more is known. "We would urge our patients not to change their behavior," she said, adding that changing the accepted "mantra" would "simply confuse people."

But she agreed that more clinical trials are needed to understand more about whether courses should be completed, and that people should then take any new evidence into account when guidelines are updated. "We're not at that stage yet," she warned.

The UK's National Health Service says antibiotic resistance is a significant threat to patient safety and both the NHS and World Health Organization presently advise people to complete their antibiotic courses.

But Jodi Lindsay, professor of microbial pathogenesis at St. George's, University of London, believes this new advice -- to stop taking antibiotics once you feel better -- is "sensible."

"The evidence for 'completing the course' is poor, and the length of the course of antibiotics has been estimated based on a fear of under-treating rather than any studies," she said, adding that there are a few exceptions of diseases when longer treatment courses are better, such as tuberculosis, which has a minimum treatment period of six months.

Join the conversation

See the latest news and share your comments with CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter.

"It remains astonishing that apart from some specific infections and conditions, we still do not know more about the optimum duration of courses or indeed doses in many conditions," added Alison Holmes, professor of infectious diseases at Imperial College London. "Yet this dogma [to complete the course] has been pervasive and persistent."

Peto said more high-quality research is being done on the topic by experts within the field.

"The more one looks, the more we see that we can shorten the duration [of a prescription's length]," he said.

They're trying to avoid blanket statements because of illness such as tuberculosis, he said, but that illness is unusual.

"With normal family practice infections, we just don't know what the optimum length of time is that a patient should [take antibiotics for]," he said.

"What we want is to empower general practitioners to be able to shorten courses on a case-by-case basis if they feel that it's best for the patient."

http://www.newsweek.com/myth-antibiotics-complete-course-wont-stop-resistance-642476

Tech & Science

The Myth of Antibiotics: ‘Complete the Course’ Won’t Stop Resistance, Researchers Say

By Michele Gorman On 7/26/17 at 6:30 PM

Tech & Science

Antibiotics

antibiotic resistance

Doctors have long urged patients to adhere strictly to antibiotic prescriptions, asserting that the entire course should be completed regardless of whether their symptoms have been resolved. Not doing so, conventional wisdom has held, brings the risk of increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most serious global threats to both human health and agriculture, and finding ways to avoid it is a priority. When it comes to treatment for our bacterial infections, it has long been thought that cutting a course short eradicates most but not all of the bacteria behind the illness, thus leaving the door open for the pathogens to develop the ability to evade attack by the drugs.

Recently, that approach has been called into question. Most notably, Louise Rice, who chairs the department of medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University, has led the movement to re-examine this directive. Now, this paradigm shift has taken yet another step. In a newly published issue of BMJ, a major medical journal, researchers argue that telling patients to complete a full course of antibiotics to avoid resistance is not backed by evidence.

Tech & Science Emails and Alerts - Get the best of Newsweek Tech & Science delivered to your inbox

Related: After years of debate, the FDA curtails antibiotic use in livestock

In fact, Martin Llewelyn and his colleagues at Brighton and Sussex Medical School in the United Kingdom say in the paper there is evidence that, in many situations, stopping antibiotics sooner is a safe and effective way to reduce overuse, while taking antibiotics for longer than necessary increases the risk of resistance.

0726_antibiotic_resistance_study_01 Amoxicillin penicillin antibiotics are seen in a pharmacy at a free medical and dental health clinic in Los Angeles on April 27, 2016. Researchers in a new study urge doctors, educators and policy makers to drop the deeply embedded “complete the course” message. Lucy Nicholson/Reuters

The researchers urge doctors, educators and policy makers to drop the “complete the course” message and communicate with patients that the longstanding way of thinking is incorrect. For common bacterial infections, for example, no evidence exists that stopping antibiotic treatment early increases a patient’s risk of resistant infection.

“We found that the common advice that it is ‘important for patients to finish their course of antibiotics in order to avoid the emergence of antibiotic resistance’ appears to be a modern myth, deeply embedded in our culture but based on no sound scientific evidence,” Tim Peto, professor of infectious diseases at the NIHR Biomedical Research Center, Oxford University the medical school, tells Newsweek.

