- Joined

- Jul 10, 2008

- Messages

- 66,782

- Points

- 113

How Does the Flu Actually Kill People?

Every year the common virus is lethal to many. What happens inside the body that results in death?

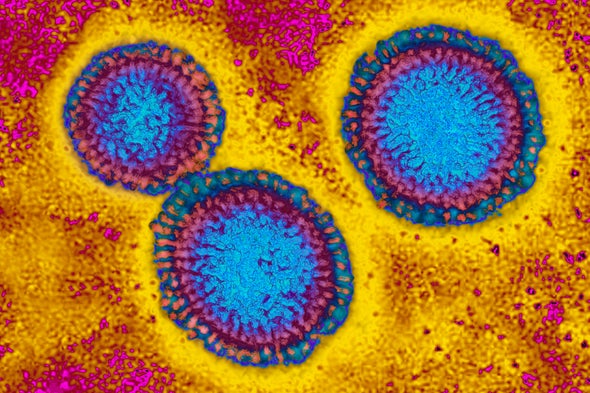

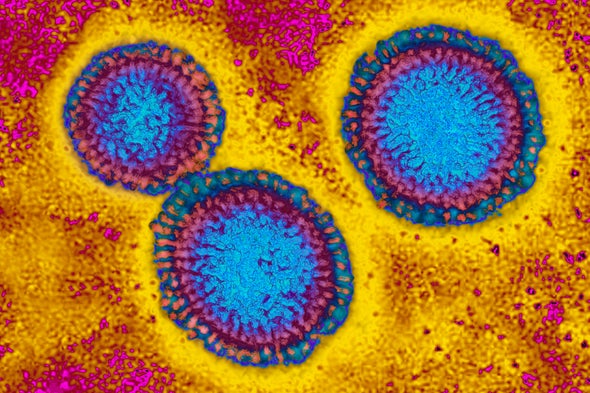

Influenza virus. Credit: BSIP Getty Images

One Sunday in November 20-year-old Alani Murrieta of Phoenix began to feel sick and left work early. She had no preexisting medical conditions but her health declined at a frighteningly rapid pace, as detailed by her family and friends in local media and on BuzzFeed News. The next day she went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with the flu and prescribed the antiviral medication Tamiflu. But by Tuesday morning she was having trouble breathing and was spitting up blood. Her family took her to the hospital, where x-rays revealed pneumonia: inflammation in the lungs that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection, or both. Doctors gave Murrieta intravenous antibiotics and were transferring her to the intensive care unit when her heart stopped; they resuscitated her but her heart stopped again. At 3:25 P.M. on Tuesday, November 28—one day after being diagnosed with the flu—Murrieta was declared dead.

FEATURED EBOOK

INDEPTH FLU COVERAGEA Deep Dive into the Science of Influenza5.99 View Details

Worldwide, the flu results in three million to five million cases of severe illness and 291,000 to 646,000 deaths annually, according to the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the totals vary greatly from one year to the next. The CDC estimates that between 1976 and 2005 the annual number of flu-related deaths in the U.S. ranged from a low of 3,000 to a high of 49,000. Between 2010 and 2016 yearly flu-related deaths in the U.S. ranged from 12,000 to 56,000.

But what exactly is a “flu-related death”? How does the flu kill? The short and morbid answer is that in most cases the body kills itself by trying to heal itself. “Dying from the flu is not like dying from a bullet or a black widow spider bite,” says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. “The presence of the virus itself isn't going to be what kills you. An infectious disease always has a complex interaction with its host.”

After entering someone's body—usually via the eyes, nose or mouth—the influenza virus begins hijacking human cells in the nose and throat to make copies of itself. The overwhelming viral hoard triggers a strong response from the immune system, which sends battalions of white blood cells, antibodies and inflammatory molecules to eliminate the threat. T cells attack and destroy tissue harboring the virus, particularly in the respiratory tract and lungs where the virus tends to take hold. In most healthy adults this process works, and they recover within days or weeks. But sometimes the immune system's reaction is too strong, destroying so much tissue in the lungs that they can no longer deliver enough oxygen to the blood, resulting in hypoxia and death.

