https://mil.news.sina.com.cn/china/2019-07-09/doc-ihytcerm2283734.shtml

英媒:中英实力悬殊 中国理所应当鄙视英国

2019年07月09日 07:25 环球时报

7,814

原标题:英媒:中国理所应当鄙视英国。

本文译自英国《卫报》7月6日文章,原题:中国看英国,只看到虚弱和虚伪

香港暴力事件引发英国与中国爆发口水战。令人不安的是,此事也凸显在一个强敌如林的世界里,未来脱欧后的英国显得孤立无援、虚弱无力。它还暴露所有西方民主国家与北京打交道时的一个难题:什么才是最重要的——自由价值还是赚钱发财?

中国驻英大使要求英国“勿插手香港事务”,把外交大臣亨特公开支持抗议者解读为支持暴力。另一名中方官员指责亨特“似乎还沉浸在昔日英国殖民者的幻象当中”。中方表示,英国暗中煽动骚乱是制造动荡的更大阴谋的一部分。与此同时,英国被嘲笑为一个虚弱、失败的国家,连自己国内问题都管不好。

中国对英国这种根深蒂固的愤怒,源自在伦敦基本被忘记、而在北京却没忘记的过去。正如中方所言,战后殖民主义国家英国对香港居民的权利毫无尊重可言。这种漠视与早先维多利亚时代的帝国主义者对清王朝所施加的屈辱——也是中国“失落的世纪”的起因——是一脉相承的。

亨特抨击北京背弃《中英联合声明》,称中国冒犯了自己从中获益的基于规则的国际秩序。然而,如此“义正辞严”的话语出自一个没有合法授权就在伊拉克进行战争的国家,不免显得尴尬。它还忽视了19世纪欧洲列强对华“不平等条约”那段无法无天的历史。昔日的不平等影响了中国20世纪反帝国主义的民族主义意识形态——以及收复对“失去”领土的主权的坚持。

对于英国的警告,中国不屑甚至近乎蔑视。这不仅是基于伦敦过去的虚伪和历史健忘症,而且是中国对于英国目前明显弱势的敏锐评估。鉴于中英两国实力悬殊,亨特的“将会有严重后果”之威胁几乎毫无意义。

现实是惨痛的。英国脱欧后需要贸易协议,需要中国的投资、中国的技术甚至华为(如果美国能允许的话)。而中国并不真正需要英国。英国相对依赖中国,单独采取行动,根本改变不了中方的行为或有效促进自身价值。这需要某种只有强大同盟才能带来的筹码。由于特朗普不可信任,这就意味着需要欧洲统一战线。但如今,欧洲被(英国)鲁莽地晾在一边。亨特说英国仍是一个具有“全球影响力”的国家,但其所作所为却在削弱英国的国际领导地位和影响力。中国理所应当鄙视英国。

British media: China and Britain's strength gap China should despise Britain

July 09, 2019 07:25 Global Times

7,814

Original title: British media: China should despise Britain.

This article is translated from the British "Guardian" July 6 article, the original title: China to see the UK, only see weakness and hypocrisy

The violence in Hong Kong triggered a war of words between Britain and China. What is disturbing is that this matter is also highlighted in a world of strong enemies such as Lin. After the Brexit, the United Kingdom seems to be helpless and weak. It also reveals a problem when all Western democracies deal with Beijing: What is the most important – free value or money to make money?

The Chinese ambassador to the United Kingdom asked the United Kingdom to "do not intervene in Hong Kong affairs" and to interpret the protesters as support for violence by Foreign Minister Hunter. Another Chinese official accused Hunter of "seemingly still immersed in the illusion of the former British colonists." The Chinese side said that the British secretly inciting riots is part of a larger conspiracy to create turmoil. At the same time, Britain was ridiculed as a weak, failed country, and even its own domestic problems were not well managed.

China’s deep-rooted anger against Britain stems from the past that was largely forgotten in London but not forgotten in Beijing. As the Chinese have said, the post-war colonialist country has no respect for the rights of Hong Kong residents. This indifference and the humiliation exerted by the earlier Victorian imperialists on the Qing Dynasty, which is also the cause of China's "lost century", is in the same vein.

Hunter slammed Beijing for abandoning the Sino-British Joint Declaration, saying that China offended the rule-based international order that it benefited from. However, such a "righteousness and resignation" discourse comes from a country that has not legally authorized to wage war in Iraq. It also ignores the lawless history of the “unequal treaties” of European powers in China in the 19th century. The inequality of the past has affected China’s anti-imperialist nationalist ideology in the 20th century – and the reinstatement of its sovereignty over “lost” territories.