Their main argument for changing how doctors discuss antibiotic courses with patients is that shorter treatment can be better for individual patients. Not only does an individual patient’s risk of resistant infection depend on his/her previous antibiotic exposure, but reducing that exposure via shorter treatment is associated with reduced risk of resistant infection and better clinical outcome, they say.

As the authors note, antibiotics are vital to modern medicine and resistance is a global, urgent threat to human health. But completing a course, they add, defies one of the most fundamental and widespread medication beliefs: that we should take as little medication as necessary.

Traditionally, antibiotics are prescribed for recommended durations or courses. Fundamental to the concept of an antibiotic course is the notion that shorter treatment will be inferior.

Concern that giving too little antibiotic treatment could select for resistance can be traced back to 1941, when Howard Florey’s team treated Albert Alexander’s staphylococcal sepsis with penicillin. They stretched out all the penicillin they had over four days by repeatedly recovering the drug from the patient’s urine. When the drug ran out, the clinical improvement they had noted reversed, and he subsequently succumbed to his infection. As the researchers note in their new study, there was no evidence that this was because of resistance, but the experience may have planted the idea that prolonged therapy was needed to avoid treatment failure.

More recently, in materials supporting Antibiotic Awareness Week 2016, the World Health Organization advised patients to “always complete the full prescription, even if you feel better, because stopping treatment early promotes the growth of drug-resistant bacteria.” Similar advice appears in national campaigns in Australia, Canada, the United States and throughout Europe. In the U.K., it’s included as fact in the curriculum for secondary school children, the authors note.

They also note there are exceptions for some types of antibiotics, including those used to treat tuberculosis.

They call for research to determine the most appropriate, simple alternative messages, such as stop when you feel better, and advise policy makers to publicly and actively state that the old message was not evidence-based and is incorrect. Clinical trials are required to determine the most effective strategies for optimizing duration of antibiotic treatment.

“The public,” they add, “should also be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved by tailoring treatment duration for individual patients.”

http://gizmodo.com/doctors-slam-new-recommendation-that-we-should-stop-ant-1797301481

Doctors Slam New Recommendation That We Should Stop Antibiotic Treatments Early

George Dvorsky

Today 1:15pmFiled to: ANTIBIOTICS

50

6

Image: Rob Brewer/Flickr

Scientists from the UK caused quite a stir this week, when they announced that we don’t necessarily need to complete a full course of antibiotics in order to treat infections properly. It’s a provocative message, but skeptics say their advice is grossly premature—and even reckless.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is not caused by putting an early stop to a prescribed course of antibiotics, but by antibiotic overuse, argue a team of infectious disease experts in The British Medical Journal. The team, led by Martin Llewelyn of the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, is asking doctors, educators, and policy makers to “stop advocating ‘complete the course’ when communicating with the public.”

Which, wow. This is a complete turn-around from what we’ve been told for years—that we need to finish our bottles right down to the last pill in order to properly treat our infections and prevent the proliferation of microbial resistant bacteria. According to these experts, we’ve been wrong about this, and what’s more, the “complete the course” culture may be responsible for the rapid decline in antibiotic effectiveness.

But the experts Gizmodo spoke to said the BMJ opinion piece, while important, may be sending the wrong message. They say a lot more research needs to be done before doctors can confidently start telling their patients to ease off their medications, and that the sweeping statement presented by the BMJ researchers fails to take the complex, multi-faceted nature of bacterial infections into account. In a word, they described the opinion piece as “dangerous.”

“The public should be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved.”

Llewelyn and his colleagues say the convention of prescribing long treatments is based on an outdated notion.

“Traditionally, antibiotics are prescribed for recommended durations or courses,” write the BMJ authors. “Fundamental to the concept of an antibiotic course is the notion that shorter treatment will be inferior. There is, however, little evidence that currently recommended durations are minimums, below which patients will be at increased risk of treatment failure.” Today’s prescription culture, they argue, is “driven by fear of undertreatment, with less concern about overuse.”

At the same time, the authors say there’s growing evidence that short course antibiotics—treatments lasting just three to five days—work just as effectively in treating an assortment of bacterial infections, and that we should move away from “blanket” prescriptions. But Llewelyn and his colleagues admit there are exceptions, citing the need to prescribe more than one type of antibiotic to TB infections, which are notorious for developing resistance.

