Thoroughly enjoyed reading this heart warming editorial and decided to share it with the bros here. Soul-less 154th journalists will never come up with this kind of quality writing

Capturing the moment: what happened to the boys in this picture?

When the photographer Peter Widing, a close friend of mine, died last year I decided to do something the two of us had often talked about: finding the three young players from a picture I had loved since I first saw it 11 years ago

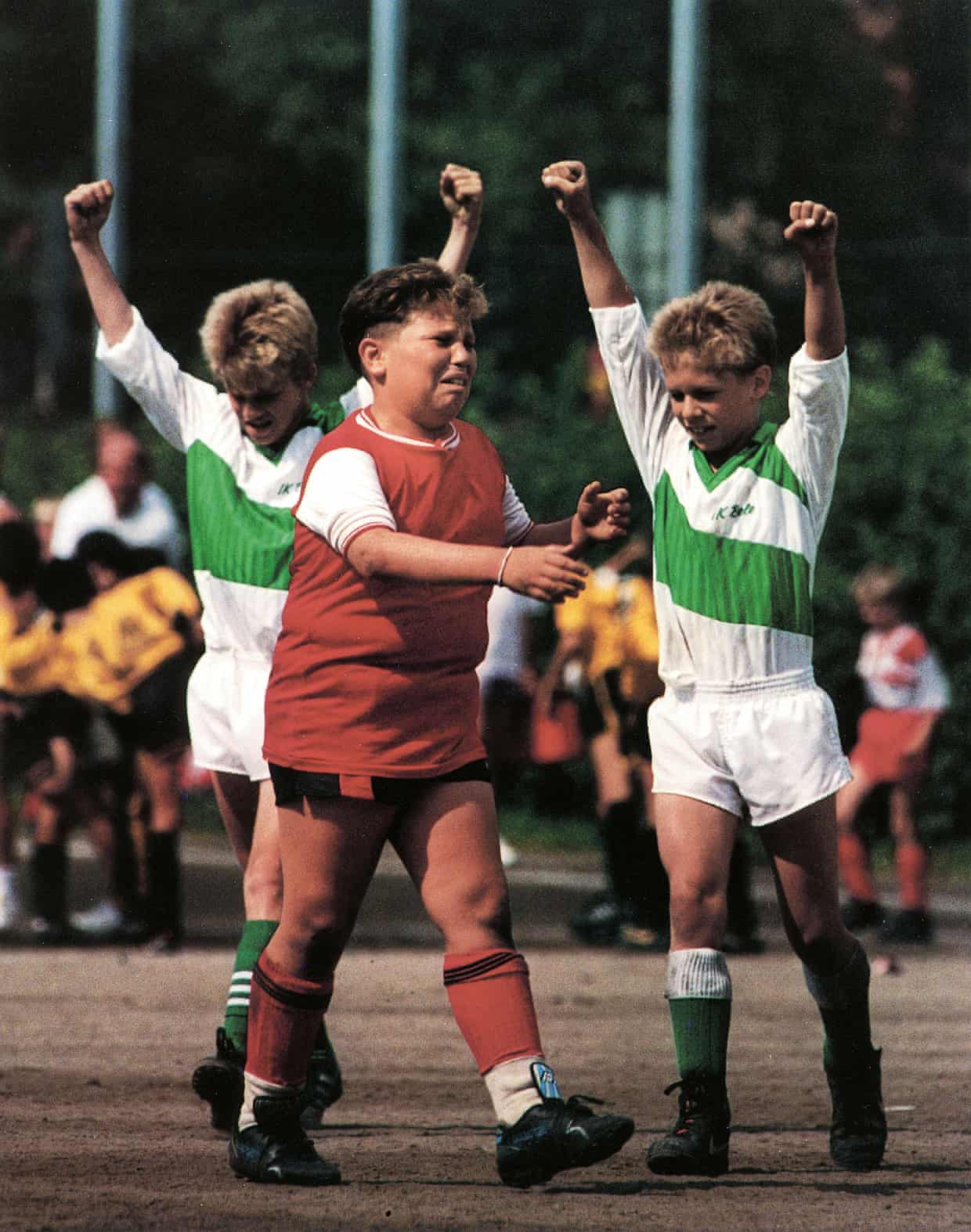

Heaven and hell: a picture from the Gothia Cup youth football tournament in 1990. Nine-hundred-and-thirty-seven teams from 42 different countries took part that year. Photograph: Peter Widing