For the British warning, China disdains and even scorns. This is not only based on London's past hypocrisy and historical amnesia, but also a keen assessment of China's current apparent weakness. Given the disparity in power between China and the UK, Hunter’s threat of “will have serious consequences” is almost meaningless.

The reality is bitter. The UK needs a trade agreement after Brexit and needs Chinese investment, Chinese technology and even Huawei (if the US can allow it). And China does not really need the UK. The United Kingdom is relatively dependent on China and acts alone. It cannot fundamentally change the behavior of China or effectively promote its own value. This requires some kind of chip that only a strong alliance can bring. Since Trump is untrustworthy, this means the need for a European united front. But now, Europe is being ruined by the (UK). Hunt said that Britain is still a country with "global influence", but its actions are weakening Britain's international leadership and influence. China should despise Britain.

https://www.theguardian.com/comment...ng-kong-jeremy-hunt-britain-rules-waves-wrong

Someone, please tell Jeremy Hunt: Britain no longer rules the waves

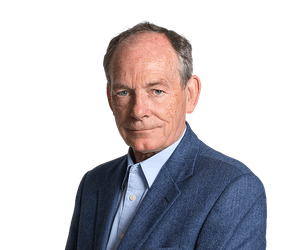

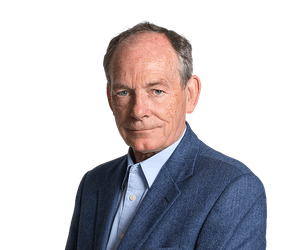

Simon Jenkins

He prefers to inflate his Tory leadership chances than face the truth about Britain’s lack of influence in Hong Kong

Thu 4 Jul 2019 17.07 BST Last modified on Fri 5 Jul 2019 09.52 BST

Shares

574

Comments

560

‘Britain left with a certain dignity’: the royal yacht Britannia sails into Hong Kong harbour on 23 June 1997. Photograph: Anthony Wallace/AFP/Getty Images

It was June 1997 and I was standing in the crowd on Hong Kong’s waterfront in torrential rain. A sad bugle played as the flag was lowered, and the royal yacht Britannia carried the Prince of Wales out to sea – and Britain out of its last Asian colony. We all had one thought. Thank goodness that’s over. Hong Kong’s last governor, Chris Patten, left what China clearly saw as a mess on the carpet, an elected assembly under the slogan “one country, two systems”. No one expected it to last, but Britain left with a certain dignity.

So why did Britain’s foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, take it on himself this week to revisit the scene? He applauded Hong Kong’s recent demonstrations and warned Beijing not to crack down on the rioters. He said the Chinese regime should not use a few broken windows as “a pretext for repression”. Britain would not stand for it. He said there would be “serious consequences”.

As was glaringly obvious, Hunt’s remarks had nothing to do with Hong Kong. He was puffing up his chest and signalling virtue in his contest for Downing Street with Boris Johnson. He wanted to show himself a player who could talk big on the world stage, who could move mountains. Johnson, he implied, could only move a few London cycle lanes.

China’s ambassador in London, Liu Xiaoming, might well have let this childishness pass, but he could not resist a crushing rejoinder. He said the issue was not the freedom of Hong Kong’s citizens to protest, which has been much tolerated over recent weeks. The issue was violence and vandalism against a democratic assembly. That was a crime. London should understand that, under Britain’s much-vaunted legacy, Hong Kong’s elected government and judiciary were responsible for crime, not Beijing.

Facebook Twitter

Pinterest

Jeremy Hunt: ‘He was puffing up his chest and signalling virtue in his contest for Downing Street.’ Photograph: Pool/Reuters

Liu pointed out that Hong Kong had enjoyed more democratic self-government under the shadow of Beijing than it had in a century and a half of British rule. Under Britain “there was no freedom, no democracy whatever” nor the right “to have an independent judicial power”. Hunt’s “gross and unacceptable” remarks offended the guiding principles of “mutual respect and non-interference in internal affairs”, long espoused by both countries. A spokesman in Beijing went further. Britain was hypocritical. He implied that it should sort out Brexit and leave Hong Kong to mend its own windows. The Foreign Office summoned the ambassador and told him not to be so rude – or once again there would be “serious consequences”.