The authors also admit it’s not going to be easy to change the culture, as the idea of taking a full course of antibiotics is “deeply embedded, and both doctors and patients currently regard failure to complete a course of antibiotics as “irresponsible behaviour.” But Llewelyn’s team is optimistic that the public will accept short-duration treatments if the medical profession openly acknowledges this shift in opinion, and that the public “be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved.”

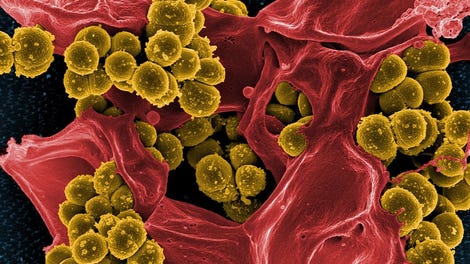

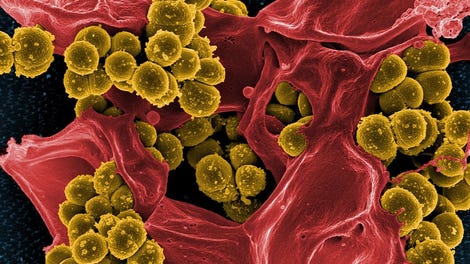

Skin bacteria. (Image: AP)

“I think the article is exciting, for so many practices in medicine it’s important to ask the origins and whether they are helping or harming patients,” said Harvard Medical School researcher Michael Baym, an expert in antibiotic resistance who wasn’t involved with the BMJ opinion piece. “The article establishes very well that the traditional seven-day course of antibiotic is not well founded, and that, consistent with evolutionary theory, a longer course does not lessen the emergence of resistance.”

That said, Baym says that replacing the general advice to finish a course with general advice to not finish a course is likewise based on insufficient evidence.

“I think the real conclusion is that we need to get away from the idea that all antibiotics and all infections require uniform thinking, and instead do specific studies to find out ideal treatment regimens for specific infections and specific antibiotics,” Baym told Gizmodo.

Maha R. Farhat, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Informatics at Harvard Medical School, agrees with Baym, saying the authors made an ambitious statement that isn’t currently founded in sufficient evidence.

“Most infectious disease doctors and antibiotic resistance specialists would like to see less use of antibiotics but the reality is that we we don’t yet have enough evidence to throw a blanket statement as the authors did,” Farhat told Gizmodo. “It’s true that collateral resistance is an issue, but what this should call for is more research and not a premature change in public health recommendations and awareness campaigns as the authors suggest.”

Farhat says the authors also failed to discuss evidence showing that antibiotic noncompliance—i.e. not necessarily shorter therapy, but interrupted therapy—is a key driver of resistance in both the patient and the larger population.

“Doctors, including myself, often emphasize the ‘take as prescribed’ statement because of a larger fear of the former [the patient]—which is more likely—than the latter [the larger population, or collateral resistance].”

Vaughn Cooper, a microbiologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, says we most certainly need to reconsider the the “one-size-fits-all” approach to antibiotic prescriptions, but he describes the new editorial as being “clearly dangerous.”

“Arguing that antibiotic course duration is not sufficiently evidence-based is worthwhile, but the editorial essentially argues that patients should not finish their course of antibiotics,” Cooper told Gizmodo. “This, too, is not evidence-based and increases the likelihood of adverse outcomes for patients disregarding medical advice when a course of antibiotics is clearly warranted.”

Article preview thumbnail

This Is Why You Shouldn’t Cut Your Kid’s Ear Infection Treatment Short

Some parents, wary of antibiotics, often cut their child’s ear infection treatments short. A new…

Read more

Cooper says the BMJ authors conveniently ignored what scientists already knew about antibiotics in terms of duration and efficacy, pointing to a New England Journal of Medicine study from last year showing that standard duration treatments—some lasting as long as ten days—do not increase a child’s level of antibiotic resistance (at least for kids with ear infections), and that children who are taken off antibiotics early exhibit worse outcomes.