In other cases it is not the flu virus itself that triggers an overwhelming and potentially fatal immune response but rather a secondary infection that takes advantage of a taxed immune system. Typically, bacteria—often a species of Streptococcus or Staphylococcus—infect the lungs. A bacterial infection in the respiratory tract can potentially spread to other parts of the body and the blood, even leading to septic shock: a life-threatening, body-wide, aggressive inflammatory response that damages multiple organs. Based on autopsy studies, Kathleen Sullivan, chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, estimates about one third of people who die from flu-related causes expire because the virus overwhelms the immune system; another third die from the immune response to secondary bacterial infections, usually in the lungs; and the remaining third perish due to the failure of one or more other organs.

Apart from a bacterial pneumonia, the secondary complications of the flu are numerous and range from the relatively mild, such as sinus and ear infections, to the much more severe, such as inflammation of the heart (myocarditis), brain (encephalitis) or muscles (myositis and rhabdomyolysis). They can also include Reye’s syndrome, a mysterious brain illness that usually begins after a viral infection, and Guillain–Barr syndrome, another virus-triggered ailment in which the immune system attacks the peripheral nervous system. Sometimes Guillain–Barr leads to a period of partial or near-total paralysis, which in turn requires mechanical ventilation to keep a sufferer breathing. These complications are less common, but can be fatal.

The number of people who die from an immune response to the initial viral infection versus a secondary bacterial infection depends, in part, on the viral strain and the cleanliness of the spaces in which the sick are housed. Some studies suggest that during the infamous 1918 global flu pandemic, most people died from subsequent bacterial infections. But more virulent strains such as those that cause avian flu are more likely to overwhelm the immune system on their own. “The hypothesis is that virulent strains trigger a stronger inflammatory response,” Adalja says. “It also depends on the age group getting attacked. During the H1N1 2009 pandemic, the age group mostly affected was young adults, and we saw a lot of primary viral pneumonia.”

In a typical season most flu-related deaths occur among children and the elderly, both of whom are uniquely vulnerable. The immune system is an adaptive network of organs that learns how best to recognize and respond to threats over time. Because the immune systems of children are relatively naive, they may not respond optimally. In contrast the immune systems of the elderly are often weakened by a combination of age and underlying illness. Both the very young and very old may also be less able to tolerate and recover from the immune system's self-attack. Apart from children between six and 59 months and individuals older than 65 years, those at the greatest risk of developing potentially fatal complications are pregnant women, health care workers and people with certain chronic medical conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, asthma, and heart or lung diseases, according to the World Health Organization.

Every year the common virus is lethal to many. What happens inside the body that results in death?

- By Ferris Jabr on December 18, 2017

Influenza virus. Credit: BSIP Getty Images

One Sunday in November 20-year-old Alani Murrieta of Phoenix began to feel sick and left work early. She had no preexisting medical conditions but her health declined at a frighteningly rapid pace, as detailed by her family and friends in local media and on BuzzFeed News. The next day she went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with the flu and prescribed the antiviral medication Tamiflu. But by Tuesday morning she was having trouble breathing and was spitting up blood. Her family took her to the hospital, where x-rays revealed pneumonia: inflammation in the lungs that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection, or both. Doctors gave Murrieta intravenous antibiotics and were transferring her to the intensive care unit when her heart stopped; they resuscitated her but her heart stopped again. At 3:25 P.M. on Tuesday, November 28—one day after being diagnosed with the flu—Murrieta was declared dead.