The 1984 and 1994 bilateral accords on Hong Kong’s future were diplomatic triumphs of post-colonial history. Compromises were reached between diametrically opposed positions. China conceded the colony half a century of democracy to 2047, largely in return for a quiet life and a useful business outlet. As a result, a partial autonomy survived in the territory even during periods of repression elsewhere in China.

Anyone who now visits Hong Kong is aware of the fragility of this settlement. The presence on Chinese soil of a measure of alien democracy and human rights hangs by a thread. Recent street protests against the brutal extradition law were impressive and, so far, successful. The weekend’s descent into violence was trivial but, to a hypersensitive Beijing, alarming. The demonstrators provocative unfurling of the old British flag played into the hands of the Chinese hard-liners.

1:40

How Hong Kong protesters used hand signals and human chains to storm government – video explainer

The reality has always been that the 1984 deal depended on Beijing sticking to it; and that in turn will depend on how far the activists in Hong Kong push their luck. Beijing has already toppled three Hong Kong chief executives, and dares not lose effective control. The one certainty is that what happens between now and 2047 will be the outcome of a resolution of forces within China’s shifting elites, and nowhere else.

It is therefore hard to imagine a more blundering, cliched and counterproductive intervention than Hunt’s. The idea that Beijing would shift its policy one inch because someone halfway round the world was frantic to advance his career is farcical. As for Britain offering any practical aid or comfort to the street protesters, that is preposterous if not a cruel deception. What does Hunt mean by serious consequences? Will he send an aircraft carrier?

Jeremy Hunt refuses to rule out sanctions against China

Read more

The ritual of British ministers “raising human rights issues” with Beijing has long been a charade. The post-2008, pre-2012 Olympics talks – with London begging advice while criticising human rights abuses – was embarrassing to all concerned. The same went for David Cameron and George Osborne’s bizarre “kowtow diplomacy” in 2015, seeking funds for such vanity projects as Hinkley Point, HS2 and the “northern powerhouse”. It just gave China leverage over chunks of British infrastructure.

Hunt is currently championing hard Brexit on the basis that vast riches lie in bilateral deals “with the rest of the world”. If so, is he really going to embargo Chinese trade as a consequence of Hong Kong? He should watch out that Beijing does not return the compliment.

As Hunt walks to his Foreign Office chamber, he passes majestic paintings and sculptures celebrating the wonders that British imperial rule brought to the four corners of the Earth. It is tempting for his head to be turned by the voluptuous symbols of British power projection. It has clearly happened. Damn it, say the pictures, we used to rule the world.

Like Tony Blair, Hunt aches to blunder about the world declaring all its evils “unacceptable” and arguing “something must be done” about them. He wants his office to “punch above its weight”. Hong Kong is not his country and not his business. Britain handed it back to China two decades ago, surrendering sovereignty over it to an immeasurably greater power. Yet for people like Hunt it seems the imperial urge will never ease.

• Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/06/china-britain-weakness-hypocrisy-jeremy-hunt-hong-kong

China looks at Britain and sees only weakness and hypocrisy

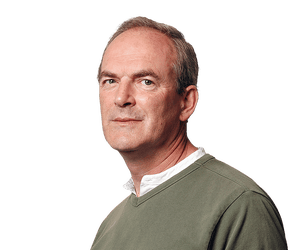

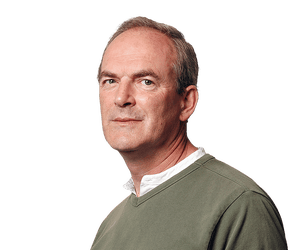

Simon Tisdall

Jeremy Hunt’s support for the Hong Kong protests has released old resentments long suppressed

Sat 6 Jul 2019 14.00 BST Last modified on Sat 6 Jul 2019 23.00 BST

Shares

1,181

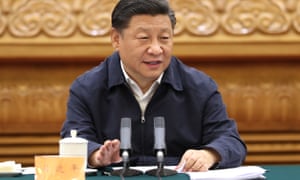

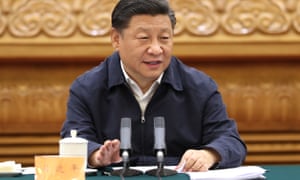

President Xi Jinping at a meeting in Beijing. Photograph: Huang Jingwen/Xinhua/Barcroft Media

Last week’s sudden outbreak of verbal hostilities with China, triggered by violent clashes in Hong Kong, provided a disturbing glimpse of post-Brexit Britain’s isolated and impotent future in a world of more muscular adversaries. It also underlined a dilemma facing all the western democracies in their dealings with Beijing: what matters most – liberal values or money-making?