Anders Bengtsson

Monday 13 November 2017 10.00 GMT

Last modified on Monday 13 November 2017 22.00 GMT

It was July 1990, and a week which started with an earthquake in the Philippines that killed 1,621 people and ended with Roger Waters performing The Wall in front of almost 500,000 people in Berlin. The businessman Donald Trump was only a few minutes away from going bankrupt.

The weather was sunny in Sweden between 15 and 21 July, pleasing all those in the middle of their holidays. The photographer Peter Widing, however, was not on holiday. He was working.

The 22-year-old was covering a youth football tournament, the Gothia Cup, for the Expressen newspaper. By one of the pitches he stopped and raised his camera. Maybe he already felt he had captured something special, but it was not until he developed the film that he saw the result.

The first time I saw what Widing had captured was 16 years later. I was doing work experience at the Offside football magazine and on the walls there were nine blown-up, framed photographs. All of them were taken by Widing. One was from a full Maracanã, another of Peter Schmeichel picking the ball out of the net during Euro 92. But the one I couldn’t take my eyes off was the picture Peter took that July day in 1990. Two blond, almost twin-like boys celebrating a goal or win. The shirts are neatly tucked into their shorts. In front of them, a chubby, sad opponent whose dreams had just been crushed.

The picture would not have had the same devastating effect had it been taken a second earlier or later. It is a moment that requires the blond boys’ synchronised celebrations, which, in turn, would not have meant anything if it was not for the contrasting boy in tears and tight shirt. It is a work of art that I have loved for the past 11 years.

When I had worked at Offside for a while and was given my own room I took the picture with me and hung it on the wall above my desk. I have looked at the boys so many times and wondered how their lives turned out. Sometimes I said to Peter that we should track them down. But he mainly shrugged and said it would never work. He was a man of few words and coming from him it meant something more like: “I will happily help if we really decide that we are going to do it.”

We never did. On 29 May 2016 Peter killed himself. His death was unimaginable and affected me more than anything else I have experienced. He was not only a colleague for 10 years but also a special friend. It is said that time heals every wound and perhaps the sorrow has diminished but I do not want to forget him and the picture has an important part to play. It still hangs above my desk and every time I look at the three boys I think of Peter.

Peter Widing worked for the Swedish daily Expressen before joining Offside. ‘He saw things I did not see myself,’ one former colleague, Mats Olsson, said.

Last winter I decided to find the main characters. There were a few clues in the picture. The boys looked like they were between 11 and 13 years old, which meant they should have been between 38 and 40 when I started looking. And because the picture is taken just as the boy to the right lifts his arms a club badge is revealed: Bele IK

Google says Bele is a club from Järfälla, outside Stockholm. In 2001 they merged with Barkaby SK to become Bele Barkaby IF. I email a club director and as I wait for a reply I contact the club which has organised the Gothia Cup since 1975, BK Häcken. They have no documentation from the 1990 tournament. “Sadly nothing.”

I visit a library in Gothenburg which has a microfiche of newspapers going back to the second world war. I look at Expressen between 15-21 July in 1990 – but there is no picture from Heden, where the tournament took place. Another local, newspaper, Göteborgs Posten, wrote more about the tournament but there is not a single mention of Bele IK. Disappointed, I leave the library and realise that even if someone working at Bele Barkaby can help me, they will find it difficult to remember a game from a tournament 27 years ago.