FEATURED EBOOK

INDEPTH FLU COVERAGEA Deep Dive into the Science of Influenza5.99 View Details

Worldwide, the flu results in three million to five million cases of severe illness and 291,000 to 646,000 deaths annually, according to the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the totals vary greatly from one year to the next. The CDC estimates that between 1976 and 2005 the annual number of flu-related deaths in the U.S. ranged from a low of 3,000 to a high of 49,000. Between 2010 and 2016 yearly flu-related deaths in the U.S. ranged from 12,000 to 56,000.

But what exactly is a “flu-related death”? How does the flu kill? The short and morbid answer is that in most cases the body kills itself by trying to heal itself. “Dying from the flu is not like dying from a bullet or a black widow spider bite,” says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. “The presence of the virus itself isn't going to be what kills you. An infectious disease always has a complex interaction with its host.”

After entering someone's body—usually via the eyes, nose or mouth—the influenza virus begins hijacking human cells in the nose and throat to make copies of itself. The overwhelming viral hoard triggers a strong response from the immune system, which sends battalions of white blood cells, antibodies and inflammatory molecules to eliminate the threat. T cells attack and destroy tissue harboring the virus, particularly in the respiratory tract and lungs where the virus tends to take hold. In most healthy adults this process works, and they recover within days or weeks. But sometimes the immune system's reaction is too strong, destroying so much tissue in the lungs that they can no longer deliver enough oxygen to the blood, resulting in hypoxia and death.

In other cases it is not the flu virus itself that triggers an overwhelming and potentially fatal immune response but rather a secondary infection that takes advantage of a taxed immune system. Typically, bacteria—often a species of Streptococcus or Staphylococcus—infect the lungs. A bacterial infection in the respiratory tract can potentially spread to other parts of the body and the blood, even leading to septic shock: a life-threatening, body-wide, aggressive inflammatory response that damages multiple organs. Based on autopsy studies, Kathleen Sullivan, chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, estimates about one third of people who die from flu-related causes expire because the virus overwhelms the immune system; another third die from the immune response to secondary bacterial infections, usually in the lungs; and the remaining third perish due to the failure of one or more other organs.

Apart from a bacterial pneumonia, the secondary complications of the flu are numerous and range from the relatively mild, such as sinus and ear infections, to the much more severe, such as inflammation of the heart (myocarditis), brain (encephalitis) or muscles (myositis and rhabdomyolysis). They can also include Reye’s syndrome, a mysterious brain illness that usually begins after a viral infection, and Guillain–Barr syndrome, another virus-triggered ailment in which the immune system attacks the peripheral nervous system. Sometimes Guillain–Barr leads to a period of partial or near-total paralysis, which in turn requires mechanical ventilation to keep a sufferer breathing. These complications are less common, but can be fatal.

The number of people who die from an immune response to the initial viral infection versus a secondary bacterial infection depends, in part, on the viral strain and the cleanliness of the spaces in which the sick are housed. Some studies suggest that during the infamous 1918 global flu pandemic, most people died from subsequent bacterial infections. But more virulent strains such as those that cause avian flu are more likely to overwhelm the immune system on their own. “The hypothesis is that virulent strains trigger a stronger inflammatory response,” Adalja says. “It also depends on the age group getting attacked. During the H1N1 2009 pandemic, the age group mostly affected was young adults, and we saw a lot of primary viral pneumonia.”

In a typical season most flu-related deaths occur among children and the elderly, both of whom are uniquely vulnerable. The immune system is an adaptive network of organs that learns how best to recognize and respond to threats over time. Because the immune systems of children are relatively naive, they may not respond optimally. In contrast the immune systems of the elderly are often weakened by a combination of age and underlying illness. Both the very young and very old may also be less able to tolerate and recover from the immune system's self-attack. Apart from children between six and 59 months and individuals older than 65 years, those at the greatest risk of developing potentially fatal complications are pregnant women, health care workers and people with certain chronic medical conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, asthma, and heart or lung diseases, according to the World Health Organization.

. I hope more people would know this and just calm the fuck down.

. I hope more people would know this and just calm the fuck down.