Like bullies sensing weakness, Chinese officials let rip after Britain dared defend the demonstrators’ right to protest against the erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms. The row released tensions largely suppressed since the former colony was handed back in 1997. The depth of China’s pent-up fury was cautionary.

Liu Xiaoming, China’s ambassador, led the charge, demanding Britain keep its “hands off Hong Kong”. Liu misrepresented the foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt’s public support for the protesters as implying support for violence. Another official was personally insulting, accusing Hunt of “basking in the faded glory of British colonialism”.

Guardian Today: the headlines, the analysis, the debate - sent direct to you

Read more

China’s claim that Britain was surreptitiously fomenting unrest as part of a wider destabilisation conspiracy was classic Communist party propaganda-cum-paranoia. At the same time, Britain was mocked as an enfeebled, failing country, unable to manage its own internal problems. The obvious contradiction did not inhibit the rhetoric.

These broadsides, intended to demonstrate proud resilience, spoke instead of abiding insecurity. Xi Jinping, China’s “strongman” leader and de facto president-for-life, is said to have been deeply influenced by the east European revolutions of 1989 and the subsequent implosion of the Soviet Union.

Xi fears one-party China could go the same way. “Why did the Soviet Communist party collapse?” Xi asked in 2013 when discussing the risks posed by popular insurrections. One reason, he said, was that “nobody was a real man”. That tough-guy Xi is determined not to repeat Mikhail Gorbachev’s supposed mistakes is already abundantly clear.

His time in power since 2012 has been marked by expanding state control, a Mao-style personality cult reinforced by purges of party rivals (dressed up as anti-corruption drives), mass detentions and human rights abuses, pervasive censorship and an aggressive foreign policy signalling China’s ambitions as a global superpower.

Hong Kong’s demand for democratic self-determination directly contradicts Xi’s vision of the unchallengeable power of the party and its “core leader”. It threatens his ascendancy. Worse, it could encourage copycat resistance in mainland China, where public discontent exacerbated by an economic slowdown is growing.

That means more Hong Kong arrests and jailings. It means a slow-motion stifling of dissent, whatever Britain may say. And despite Thursday’s limited offer of talks, it may yet mean direct rule from Beijing, short-circuiting the “one country, two systems” formula. “No one is in a position to dictate to the Chinese people,” Xi proclaimed last December. “The party is everything.”

Facebook Twitter

Pinterest

The ruins of the Summer Palace at Yuanmingyuan park in Beijing. Photograph: Adrian Bradshaw/EPA

It’s not all China’s fault. Deep-rooted anger at Britain has its origins in events largely forgotten in London but not in Beijing. It is true, as China says, that postwar colonial Britain showed scant regard for Hong Kong residents’ rights. This indifference was consistent with earlier humiliations heaped on the ruling Qing dynasty by Victorian imperialists – the cause of China’s “lost century”, concluding in 1945.

The first Anglo-Chinese opium war, from 1839-42, was supposedly a response to Chinese insults to Britain’s national honour. In truth it was mostly about money and power, about imposing free trade, and about securing a lucrative market for opium exports from British India, regardless of the human cost.

This destabilising intervention opened the gates to other foreign invaders and to decades of revolts, such as the Taiping rebellion, when up to 100 million people may have died. It also foreshadowed an infamous act of cultural vandalism, the burning and looting by British and French forces of the emperor’s wondrous Summer Palace in Beijing in 1860. Its Chinese name was Yuanmingyuan – “garden of perfect brightness”. And it was utterly destroyed. All Chinese schoolchildren are taught this.

Hunt deplored Beijing’s trashing of the 1984 Sino-British joint declaration, calling it an affront to the international rules-based order from which China benefits. But such righteous outrage comes awkwardly from a country that waged war in Iraq without legal authority and stays on friendly terms with murderers in Saudi Arabia. It ignores the lawless history of the pre-1914 “unequal treaties”.

Ironically, these old injustices were instrumental in shaping the Chinese communists’ 20th-century anti-imperialist, nationalist ideology – and the party’s insistence on regaining sovereignty over “lost” territories such as Hong Kong, Macau and, prospectively, Taiwan. As was often the case during its empire-building days, Britain sowed the seeds of its ultimate displacement.