“Suggesting patients not complete the recommended treatment course...is hazardous, for several reasons,” said Yonatan H. Grad, Assistant Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. “Not all infections are the same. For some infections, like TB, it is critically important to complete the treatment course, because, as has been demonstrated all too many times, not doing so promotes antimicrobial resistance in TB and recurrence of infection.”

Grad takes issue with the paper’s suggestion that patients stop taking antibiotics when they start to “feel better,” saying it’s too vague and subjective a recommendation. He also worries that a growing batch of unfinished bottles in the medicine cabinet will promote the inappropriate use of antibiotics, and have the exact opposite effect of what was intended.

“The critical problem of antimicrobial resistance should encourage us to revisit how we approach antibiotic use, as there are many opportunities for improvement,” Grad told Gizmodo. “As this opinion piece suggests, we need more clinical trials to determine the effectiveness of shorter duration treatments.”

Until that happens, you’d best finish your medications “as prescribed.”

[BMJ]

Recommended Stories

Antibiotic-Resistant Superbugs Could Kill 10 Million People a Year By 2050

Watch as Bacteria Evolve Antibiotic Resistance in a Gigantic Petri Dish

Electron microscope shows bacterial eating human:

http://edition.cnn.com/2017/07/27/health/antibiotics-course-advice-study/index.html

Researchers question whether you should really finish your antibiotics

By Zamira Rahim, CNN

Updated 1354 GMT (2154 HKT) July 27, 2017

How bugs become superbugs

How bugs become superbugs

How bugs become superbugs 00:58

Story highlights

A group of experts suggests traditional advice on completing antibiotics could do more harm than good

Other doctors say it's too early to urge patients to change behavior on antibiotics

(CNN)The standing argument that failing to complete a course of antibiotics could fuel the rise of antibiotic resistance has little evidence, a group of United Kingdom researchers argue in a new paper. In an analysis published in the medical journal the BMJ on Thursday, they say that completing a course of antibiotics may instead increase the risk of resistance.

The "complete the course" advice given to patients taking antibiotics is "fallacious" and backed by little evidence, they state in their article, and could lead to antibiotic overuse -- and further resistance.

But other doctors urge caution, and say they aren't ready to change standard advice around taking antibiotics.

5 things you need to know about antimicrobial resistance

5 things you need to know about antimicrobial resistance

The opinion piece suggests that an alternative message, such as "stop when you feel better" could be developed. But the authors accept that more research is needed before this is implemented -- and that this may not apply to all infections.

"We're not at all saying that patients should stop when they feel like it or that patients should ignore their doctor's advice," Tim Peto, professor of medicine at the University of Oxford and a co-author of the article, told CNN.

But Peto believes that ending a course of antibiotics to prevent resistance is a counter-intuitive view and that there is "not enough knowledge" for doctors to know how long antibiotics should be prescribed for.

This STD is becoming 'smarter' and harder to treat

This STD is becoming 'smarter' and harder to treat

Current advice to complete your course of antibiotics stems from the early days of antibiotic use, the authors describe. They note that Alexander Fleming's Nobel speech in 1945 includes a vivid story of an imagined patient who takes an insufficient amount of penicillin, leading to a death in another patient who is infected and becomes resistant. "If you use penicillin, use enough," Fleming urged in the speech.

"No one has questioned (this advice) for all this time," said Peto.

"In the scientific world, it's an accepted view that there is too much usage of antibiotics and we want to minimize that. We want to only give them to people who need antibiotics to get better," he said.

The paper then concludes that the public should be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved.

But the group's stance has received mixed responses from the medical community.

Don't change behavior just yet

The Royal College of General Practitioners, a network of more than 52,000 family doctors in the UK, urged caution.

See for yourself: A giant petri dish models antibiotic resistance

See for yourself: A giant petri dish models antibiotic resistance

"It's important that we take new evidence around how to curb this on board, but we cannot advocate widespread behavior change on the results of just one study," said Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, the group's chairwoman, in a statement.

Stokes-Lampard recommended that the public should continue following "complete the course" advice until more is known. "We would urge our patients not to change their behavior," she said, adding that changing the accepted "mantra" would "simply confuse people."

But she agreed that more clinical trials are needed to understand more about whether courses should be completed, and that people should then take any new evidence into account when guidelines are updated. "We're not at that stage yet," she warned.

