S'pore girl, 9, punctured small intestine after swallowing 14 magnetic balls

Magnets are not toys.Irwan Shah |

A nine-year-old girl in Singapore became ill for two weeks after ingesting tiny magnetic balls that constricted and punctured her small intestine.

A visit to the doctor did not uncover what was wrong initially and she subsequently got sicker.

The magnetic balls were sold as a toy.

Vomited green substance

The girl vomited a green substance on May 9, 2022, and her parents brought her to the KK Women's and Children's Hospital.

The doctor there deduced that it was a viral infection and gave her antibiotics to consume, according to The Straits Times (ST).

However, the girl began vomiting again about one-and-a-half weeks later.

This time, she was taken to the Thomson Medical Centre around May 19.

By this time, she could not even stay upright and had to be wheeled in.

Her mother, 39, said her daughter was having trouble consuming liquids and had lost 3kg by then.

Finding the cause

Nidhu Jasm, a paediatric surgeon at Thomson Medical Centre, attended to the girl.

According to Nidhu, she asked what the girl ate, and the girl's reply was that she was unable to eat and was always vomiting.

The girl went through an ultrasound scan at first, but the result was inconclusive.

The surgeon could only see diluted bubbles.

"We didn't actually find the cause, because magnets can't be picked up on an ultrasound scan," Nidhu told Mothership.sg.

X-ray revealed cause

An X-ray scan was done and it revealed the cause: A total of 14 magnetic balls were found in the girl's small intestine.

Each ball measured between 3mm and 5mm in diameter.

"It was sticking right next to each other, so we knew they were magnets because only magnets do that," the surgeon explained.

Emergency surgery needed

The girl was subsequently prepped and sent for a four-hour emergency surgery to remove the magnetic balls.

"It's like porridge, and then there's metal inside it. It's very easy to pull it out and they all come together because they're stuck," Nidhu said about the surgery.

Two stretches of her small intestine, measuring 3.5cm and 6.5cm, were also cut out because it was irreversibly damaged.

Nidhu also explained that instead of following the route through the small intestine, the magnets took a "shortcut" and were stuck to one another from different parts of the intestine.

This caused a blockage that led the girl to vomit.

The strength of the magnets also caused a hole in the small intestine.

According to ST's report, Nidhu said the magnets squeezing together will blow a hole in the intestine and it usually takes a week to 10 days to manifest.

Fortunately, the girl was diagnosed in time.

She was put on a liquid diet during the first two days after surgery and was switched to a diet consisting of porridge from the third day onwards.

The girl recovered smoothly.

Magnetic balls are dangerous

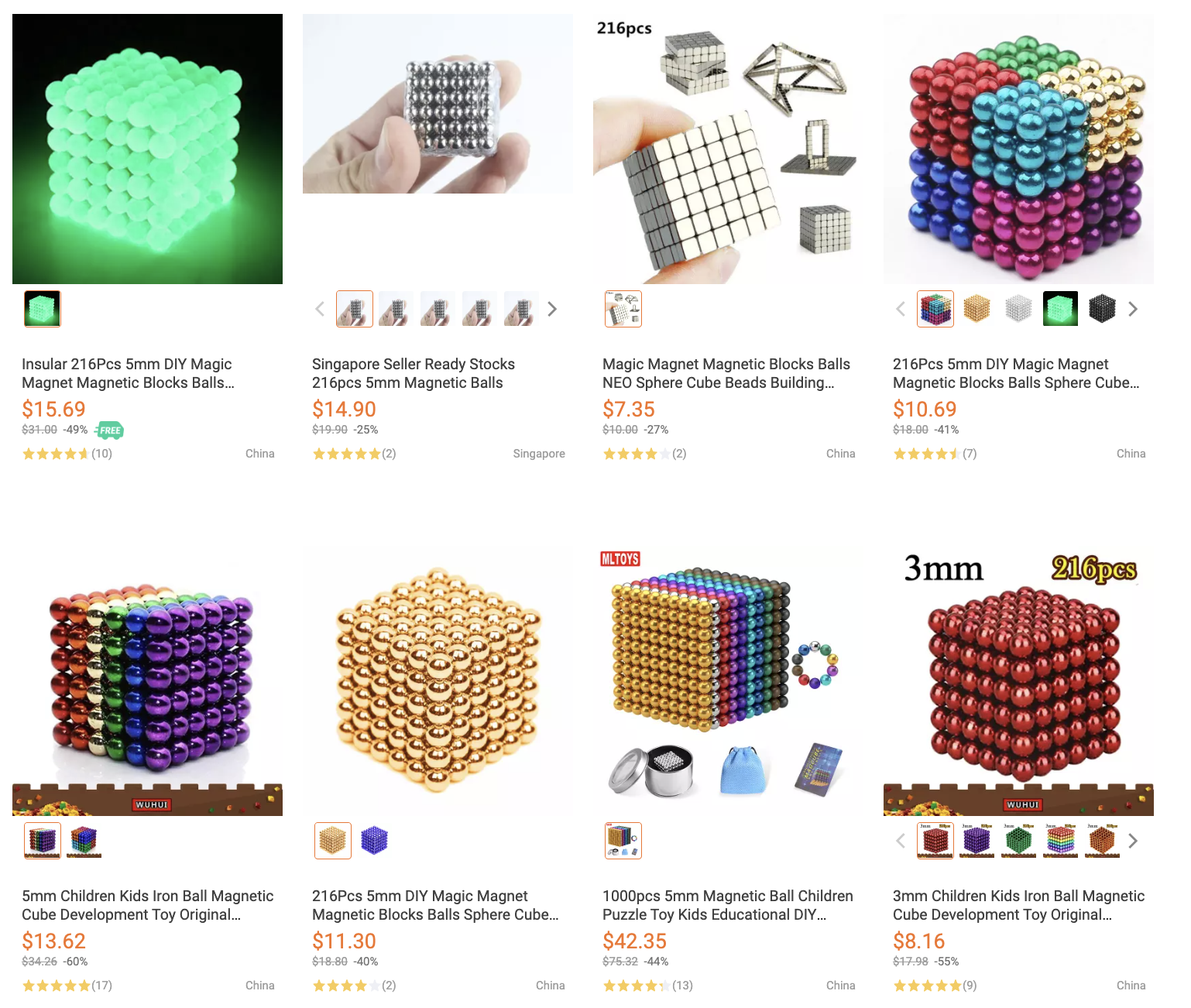

The girl's parents bought the toy, containing 216 magnetic balls, from the e-commerce site Lazada for S$17, ST reported.

They were persuaded by the girl to get it as she said her friends played with such toys too.

Nidhu elaborated that these magnetic toys are hazardous and dangerous when ingested.

A coin or a plastic toy will not stick to each other and will eventually be discarded naturally, said Nidhu.

However, magnets will get stuck along the way and requires surgery to get them out from the body.

Enterprise Singapore previously issued an advisory back in September 2019 about the dangers of such magnetic toys.

They can still be bought with relative ease from any e-commerce websites, such as Lazada or Shopee.

"Magnets are unique, they are not toys," stressed Naidhu.

She also told ST that the magnetic balls might go missing without any parent noticing and causing alarm, as there were hundreds of them.

The girl's parents threw the magnetic balls away following the ordeal.