The only thing I know is that 937 teams from 42 different countries took part. One player, from a team called Voluntas, was called Andrea Pirlo. He was 11 that summer.

I cannot rule out that one of the three boys may have died, or is now a convicted murderer, or could have played 200 games in the Swedish top flight, that I might even have interviewed one of them.

Suddenly I got a text from Håkan, who works with Bele Barkaby: “I’ve got the names now. Will email you tomorrow, the boys love the photo!”

I ask excitedly if the boys had any details. “One of the lads thought they played a team from Malta.”

I phone Markus Gellner, the blond boy on the right of the picture, the next day. “Nah,” he says. “I think we were playing a team from Germany. I think we won big and maybe that’s why the boy is crying.”

He tells me he was born in 1978, which means that it was an under-12 game that was being played in July 1990. His team-mate in the picture is Mattias Dixner and they were best friends from Year 1 to the end of primary school; they played together almost every day. “I also remember playing a team from Germany,” Mattias says on the phone. “But also a team from Malta.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest

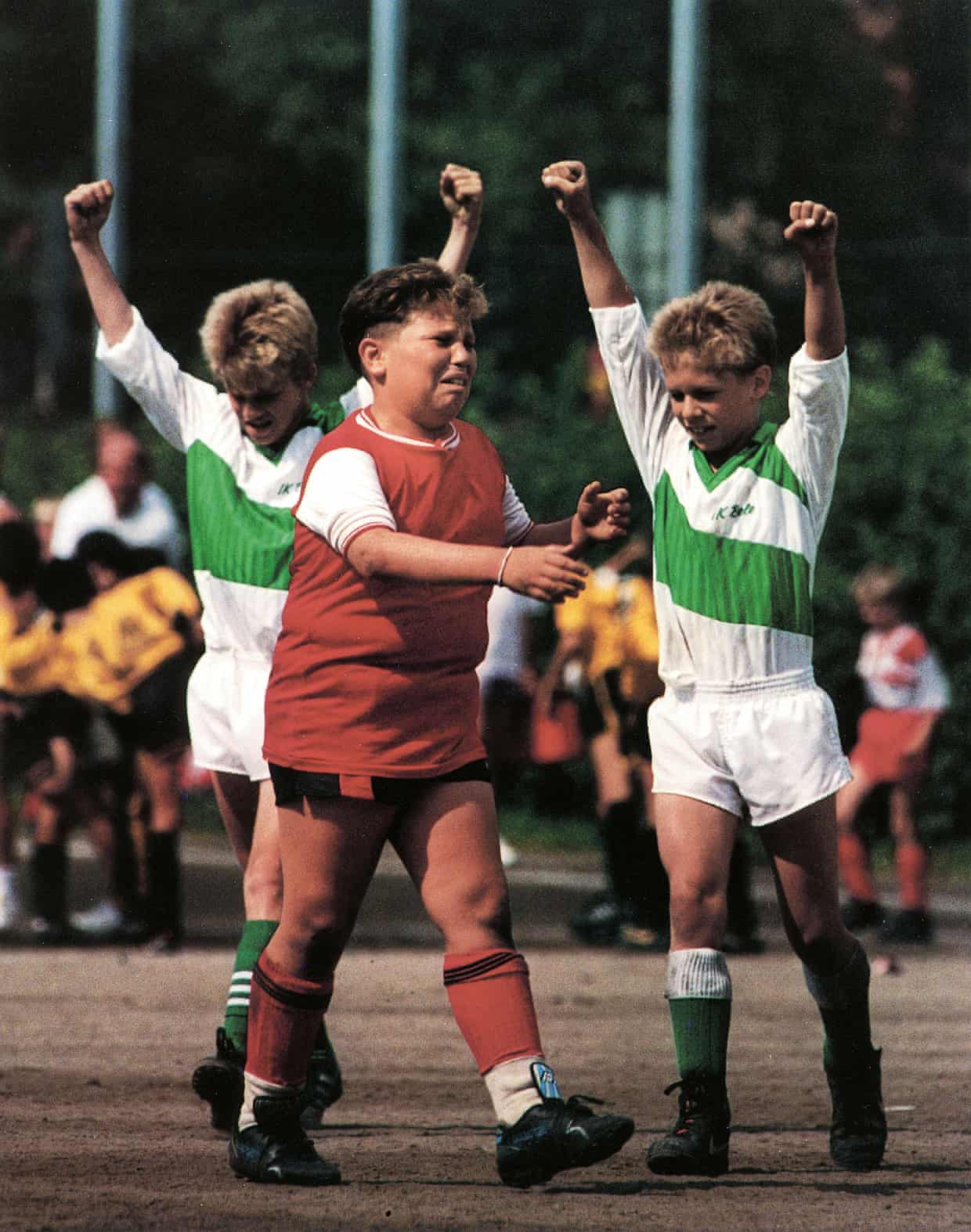

Mattias Dixner, left, the boy to the left in the picture at the top, mainly played football because his friends did and now prefers Formula One. Markus Gellner, the boy to the right in the top picture, joined top-flight side AIK but suffered a serious injury and started to spend more time in the gym. Photographs by Daniel Nilsson

I meet Mattias in a restaurant in Stockholm later, and he says: “I played football because all my friends did it. We had fun together and I didn’t want to be left out of that. Markus, on the other hand, lived for football. We lived about 500 metres from each other and there was a football pitch between us. So we just used to hang out there.”

Markus and Mattias drifted apart. Today Mattias is married and has two children. His interest in football is minimal. He played a season for Lökringen Oilers at a very low level but if he has some spare time he would rather watch Formula One.

When I meet Markus I ask whether he remembers anything specific, something that can lead me to the third boy.