China’s disdain, bordering on contempt, for Britain’s warnings stems not only from London’s past hypocrisy and historical amnesia, but also from a keen assessment of its current, palpable weakness. Given the gaping power imbalance, Hunt’s threat of unspecified “severe consequences” is all but meaningless.

The reality is chastening. Britain will need a post-Brexit trade deal. It needs Chinese investment, technological expertise, and even Huawei (if the US allows). But China does not really need Britain. Acting alone from a position of relative dependency, Britain cannot by itself change China’s behaviour or effectively promote its own values. That requires the sort of leverage only strong alliances bring. And since Donald Trump cannot be trusted, that means a united European front.

But Europe is being recklessly shunted aside. Even as he claims Britain is still a country with “global reach”, Hunt (like Boris Johnson) is undermining British international leadership and influence.

China’s scorn is well deserved. Democracy in Hong Kong is set to become Brexit’s first big overseas casualty.

英媒:中英实力悬殊 中国理所应当鄙视英国

2019年07月09日 07:25 环球时报

7,814

原标题:英媒:中国理所应当鄙视英国。

本文译自英国《卫报》7月6日文章,原题:中国看英国,只看到虚弱和虚伪

香港暴力事件引发英国与中国爆发口水战。令人不安的是,此事也凸显在一个强敌如林的世界里,未来脱欧后的英国显得孤立无援、虚弱无力。它还暴露所有西方民主国家与北京打交道时的一个难题:什么才是最重要的——自由价值还是赚钱发财?

中国驻英大使要求英国“勿插手香港事务”,把外交大臣亨特公开支持抗议者解读为支持暴力。另一名中方官员指责亨特“似乎还沉浸在昔日英国殖民者的幻象当中”。中方表示,英国暗中煽动骚乱是制造动荡的更大阴谋的一部分。与此同时,英国被嘲笑为一个虚弱、失败的国家,连自己国内问题都管不好。

中国对英国这种根深蒂固的愤怒,源自在伦敦基本被忘记、而在北京却没忘记的过去。正如中方所言,战后殖民主义国家英国对香港居民的权利毫无尊重可言。这种漠视与早先维多利亚时代的帝国主义者对清王朝所施加的屈辱——也是中国“失落的世纪”的起因——是一脉相承的。

亨特抨击北京背弃《中英联合声明》,称中国冒犯了自己从中获益的基于规则的国际秩序。然而,如此“义正辞严”的话语出自一个没有合法授权就在伊拉克进行战争的国家,不免显得尴尬。它还忽视了19世纪欧洲列强对华“不平等条约”那段无法无天的历史。昔日的不平等影响了中国20世纪反帝国主义的民族主义意识形态——以及收复对“失去”领土的主权的坚持。

对于英国的警告,中国不屑甚至近乎蔑视。这不仅是基于伦敦过去的虚伪和历史健忘症,而且是中国对于英国目前明显弱势的敏锐评估。鉴于中英两国实力悬殊,亨特的“将会有严重后果”之威胁几乎毫无意义。

现实是惨痛的。英国脱欧后需要贸易协议,需要中国的投资、中国的技术甚至华为(如果美国能允许的话)。而中国并不真正需要英国。英国相对依赖中国,单独采取行动,根本改变不了中方的行为或有效促进自身价值。这需要某种只有强大同盟才能带来的筹码。由于特朗普不可信任,这就意味着需要欧洲统一战线。但如今,欧洲被(英国)鲁莽地晾在一边。亨特说英国仍是一个具有“全球影响力”的国家,但其所作所为却在削弱英国的国际领导地位和影响力。中国理所应当鄙视英国。

British media: China and Britain's strength gap China should despise Britain

July 09, 2019 07:25 Global Times

7,814

Original title: British media: China should despise Britain.

This article is translated from the British "Guardian" July 6 article, the original title: China to see the UK, only see weakness and hypocrisy

The violence in Hong Kong triggered a war of words between Britain and China. What is disturbing is that this matter is also highlighted in a world of strong enemies such as Lin. After the Brexit, the United Kingdom seems to be helpless and weak. It also reveals a problem when all Western democracies deal with Beijing: What is the most important – free value or money to make money?

The Chinese ambassador to the United Kingdom asked the United Kingdom to "do not intervene in Hong Kong affairs" and to interpret the protesters as support for violence by Foreign Minister Hunter. Another Chinese official accused Hunter of "seemingly still immersed in the illusion of the former British colonists." The Chinese side said that the British secretly inciting riots is part of a larger conspiracy to create turmoil. At the same time, Britain was ridiculed as a weak, failed country, and even its own domestic problems were not well managed.