The UK's National Health Service says antibiotic resistance is a significant threat to patient safety and both the NHS and World Health Organization presently advise people to complete their antibiotic courses.

But Jodi Lindsay, professor of microbial pathogenesis at St. George's, University of London, believes this new advice -- to stop taking antibiotics once you feel better -- is "sensible."

"The evidence for 'completing the course' is poor, and the length of the course of antibiotics has been estimated based on a fear of under-treating rather than any studies," she said, adding that there are a few exceptions of diseases when longer treatment courses are better, such as tuberculosis, which has a minimum treatment period of six months.

Join the conversation

See the latest news and share your comments with CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter.

"It remains astonishing that apart from some specific infections and conditions, we still do not know more about the optimum duration of courses or indeed doses in many conditions," added Alison Holmes, professor of infectious diseases at Imperial College London. "Yet this dogma [to complete the course] has been pervasive and persistent."

Peto said more high-quality research is being done on the topic by experts within the field.

"The more one looks, the more we see that we can shorten the duration [of a prescription's length]," he said.

They're trying to avoid blanket statements because of illness such as tuberculosis, he said, but that illness is unusual.

"With normal family practice infections, we just don't know what the optimum length of time is that a patient should [take antibiotics for]," he said.

"What we want is to empower general practitioners to be able to shorten courses on a case-by-case basis if they feel that it's best for the patient."

http://www.newsweek.com/myth-antibiotics-complete-course-wont-stop-resistance-642476

Tech & Science

The Myth of Antibiotics: ‘Complete the Course’ Won’t Stop Resistance, Researchers Say

By Michele Gorman On 7/26/17 at 6:30 PM

Tech & Science

Antibiotics

antibiotic resistance

Doctors have long urged patients to adhere strictly to antibiotic prescriptions, asserting that the entire course should be completed regardless of whether their symptoms have been resolved. Not doing so, conventional wisdom has held, brings the risk of increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most serious global threats to both human health and agriculture, and finding ways to avoid it is a priority. When it comes to treatment for our bacterial infections, it has long been thought that cutting a course short eradicates most but not all of the bacteria behind the illness, thus leaving the door open for the pathogens to develop the ability to evade attack by the drugs.

Recently, that approach has been called into question. Most notably, Louise Rice, who chairs the department of medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University, has led the movement to re-examine this directive. Now, this paradigm shift has taken yet another step. In a newly published issue of BMJ, a major medical journal, researchers argue that telling patients to complete a full course of antibiotics to avoid resistance is not backed by evidence.

Tech & Science Emails and Alerts - Get the best of Newsweek Tech & Science delivered to your inbox

Related: After years of debate, the FDA curtails antibiotic use in livestock

In fact, Martin Llewelyn and his colleagues at Brighton and Sussex Medical School in the United Kingdom say in the paper there is evidence that, in many situations, stopping antibiotics sooner is a safe and effective way to reduce overuse, while taking antibiotics for longer than necessary increases the risk of resistance.

0726_antibiotic_resistance_study_01 Amoxicillin penicillin antibiotics are seen in a pharmacy at a free medical and dental health clinic in Los Angeles on April 27, 2016. Researchers in a new study urge doctors, educators and policy makers to drop the deeply embedded “complete the course” message. Lucy Nicholson/Reuters

The researchers urge doctors, educators and policy makers to drop the “complete the course” message and communicate with patients that the longstanding way of thinking is incorrect. For common bacterial infections, for example, no evidence exists that stopping antibiotic treatment early increases a patient’s risk of resistant infection.

“We found that the common advice that it is ‘important for patients to finish their course of antibiotics in order to avoid the emergence of antibiotic resistance’ appears to be a modern myth, deeply embedded in our culture but based on no sound scientific evidence,” Tim Peto, professor of infectious diseases at the NIHR Biomedical Research Center, Oxford University the medical school, tells Newsweek.

Their main argument for changing how doctors discuss antibiotic courses with patients is that shorter treatment can be better for individual patients. Not only does an individual patient’s risk of resistant infection depend on his/her previous antibiotic exposure, but reducing that exposure via shorter treatment is associated with reduced risk of resistant infection and better clinical outcome, they say.