He puts some snus underneath his upper lip and says: “I really think it was a team from Malta … but I don’t know why. We reached the B play-off but I think that picture is from the group stage. I remember we beat a German team 13-0 because we were going around singing “drei-zehn – null!” Beating a German team was big.”

Markus later joined the top-flight club AIK and was making good progress when, at break time at school, he was playing football and something in the back of his thigh went. The X-ray showed that a bit of bone had avulsed from his pelvis. He was told it was “impossible” to operate and that all he could do was wait. Six months soon became a year. No football. “The rehab took three years,” Markus says. “Slowly I lost contact with football without really noticing. Maybe it was lucky that it happened then, at a time in life when so much else is happening. New friends, girls, parties …”

Markus spent more and more time in the gym and finished second in a Swedish event called “athletic fitness” in 2005. “But then I reached a point where I started to question myself: ‘What am I doing?’ I had been obsessed with training for several years. One summer’s day I finished a training session and was walking to my apartment. People had their barbecues out and were drinking beers. There I was in heavy clothing so I would sweat as much as possible. It was a wake-up call. I had met my future wife Matilda and realised there was more to life than training so I stopped. I still train but it is at a reasonable level now. I like to drink a few beers, if we can put it that way.”

Markus wishes me good luck in finding the third person but there seems to be no information on who Bele IK were playing that day.

The weeks pass and I start to think I have reached the end of the road. But that’s not how it can end. Peter was the most stubborn person I ever met. He would not have given up.

I send a desperate email to BK Häcken, the organisers of the Gothia Cup, and include as many people as possible whose email addresses I can find on the club website. I tell them about Markus and Mattias and that it could be a team from either Malta or Germany. “Is there someone who is connected to the Gothia Cup with an extremely good memory?” I ask.

A few hours later I got a reply from Dennis Andersson, the club chairman. “During this period we had a lot of teams from Malta. The teams had different names but almost all the time they had the same sporting leader, Edgar Tonna. If the boy is from Malta then there is a good chance that Edgar can find him.”