China’s deep-rooted anger against Britain stems from the past that was largely forgotten in London but not forgotten in Beijing. As the Chinese have said, the post-war colonialist country has no respect for the rights of Hong Kong residents. This indifference and the humiliation exerted by the earlier Victorian imperialists on the Qing Dynasty, which is also the cause of China's "lost century", is in the same vein.

Hunter slammed Beijing for abandoning the Sino-British Joint Declaration, saying that China offended the rule-based international order that it benefited from. However, such a "righteousness and resignation" discourse comes from a country that has not legally authorized to wage war in Iraq. It also ignores the lawless history of the “unequal treaties” of European powers in China in the 19th century. The inequality of the past has affected China’s anti-imperialist nationalist ideology in the 20th century – and the reinstatement of its sovereignty over “lost” territories.

For the British warning, China disdains and even scorns. This is not only based on London's past hypocrisy and historical amnesia, but also a keen assessment of China's current apparent weakness. Given the disparity in power between China and the UK, Hunter’s threat of “will have serious consequences” is almost meaningless.

The reality is bitter. The UK needs a trade agreement after Brexit and needs Chinese investment, Chinese technology and even Huawei (if the US can allow it). And China does not really need the UK. The United Kingdom is relatively dependent on China and acts alone. It cannot fundamentally change the behavior of China or effectively promote its own value. This requires some kind of chip that only a strong alliance can bring. Since Trump is untrustworthy, this means the need for a European united front. But now, Europe is being ruined by the (UK). Hunt said that Britain is still a country with "global influence", but its actions are weakening Britain's international leadership and influence. China should despise Britain.

https://www.theguardian.com/comment...ng-kong-jeremy-hunt-britain-rules-waves-wrong

Someone, please tell Jeremy Hunt: Britain no longer rules the waves

Simon Jenkins

He prefers to inflate his Tory leadership chances than face the truth about Britain’s lack of influence in Hong Kong

Thu 4 Jul 2019 17.07 BST Last modified on Fri 5 Jul 2019 09.52 BST

Shares

574

Comments

560

‘Britain left with a certain dignity’: the royal yacht Britannia sails into Hong Kong harbour on 23 June 1997. Photograph: Anthony Wallace/AFP/Getty Images

It was June 1997 and I was standing in the crowd on Hong Kong’s waterfront in torrential rain. A sad bugle played as the flag was lowered, and the royal yacht Britannia carried the Prince of Wales out to sea – and Britain out of its last Asian colony. We all had one thought. Thank goodness that’s over. Hong Kong’s last governor, Chris Patten, left what China clearly saw as a mess on the carpet, an elected assembly under the slogan “one country, two systems”. No one expected it to last, but Britain left with a certain dignity.

So why did Britain’s foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, take it on himself this week to revisit the scene? He applauded Hong Kong’s recent demonstrations and warned Beijing not to crack down on the rioters. He said the Chinese regime should not use a few broken windows as “a pretext for repression”. Britain would not stand for it. He said there would be “serious consequences”.

As was glaringly obvious, Hunt’s remarks had nothing to do with Hong Kong. He was puffing up his chest and signalling virtue in his contest for Downing Street with Boris Johnson. He wanted to show himself a player who could talk big on the world stage, who could move mountains. Johnson, he implied, could only move a few London cycle lanes.

China’s ambassador in London, Liu Xiaoming, might well have let this childishness pass, but he could not resist a crushing rejoinder. He said the issue was not the freedom of Hong Kong’s citizens to protest, which has been much tolerated over recent weeks. The issue was violence and vandalism against a democratic assembly. That was a crime. London should understand that, under Britain’s much-vaunted legacy, Hong Kong’s elected government and judiciary were responsible for crime, not Beijing.

Facebook Twitter

Jeremy Hunt: ‘He was puffing up his chest and signalling virtue in his contest for Downing Street.’ Photograph: Pool/Reuters

Liu pointed out that Hong Kong had enjoyed more democratic self-government under the shadow of Beijing than it had in a century and a half of British rule. Under Britain “there was no freedom, no democracy whatever” nor the right “to have an independent judicial power”. Hunt’s “gross and unacceptable” remarks offended the guiding principles of “mutual respect and non-interference in internal affairs”, long espoused by both countries. A spokesman in Beijing went further. Britain was hypocritical. He implied that it should sort out Brexit and leave Hong Kong to mend its own windows. The Foreign Office summoned the ambassador and told him not to be so rude – or once again there would be “serious consequences”.