As the authors note, antibiotics are vital to modern medicine and resistance is a global, urgent threat to human health. But completing a course, they add, defies one of the most fundamental and widespread medication beliefs: that we should take as little medication as necessary.

Traditionally, antibiotics are prescribed for recommended durations or courses. Fundamental to the concept of an antibiotic course is the notion that shorter treatment will be inferior.

Concern that giving too little antibiotic treatment could select for resistance can be traced back to 1941, when Howard Florey’s team treated Albert Alexander’s staphylococcal sepsis with penicillin. They stretched out all the penicillin they had over four days by repeatedly recovering the drug from the patient’s urine. When the drug ran out, the clinical improvement they had noted reversed, and he subsequently succumbed to his infection. As the researchers note in their new study, there was no evidence that this was because of resistance, but the experience may have planted the idea that prolonged therapy was needed to avoid treatment failure.

More recently, in materials supporting Antibiotic Awareness Week 2016, the World Health Organization advised patients to “always complete the full prescription, even if you feel better, because stopping treatment early promotes the growth of drug-resistant bacteria.” Similar advice appears in national campaigns in Australia, Canada, the United States and throughout Europe. In the U.K., it’s included as fact in the curriculum for secondary school children, the authors note.

They also note there are exceptions for some types of antibiotics, including those used to treat tuberculosis.

They call for research to determine the most appropriate, simple alternative messages, such as stop when you feel better, and advise policy makers to publicly and actively state that the old message was not evidence-based and is incorrect. Clinical trials are required to determine the most effective strategies for optimizing duration of antibiotic treatment.

“The public,” they add, “should also be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved by tailoring treatment duration for individual patients.”

http://gizmodo.com/doctors-slam-new-recommendation-that-we-should-stop-ant-1797301481

Doctors Slam New Recommendation That We Should Stop Antibiotic Treatments Early

George Dvorsky

Today 1:15pmFiled to: ANTIBIOTICS

50

6

Image: Rob Brewer/Flickr

Scientists from the UK caused quite a stir this week, when they announced that we don’t necessarily need to complete a full course of antibiotics in order to treat infections properly. It’s a provocative message, but skeptics say their advice is grossly premature—and even reckless.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is not caused by putting an early stop to a prescribed course of antibiotics, but by antibiotic overuse, argue a team of infectious disease experts in The British Medical Journal. The team, led by Martin Llewelyn of the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, is asking doctors, educators, and policy makers to “stop advocating ‘complete the course’ when communicating with the public.”

Which, wow. This is a complete turn-around from what we’ve been told for years—that we need to finish our bottles right down to the last pill in order to properly treat our infections and prevent the proliferation of microbial resistant bacteria. According to these experts, we’ve been wrong about this, and what’s more, the “complete the course” culture may be responsible for the rapid decline in antibiotic effectiveness.

But the experts Gizmodo spoke to said the BMJ opinion piece, while important, may be sending the wrong message. They say a lot more research needs to be done before doctors can confidently start telling their patients to ease off their medications, and that the sweeping statement presented by the BMJ researchers fails to take the complex, multi-faceted nature of bacterial infections into account. In a word, they described the opinion piece as “dangerous.”

“The public should be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved.”

Llewelyn and his colleagues say the convention of prescribing long treatments is based on an outdated notion.

“Traditionally, antibiotics are prescribed for recommended durations or courses,” write the BMJ authors. “Fundamental to the concept of an antibiotic course is the notion that shorter treatment will be inferior. There is, however, little evidence that currently recommended durations are minimums, below which patients will be at increased risk of treatment failure.” Today’s prescription culture, they argue, is “driven by fear of undertreatment, with less concern about overuse.”

At the same time, the authors say there’s growing evidence that short course antibiotics—treatments lasting just three to five days—work just as effectively in treating an assortment of bacterial infections, and that we should move away from “blanket” prescriptions. But Llewelyn and his colleagues admit there are exceptions, citing the need to prescribe more than one type of antibiotic to TB infections, which are notorious for developing resistance.

