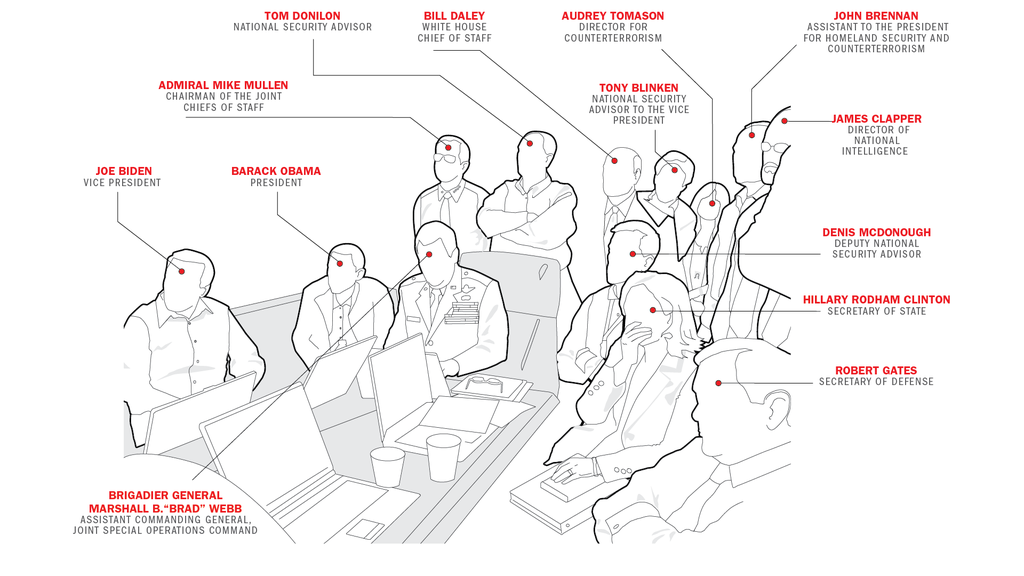

Michael Jordan

- Co Rentmeester

- 1984

It may be the most famous silhouette ever photographed. Shooting Michael Jordan for LIFE in 1984, Jacobus “Co” Rentmeester captured the basketball star soaring through the air for a dunk, legs split like a ballet dancer’s and left arm stretched to the stars. A beautiful image, but one unlikely to have endured had Nike not devised a logo for its young star that bore a striking resemblance to the photo. Seeking design inspiration for its first Air Jordan sneakers, Nike paid Rentmeester $150 for temporary use of his slides from the life shoot. Soon, “Jumpman” was etched onto shoes, clothing and bedroom walls around the world, eventually becoming one of the most popular commercial icons of all time. With Jumpman, Nike created the concept of athletes as valuable commercial properties unto themselves. The Air Jordan brand, which today features other superstar pitchmen, earned $3.2 billion in 2014. Rentmeester, meanwhile, has sued Nike for copyright infringement. No matter the outcome, it’s clear his image captures the ascendance of sports celebrity into a multibillion-dollar business, and it’s still taking off.