I email Edgar but there is no reply. I look him up online and it seems as if he is alive and coaching youth teams in Malta. But no phone numbers, no Facebook. Then, after a week, he replies: “I have read your email and the player in the picture is Kevin Fenech. He played for Naxxar Lions and was dubbed ‘the Maltese Paul Gascoigne’ in one Swedish newspaper because of his dribbling skills. I’ll be in touch again.”

Kevin Fenech, the boy in the middle of the top picture, was described as ‘the Maltese Paul Gascoigne’ by one Swedish paper. Photograph: Anders Bengtsson

He later phones and gives me a number for Kevin. I dial the number the day after. Three times it rings before I hear a voice.

“Hello?”

“Hi, is this Kevin Fenech?”

“Yes.”

Two days later I am on a plane to Malta.

I first meet Edgar, Kevin’s coach in 1990. He told me Kevin was Naxxar’s best player and scored “four or five goals” in the tournament. Edgar says that it was such a huge experience for the boys to travel to Gothenburg. For many of them it was the first time they had been outside Malta. He tells me that one of the boys met a girl from China. The two of them became pen pals and 10 years later the Chinese girl moved to Malta. They are still together as far as Edgar knows.

There are sad stories as well. Edgar tells me their goalkeeper at the Gothia Cup, Simon, discovered a month after the tournament that he had leukemia and died soon afterwards. “The whole team was at the funeral,” says Edgar. “It was unbearably sad. Most of that team was in the same class and knew each other extremely well. Before he died he said he wanted to get buried in his goalkeeping jersey. So there he was in the coffin with the same shirt he had worn at the Gothia Cup. It was terrible.”

In Valletta the sky is blue and it is 21C as I wait for Kevin. At long last I am going to meet the boy with the tear-filled cheeks who has escaped me for so many years. We hug each other when he arrives. He is short, newly shaved and in good spirits. He is nothing like the chubby boy I have looked at so many times down the years. The 39-year-old Kevin Fenech is in good shape.

I show him the picture. “Wow, I wasn’t just a little chubby. I was fat! I guess I was [fat] for a few years. You know, I loved sweets and ice cream.”

Kevin stopped playing football two years after the tournament in Sweden and it was not until he was 17 that he picked it up again. He realised how much he missed it: the togetherness and the friends. When he was appointed as an administrator in the army he started playing for their team and then rejoined Naxxar Lions, whose first team were soaring through the divisions.

“I’ve kept that newspaper article about me and Gascoigne. It is funny because Gazza really was my idol. I was a bit round like him and I said to my mum to cut my hair like him.”

He looks out over the sea and continues: “Yes, I cried a lot. My mood was terrible and I cried after every game we lost. But this time it was because we had just conceded. Because we actually won against Bele, 3-1. We won our group and didn’t lose a game before we went out against that other Swedish team … Ytterby? You should have seen me then. I think I cried for two hours after that game. An old Swedish man felt so sorry for me that he bought me a large ice cream.”

Before we finish, he says: “It was a really talented photographer in any case. He really captured me.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest

Peter Widing’s picture in full.

As the sun sets on my last evening on the Mediterranean I sit in an Italian restaurant and think about Kevin, Markus and Mattias. Life has worked out well for them. They are parents and all seem to be good dads.

Kevin said he was a bit fed up with his work in the army but then corrected himself. “A lot of the army’s time is spent on all the people who flee from north Africa. They come in a dinghy in worn-out clothes without a single possession. When I complain my wife says to me ‘It’s not you we should feel sorry for, Kevin.’

How Kevin’s, Markus’s and Mattias’s lives will turn out nobody knows. Peter is proof of that. So I think about how Peter would have loved the sun in Malta, that he would have liked the restaurant. Italian food was his favourite. I order a bottle of Amarone, the wine Peter preferred and raise my glass to my lips, pausing before I take a first sip. Quietly I say: “It worked out, Widdy. We did it, buddy.”

This is a translated and edited extract from a piece which initially appeared in the Swedish football magazine Offside in June 2017.