The 1984 and 1994 bilateral accords on Hong Kong’s future were diplomatic triumphs of post-colonial history. Compromises were reached between diametrically opposed positions. China conceded the colony half a century of democracy to 2047, largely in return for a quiet life and a useful business outlet. As a result, a partial autonomy survived in the territory even during periods of repression elsewhere in China.

Anyone who now visits Hong Kong is aware of the fragility of this settlement. The presence on Chinese soil of a measure of alien democracy and human rights hangs by a thread. Recent street protests against the brutal extradition law were impressive and, so far, successful. The weekend’s descent into violence was trivial but, to a hypersensitive Beijing, alarming. The demonstrators provocative unfurling of the old British flag played into the hands of the Chinese hard-liners.

1:40

How Hong Kong protesters used hand signals and human chains to storm government – video explainer

The reality has always been that the 1984 deal depended on Beijing sticking to it; and that in turn will depend on how far the activists in Hong Kong push their luck. Beijing has already toppled three Hong Kong chief executives, and dares not lose effective control. The one certainty is that what happens between now and 2047 will be the outcome of a resolution of forces within China’s shifting elites, and nowhere else.

It is therefore hard to imagine a more blundering, cliched and counterproductive intervention than Hunt’s. The idea that Beijing would shift its policy one inch because someone halfway round the world was frantic to advance his career is farcical. As for Britain offering any practical aid or comfort to the street protesters, that is preposterous if not a cruel deception. What does Hunt mean by serious consequences? Will he send an aircraft carrier?

Jeremy Hunt refuses to rule out sanctions against China

Read more

The ritual of British ministers “raising human rights issues” with Beijing has long been a charade. The post-2008, pre-2012 Olympics talks – with London begging advice while criticising human rights abuses – was embarrassing to all concerned. The same went for David Cameron and George Osborne’s bizarre “kowtow diplomacy” in 2015, seeking funds for such vanity projects as Hinkley Point, HS2 and the “northern powerhouse”. It just gave China leverage over chunks of British infrastructure.

Hunt is currently championing hard Brexit on the basis that vast riches lie in bilateral deals “with the rest of the world”. If so, is he really going to embargo Chinese trade as a consequence of Hong Kong? He should watch out that Beijing does not return the compliment.

As Hunt walks to his Foreign Office chamber, he passes majestic paintings and sculptures celebrating the wonders that British imperial rule brought to the four corners of the Earth. It is tempting for his head to be turned by the voluptuous symbols of British power projection. It has clearly happened. Damn it, say the pictures, we used to rule the world.

Like Tony Blair, Hunt aches to blunder about the world declaring all its evils “unacceptable” and arguing “something must be done” about them. He wants his office to “punch above its weight”. Hong Kong is not his country and not his business. Britain handed it back to China two decades ago, surrendering sovereignty over it to an immeasurably greater power. Yet for people like Hunt it seems the imperial urge will never ease.

• Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/06/china-britain-weakness-hypocrisy-jeremy-hunt-hong-kong

China looks at Britain and sees only weakness and hypocrisy

Simon Tisdall

Jeremy Hunt’s support for the Hong Kong protests has released old resentments long suppressed

Sat 6 Jul 2019 14.00 BST Last modified on Sat 6 Jul 2019 23.00 BST

Shares

1,181

President Xi Jinping at a meeting in Beijing. Photograph: Huang Jingwen/Xinhua/Barcroft Media

Last week’s sudden outbreak of verbal hostilities with China, triggered by violent clashes in Hong Kong, provided a disturbing glimpse of post-Brexit Britain’s isolated and impotent future in a world of more muscular adversaries. It also underlined a dilemma facing all the western democracies in their dealings with Beijing: what matters most – liberal values or money-making?

Like bullies sensing weakness, Chinese officials let rip after Britain dared defend the demonstrators’ right to protest against the erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms. The row released tensions largely suppressed since the former colony was handed back in 1997. The depth of China’s pent-up fury was cautionary.

Liu Xiaoming, China’s ambassador, led the charge, demanding Britain keep its “hands off Hong Kong”. Liu misrepresented the foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt’s public support for the protesters as implying support for violence. Another official was personally insulting, accusing Hunt of “basking in the faded glory of British colonialism”.

Guardian Today: the headlines, the analysis, the debate - sent direct to you

Read more

China’s claim that Britain was surreptitiously fomenting unrest as part of a wider destabilisation conspiracy was classic Communist party propaganda-cum-paranoia. At the same time, Britain was mocked as an enfeebled, failing country, unable to manage its own internal problems. The obvious contradiction did not inhibit the rhetoric.

These broadsides, intended to demonstrate proud resilience, spoke instead of abiding insecurity. Xi Jinping, China’s “strongman” leader and de facto president-for-life, is said to have been deeply influenced by the east European revolutions of 1989 and the subsequent implosion of the Soviet Union.

Xi fears one-party China could go the same way. “Why did the Soviet Communist party collapse?” Xi asked in 2013 when discussing the risks posed by popular insurrections. One reason, he said, was that “nobody was a real man”. That tough-guy Xi is determined not to repeat Mikhail Gorbachev’s supposed mistakes is already abundantly clear.

His time in power since 2012 has been marked by expanding state control, a Mao-style personality cult reinforced by purges of party rivals (dressed up as anti-corruption drives), mass detentions and human rights abuses, pervasive censorship and an aggressive foreign policy signalling China’s ambitions as a global superpower.

Hong Kong’s demand for democratic self-determination directly contradicts Xi’s vision of the unchallengeable power of the party and its “core leader”. It threatens his ascendancy. Worse, it could encourage copycat resistance in mainland China, where public discontent exacerbated by an economic slowdown is growing.

That means more Hong Kong arrests and jailings. It means a slow-motion stifling of dissent, whatever Britain may say. And despite Thursday’s limited offer of talks, it may yet mean direct rule from Beijing, short-circuiting the “one country, two systems” formula. “No one is in a position to dictate to the Chinese people,” Xi proclaimed last December. “The party is everything.”

Facebook Twitter

The ruins of the Summer Palace at Yuanmingyuan park in Beijing. Photograph: Adrian Bradshaw/EPA

It’s not all China’s fault. Deep-rooted anger at Britain has its origins in events largely forgotten in London but not in Beijing. It is true, as China says, that postwar colonial Britain showed scant regard for Hong Kong residents’ rights. This indifference was consistent with earlier humiliations heaped on the ruling Qing dynasty by Victorian imperialists – the cause of China’s “lost century”, concluding in 1945.

The first Anglo-Chinese opium war, from 1839-42, was supposedly a response to Chinese insults to Britain’s national honour. In truth it was mostly about money and power, about imposing free trade, and about securing a lucrative market for opium exports from British India, regardless of the human cost.

This destabilising intervention opened the gates to other foreign invaders and to decades of revolts, such as the Taiping rebellion, when up to 100 million people may have died. It also foreshadowed an infamous act of cultural vandalism, the burning and looting by British and French forces of the emperor’s wondrous Summer Palace in Beijing in 1860. Its Chinese name was Yuanmingyuan – “garden of perfect brightness”. And it was utterly destroyed. All Chinese schoolchildren are taught this.

Hunt deplored Beijing’s trashing of the 1984 Sino-British joint declaration, calling it an affront to the international rules-based order from which China benefits. But such righteous outrage comes awkwardly from a country that waged war in Iraq without legal authority and stays on friendly terms with murderers in Saudi Arabia. It ignores the lawless history of the pre-1914 “unequal treaties”.

Ironically, these old injustices were instrumental in shaping the Chinese communists’ 20th-century anti-imperialist, nationalist ideology – and the party’s insistence on regaining sovereignty over “lost” territories such as Hong Kong, Macau and, prospectively, Taiwan. As was often the case during its empire-building days, Britain sowed the seeds of its ultimate displacement.

China’s disdain, bordering on contempt, for Britain’s warnings stems not only from London’s past hypocrisy and historical amnesia, but also from a keen assessment of its current, palpable weakness. Given the gaping power imbalance, Hunt’s threat of unspecified “severe consequences” is all but meaningless.

The reality is chastening. Britain will need a post-Brexit trade deal. It needs Chinese investment, technological expertise, and even Huawei (if the US allows). But China does not really need Britain. Acting alone from a position of relative dependency, Britain cannot by itself change China’s behaviour or effectively promote its own values. That requires the sort of leverage only strong alliances bring. And since Donald Trump cannot be trusted, that means a united European front.

But Europe is being recklessly shunted aside. Even as he claims Britain is still a country with “global reach”, Hunt (like Boris Johnson) is undermining British international leadership and influence.

China’s scorn is well deserved. Democracy in Hong Kong is set to become Brexit’s first big overseas casualty.