The authors also admit it’s not going to be easy to change the culture, as the idea of taking a full course of antibiotics is “deeply embedded, and both doctors and patients currently regard failure to complete a course of antibiotics as “irresponsible behaviour.” But Llewelyn’s team is optimistic that the public will accept short-duration treatments if the medical profession openly acknowledges this shift in opinion, and that the public “be encouraged to recognize that antibiotics are a precious and finite natural resource that should be conserved.”

Skin bacteria. (Image: AP)

“I think the article is exciting, for so many practices in medicine it’s important to ask the origins and whether they are helping or harming patients,” said Harvard Medical School researcher Michael Baym, an expert in antibiotic resistance who wasn’t involved with the BMJ opinion piece. “The article establishes very well that the traditional seven-day course of antibiotic is not well founded, and that, consistent with evolutionary theory, a longer course does not lessen the emergence of resistance.”

That said, Baym says that replacing the general advice to finish a course with general advice to not finish a course is likewise based on insufficient evidence.

“I think the real conclusion is that we need to get away from the idea that all antibiotics and all infections require uniform thinking, and instead do specific studies to find out ideal treatment regimens for specific infections and specific antibiotics,” Baym told Gizmodo.

Maha R. Farhat, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Informatics at Harvard Medical School, agrees with Baym, saying the authors made an ambitious statement that isn’t currently founded in sufficient evidence.

“Most infectious disease doctors and antibiotic resistance specialists would like to see less use of antibiotics but the reality is that we we don’t yet have enough evidence to throw a blanket statement as the authors did,” Farhat told Gizmodo. “It’s true that collateral resistance is an issue, but what this should call for is more research and not a premature change in public health recommendations and awareness campaigns as the authors suggest.”

Farhat says the authors also failed to discuss evidence showing that antibiotic noncompliance—i.e. not necessarily shorter therapy, but interrupted therapy—is a key driver of resistance in both the patient and the larger population.

“Doctors, including myself, often emphasize the ‘take as prescribed’ statement because of a larger fear of the former [the patient]—which is more likely—than the latter [the larger population, or collateral resistance].”

Vaughn Cooper, a microbiologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, says we most certainly need to reconsider the the “one-size-fits-all” approach to antibiotic prescriptions, but he describes the new editorial as being “clearly dangerous.”

“Arguing that antibiotic course duration is not sufficiently evidence-based is worthwhile, but the editorial essentially argues that patients should not finish their course of antibiotics,” Cooper told Gizmodo. “This, too, is not evidence-based and increases the likelihood of adverse outcomes for patients disregarding medical advice when a course of antibiotics is clearly warranted.”

Article preview thumbnail

This Is Why You Shouldn’t Cut Your Kid’s Ear Infection Treatment Short

Some parents, wary of antibiotics, often cut their child’s ear infection treatments short. A new…

Read more

Cooper says the BMJ authors conveniently ignored what scientists already knew about antibiotics in terms of duration and efficacy, pointing to a New England Journal of Medicine study from last year showing that standard duration treatments—some lasting as long as ten days—do not increase a child’s level of antibiotic resistance (at least for kids with ear infections), and that children who are taken off antibiotics early exhibit worse outcomes.

“Suggesting patients not complete the recommended treatment course...is hazardous, for several reasons,” said Yonatan H. Grad, Assistant Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. “Not all infections are the same. For some infections, like TB, it is critically important to complete the treatment course, because, as has been demonstrated all too many times, not doing so promotes antimicrobial resistance in TB and recurrence of infection.”

Grad takes issue with the paper’s suggestion that patients stop taking antibiotics when they start to “feel better,” saying it’s too vague and subjective a recommendation. He also worries that a growing batch of unfinished bottles in the medicine cabinet will promote the inappropriate use of antibiotics, and have the exact opposite effect of what was intended.

“The critical problem of antimicrobial resistance should encourage us to revisit how we approach antibiotic use, as there are many opportunities for improvement,” Grad told Gizmodo. “As this opinion piece suggests, we need more clinical trials to determine the effectiveness of shorter duration treatments.”

Until that happens, you’d best finish your medications “as prescribed.”

[BMJ]

Recommended Stories

Antibiotic-Resistant Superbugs Could Kill 10 Million People a Year By 2050

Watch as Bacteria Evolve Antibiotic Resistance in a Gigantic Petri Dish

Electron microscope shows bacterial eating human: